User login

Managing a COVID-19–positive psychiatric patient on a medical unit

With the COVID-19 pandemic turning the world on its head, we have seen more first-episode psychotic breaks and quick deterioration in previously stable patients. Early in the pandemic, care was particularly complicated for psychiatric patients who had been infected with the virus. Many of these patients required immediate psychiatric hospitalization. At that time, many community hospital psychiatric inpatient units did not have the capacity, staffing, or infrastructure to safely admit such patients, so they needed to be managed on a medical unit. Here, I discuss the case of a COVID-19–positive woman with psychiatric illness who we managed while she was in quarantine on a medical unit.

Case report

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms. B, a 35-year-old teacher with a history of depression, was evaluated in the emergency department for bizarre behavior and paranoid delusions regarding her family. Initial laboratory and imaging testing was negative for any potential medical causes of her psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric hospitalization was recommended, but before Ms. B could be transferred to the psychiatric unit, she tested positive for COVID-19. At that time, our community hospital did not have a designated wing on our psychiatric unit for patients infected with COVID-19. Thus, Ms. B was admitted to the medical floor, where she was quarantined in her room. She would need to remain asymptomatic and test negative for COVID-19 before she could be transferred to the psychiatric unit.

Upon arriving at the medical unit, Ms. B was hostile and uncooperative. She frequently attempted to leave her room and required restraints throughout the day. Our consultation-liaison (CL) team was consulted to assist in managing her. During the initial interview, we noticed that she had covered all 4 walls of her room with papers filled with handwritten notes. Ms. B had cut her gown to expose her stomach and legs. She had pressured speech, tangential thinking, and was religiously preoccupied. She denied any visual and auditory hallucinations, but her persecutory delusions involving her family persisted. We believed that her signs and symptoms were consistent with a manic episode from underlying, and likely undiagnosed, bipolar I disorder that was precipitated by her COVID-19 infection.

We first addressed Ms. B’s and the staff’s safety by transferring her to a larger room with a vestibule at the end of the hallway so she had more room to walk and minimal exposure to the stimuli of the medical unit. We initiated one-on-one observation to redirect her and prevent elopement. We incentivized her cooperation with staff by providing her with paper, pencils, reading material, and phone privileges. We started oral risperidone 2 mg twice daily and lorazepam 2 mg 3 times daily for short-term behavioral control and acute treatment of her symptoms, with the goal of deferring additional treatment decisions to the inpatient psychiatry team after she was transferred to the psychiatric unit. Ms. B’s agitation and impulsivity improved. She began participating with the medical team and was eventually transferred out of our medical unit to a psychiatric unit at a different facility.

COVID-19 and psychiatric illness: Clinical concerns

While infection from COVID-19 and widespread social distancing of the general population have been linked to depression and anxiety, manic and psychotic symptoms secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic have not been well described. The association between influenza infection and psychosis has been reported since the Spanish Flu pandemic,1 but there is limited data on the association between COVID-19 and psychosis. A review of 14 studies found that 0.9% to 4% of people exposed to a virus during an epidemic or pandemic develop psychosis or psychotic symptoms.1 Psychosis was associated with viral exposure, treatments used to manage the infection (steroid therapy), and psychosocial stress. This study also found that treatment with low doses of antipsychotic medication—notably aripiprazole—seemed to have been effective.1

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind a thorough differential diagnosis and rule out any potential organic etiologies in a COVID-19–positive patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms.2 For Ms. B, we began by ruling out drug-induced psychosis and electrolyte imbalance, and obtained brain imaging to rule out malignancy. We considered an interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy, a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by alterations in sexual behavior, religiosity, and extensive and compulsive writing and drawing.3 Neurology was consulted to evaluate the patient and possibly use EEG to detect interictal spikes, a tall task given the patient’s restlessness and paranoia. Ultimately, we determined the patient was most likely exhibiting symptoms of previously undetected bipolar disorder.

Managing patients with psychiatric illness on a medical floor during a pandemic such as COVID-19 requires the psychiatrist to truly serve as a consultant and liaison between the patient and the treatment team.4 Clinical management should address both infection control and psychiatric symptoms.5 We visited with Ms. B frequently, provided psychoeducation, engaged her in treatment, and updated her on the treatment plan.

As the medical world continues to adjust to treating patients during the pandemic, CL psychiatrists may be tasked with managing patients with acute psychiatric illness on the medical unit while they await transfer to a psychiatric unit. A creative, multifaceted, and team-based approach is key to ensure effective care and safety for all involved.

1. Brown E, Gray R, Lo Monaco S, et al. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: a rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.005

2. Byrne P. Managing the acute psychotic episode. BMJ. 2007;334(7595):686-692. doi:10.1136/bmj.39148.668160.80

3. Waxman SG, Geschwind N. The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(12):1580-1586. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760300118011

4. Stern TA, Freudenreich O, Smith FA, et al. Psychotic patients. In: Massachusetts General Hospital: Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. Mosby; 1997:109-121.

5. Deshpande S, Livingstone A. First-onset psychosis in older adults: social isolation influence during COVID pandemic—a UK case series. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 2021;25(1):14-18. doi:10.1002/pnp.692

With the COVID-19 pandemic turning the world on its head, we have seen more first-episode psychotic breaks and quick deterioration in previously stable patients. Early in the pandemic, care was particularly complicated for psychiatric patients who had been infected with the virus. Many of these patients required immediate psychiatric hospitalization. At that time, many community hospital psychiatric inpatient units did not have the capacity, staffing, or infrastructure to safely admit such patients, so they needed to be managed on a medical unit. Here, I discuss the case of a COVID-19–positive woman with psychiatric illness who we managed while she was in quarantine on a medical unit.

Case report

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms. B, a 35-year-old teacher with a history of depression, was evaluated in the emergency department for bizarre behavior and paranoid delusions regarding her family. Initial laboratory and imaging testing was negative for any potential medical causes of her psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric hospitalization was recommended, but before Ms. B could be transferred to the psychiatric unit, she tested positive for COVID-19. At that time, our community hospital did not have a designated wing on our psychiatric unit for patients infected with COVID-19. Thus, Ms. B was admitted to the medical floor, where she was quarantined in her room. She would need to remain asymptomatic and test negative for COVID-19 before she could be transferred to the psychiatric unit.

Upon arriving at the medical unit, Ms. B was hostile and uncooperative. She frequently attempted to leave her room and required restraints throughout the day. Our consultation-liaison (CL) team was consulted to assist in managing her. During the initial interview, we noticed that she had covered all 4 walls of her room with papers filled with handwritten notes. Ms. B had cut her gown to expose her stomach and legs. She had pressured speech, tangential thinking, and was religiously preoccupied. She denied any visual and auditory hallucinations, but her persecutory delusions involving her family persisted. We believed that her signs and symptoms were consistent with a manic episode from underlying, and likely undiagnosed, bipolar I disorder that was precipitated by her COVID-19 infection.

We first addressed Ms. B’s and the staff’s safety by transferring her to a larger room with a vestibule at the end of the hallway so she had more room to walk and minimal exposure to the stimuli of the medical unit. We initiated one-on-one observation to redirect her and prevent elopement. We incentivized her cooperation with staff by providing her with paper, pencils, reading material, and phone privileges. We started oral risperidone 2 mg twice daily and lorazepam 2 mg 3 times daily for short-term behavioral control and acute treatment of her symptoms, with the goal of deferring additional treatment decisions to the inpatient psychiatry team after she was transferred to the psychiatric unit. Ms. B’s agitation and impulsivity improved. She began participating with the medical team and was eventually transferred out of our medical unit to a psychiatric unit at a different facility.

COVID-19 and psychiatric illness: Clinical concerns

While infection from COVID-19 and widespread social distancing of the general population have been linked to depression and anxiety, manic and psychotic symptoms secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic have not been well described. The association between influenza infection and psychosis has been reported since the Spanish Flu pandemic,1 but there is limited data on the association between COVID-19 and psychosis. A review of 14 studies found that 0.9% to 4% of people exposed to a virus during an epidemic or pandemic develop psychosis or psychotic symptoms.1 Psychosis was associated with viral exposure, treatments used to manage the infection (steroid therapy), and psychosocial stress. This study also found that treatment with low doses of antipsychotic medication—notably aripiprazole—seemed to have been effective.1

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind a thorough differential diagnosis and rule out any potential organic etiologies in a COVID-19–positive patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms.2 For Ms. B, we began by ruling out drug-induced psychosis and electrolyte imbalance, and obtained brain imaging to rule out malignancy. We considered an interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy, a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by alterations in sexual behavior, religiosity, and extensive and compulsive writing and drawing.3 Neurology was consulted to evaluate the patient and possibly use EEG to detect interictal spikes, a tall task given the patient’s restlessness and paranoia. Ultimately, we determined the patient was most likely exhibiting symptoms of previously undetected bipolar disorder.

Managing patients with psychiatric illness on a medical floor during a pandemic such as COVID-19 requires the psychiatrist to truly serve as a consultant and liaison between the patient and the treatment team.4 Clinical management should address both infection control and psychiatric symptoms.5 We visited with Ms. B frequently, provided psychoeducation, engaged her in treatment, and updated her on the treatment plan.

As the medical world continues to adjust to treating patients during the pandemic, CL psychiatrists may be tasked with managing patients with acute psychiatric illness on the medical unit while they await transfer to a psychiatric unit. A creative, multifaceted, and team-based approach is key to ensure effective care and safety for all involved.

With the COVID-19 pandemic turning the world on its head, we have seen more first-episode psychotic breaks and quick deterioration in previously stable patients. Early in the pandemic, care was particularly complicated for psychiatric patients who had been infected with the virus. Many of these patients required immediate psychiatric hospitalization. At that time, many community hospital psychiatric inpatient units did not have the capacity, staffing, or infrastructure to safely admit such patients, so they needed to be managed on a medical unit. Here, I discuss the case of a COVID-19–positive woman with psychiatric illness who we managed while she was in quarantine on a medical unit.

Case report

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Ms. B, a 35-year-old teacher with a history of depression, was evaluated in the emergency department for bizarre behavior and paranoid delusions regarding her family. Initial laboratory and imaging testing was negative for any potential medical causes of her psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric hospitalization was recommended, but before Ms. B could be transferred to the psychiatric unit, she tested positive for COVID-19. At that time, our community hospital did not have a designated wing on our psychiatric unit for patients infected with COVID-19. Thus, Ms. B was admitted to the medical floor, where she was quarantined in her room. She would need to remain asymptomatic and test negative for COVID-19 before she could be transferred to the psychiatric unit.

Upon arriving at the medical unit, Ms. B was hostile and uncooperative. She frequently attempted to leave her room and required restraints throughout the day. Our consultation-liaison (CL) team was consulted to assist in managing her. During the initial interview, we noticed that she had covered all 4 walls of her room with papers filled with handwritten notes. Ms. B had cut her gown to expose her stomach and legs. She had pressured speech, tangential thinking, and was religiously preoccupied. She denied any visual and auditory hallucinations, but her persecutory delusions involving her family persisted. We believed that her signs and symptoms were consistent with a manic episode from underlying, and likely undiagnosed, bipolar I disorder that was precipitated by her COVID-19 infection.

We first addressed Ms. B’s and the staff’s safety by transferring her to a larger room with a vestibule at the end of the hallway so she had more room to walk and minimal exposure to the stimuli of the medical unit. We initiated one-on-one observation to redirect her and prevent elopement. We incentivized her cooperation with staff by providing her with paper, pencils, reading material, and phone privileges. We started oral risperidone 2 mg twice daily and lorazepam 2 mg 3 times daily for short-term behavioral control and acute treatment of her symptoms, with the goal of deferring additional treatment decisions to the inpatient psychiatry team after she was transferred to the psychiatric unit. Ms. B’s agitation and impulsivity improved. She began participating with the medical team and was eventually transferred out of our medical unit to a psychiatric unit at a different facility.

COVID-19 and psychiatric illness: Clinical concerns

While infection from COVID-19 and widespread social distancing of the general population have been linked to depression and anxiety, manic and psychotic symptoms secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic have not been well described. The association between influenza infection and psychosis has been reported since the Spanish Flu pandemic,1 but there is limited data on the association between COVID-19 and psychosis. A review of 14 studies found that 0.9% to 4% of people exposed to a virus during an epidemic or pandemic develop psychosis or psychotic symptoms.1 Psychosis was associated with viral exposure, treatments used to manage the infection (steroid therapy), and psychosocial stress. This study also found that treatment with low doses of antipsychotic medication—notably aripiprazole—seemed to have been effective.1

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind a thorough differential diagnosis and rule out any potential organic etiologies in a COVID-19–positive patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms.2 For Ms. B, we began by ruling out drug-induced psychosis and electrolyte imbalance, and obtained brain imaging to rule out malignancy. We considered an interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy, a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by alterations in sexual behavior, religiosity, and extensive and compulsive writing and drawing.3 Neurology was consulted to evaluate the patient and possibly use EEG to detect interictal spikes, a tall task given the patient’s restlessness and paranoia. Ultimately, we determined the patient was most likely exhibiting symptoms of previously undetected bipolar disorder.

Managing patients with psychiatric illness on a medical floor during a pandemic such as COVID-19 requires the psychiatrist to truly serve as a consultant and liaison between the patient and the treatment team.4 Clinical management should address both infection control and psychiatric symptoms.5 We visited with Ms. B frequently, provided psychoeducation, engaged her in treatment, and updated her on the treatment plan.

As the medical world continues to adjust to treating patients during the pandemic, CL psychiatrists may be tasked with managing patients with acute psychiatric illness on the medical unit while they await transfer to a psychiatric unit. A creative, multifaceted, and team-based approach is key to ensure effective care and safety for all involved.

1. Brown E, Gray R, Lo Monaco S, et al. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: a rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.005

2. Byrne P. Managing the acute psychotic episode. BMJ. 2007;334(7595):686-692. doi:10.1136/bmj.39148.668160.80

3. Waxman SG, Geschwind N. The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(12):1580-1586. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760300118011

4. Stern TA, Freudenreich O, Smith FA, et al. Psychotic patients. In: Massachusetts General Hospital: Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. Mosby; 1997:109-121.

5. Deshpande S, Livingstone A. First-onset psychosis in older adults: social isolation influence during COVID pandemic—a UK case series. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 2021;25(1):14-18. doi:10.1002/pnp.692

1. Brown E, Gray R, Lo Monaco S, et al. The potential impact of COVID-19 on psychosis: a rapid review of contemporary epidemic and pandemic research. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:79-87. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.005

2. Byrne P. Managing the acute psychotic episode. BMJ. 2007;334(7595):686-692. doi:10.1136/bmj.39148.668160.80

3. Waxman SG, Geschwind N. The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(12):1580-1586. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760300118011

4. Stern TA, Freudenreich O, Smith FA, et al. Psychotic patients. In: Massachusetts General Hospital: Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. Mosby; 1997:109-121.

5. Deshpande S, Livingstone A. First-onset psychosis in older adults: social isolation influence during COVID pandemic—a UK case series. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 2021;25(1):14-18. doi:10.1002/pnp.692

Celebrating our colleagues

several of whom I am privileged to work with on a daily basis. We also welcome the newest members of AGA’s Governing Board, Maria T. Abreu, MD, AGAF, who is an outstanding leader and representative of a much larger group of volunteer members who work tirelessly to advance AGA’s initiatives to enhance the clinical practice of gastroenterology and improve patient outcomes. The nominating committee also appointed the following slate of councilors, which is subject to membership vote: Kim Barrett, PhD, AGAF; Lawrence Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF; and Sheryl Pfeil, MD, AGAF.

This month’s issue also highlights two newly-developed clinical risk-prediction tools – one designed to assist clinicians in predicting alcoholic hepatitis mortality, and another designed to identify inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients at high-risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE) post-hospitalization. While no prediction model is perfect, these tools can positively impact clinical decision-making and contribute to improved patient outcomes. We also include recommendations on managing IBD in older patients, and report on a study suggesting an increase in late-stage cancer diagnoses in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. AGA’s new clinical guideline on systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and Clinical Practice Update on non-invasive colorectal cancer screening also are featured. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox, Dr. Feuerstein, Dr. Sofia, Dr. Guha, and Dr. Streett offer timely recommendations regarding how to overcome existing barriers to achieve high-value IBD care.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

several of whom I am privileged to work with on a daily basis. We also welcome the newest members of AGA’s Governing Board, Maria T. Abreu, MD, AGAF, who is an outstanding leader and representative of a much larger group of volunteer members who work tirelessly to advance AGA’s initiatives to enhance the clinical practice of gastroenterology and improve patient outcomes. The nominating committee also appointed the following slate of councilors, which is subject to membership vote: Kim Barrett, PhD, AGAF; Lawrence Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF; and Sheryl Pfeil, MD, AGAF.

This month’s issue also highlights two newly-developed clinical risk-prediction tools – one designed to assist clinicians in predicting alcoholic hepatitis mortality, and another designed to identify inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients at high-risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE) post-hospitalization. While no prediction model is perfect, these tools can positively impact clinical decision-making and contribute to improved patient outcomes. We also include recommendations on managing IBD in older patients, and report on a study suggesting an increase in late-stage cancer diagnoses in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. AGA’s new clinical guideline on systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and Clinical Practice Update on non-invasive colorectal cancer screening also are featured. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox, Dr. Feuerstein, Dr. Sofia, Dr. Guha, and Dr. Streett offer timely recommendations regarding how to overcome existing barriers to achieve high-value IBD care.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

several of whom I am privileged to work with on a daily basis. We also welcome the newest members of AGA’s Governing Board, Maria T. Abreu, MD, AGAF, who is an outstanding leader and representative of a much larger group of volunteer members who work tirelessly to advance AGA’s initiatives to enhance the clinical practice of gastroenterology and improve patient outcomes. The nominating committee also appointed the following slate of councilors, which is subject to membership vote: Kim Barrett, PhD, AGAF; Lawrence Kosinski, MD, MBA, AGAF; and Sheryl Pfeil, MD, AGAF.

This month’s issue also highlights two newly-developed clinical risk-prediction tools – one designed to assist clinicians in predicting alcoholic hepatitis mortality, and another designed to identify inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients at high-risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE) post-hospitalization. While no prediction model is perfect, these tools can positively impact clinical decision-making and contribute to improved patient outcomes. We also include recommendations on managing IBD in older patients, and report on a study suggesting an increase in late-stage cancer diagnoses in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. AGA’s new clinical guideline on systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and Clinical Practice Update on non-invasive colorectal cancer screening also are featured. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox, Dr. Feuerstein, Dr. Sofia, Dr. Guha, and Dr. Streett offer timely recommendations regarding how to overcome existing barriers to achieve high-value IBD care.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

USPSTF issues draft guidance on statins for primary CVD prevention

On February 22, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) posted draft recommendations on the use of statins as a method of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 This is an update to their 2016 recommendations and reaffirms the guidance published at that time.

What’s recommended. The recommendations have 3 parts and are intended for adults with no evidence or previous diagnosis of CVD.

- Statins should be prescribed for those who meet 3 criteria: (1) are ages 40 through 75 years; (2) have 1 or more CVD risk factors (high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use); and (3) have a calculated 10-year risk of a CVD event of 10% or greater. (The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD Risk Calculator, recommended by the USPSTF, can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com/.) This is a “B” recommendation.1

- Selectively offer a statin, based on a discussion of benefits and risks and patient preferences, to those who meet criteria 1 and 2 above but who have a calculated CVD risk of 7.5% to 10%. This is a “C” recommendation.1

- For those ages 76 years and older, there is insufficient evidence to assess benefits and harms of statin use. The USPSTF therefore issued an “I” statement for this group.1

What to prescribe. The USPSTF feels that moderate-intensity statin therapy is a reasonable approach for most people who use statins for primary CVD prevention. This would equate to atorvastatin 10 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, or simvastatin 20 to 40 mg daily.1

A few notes on the evidence. Data from 22 studies were included in the evidence review upon which the recommendations are based. The mean duration of follow-up was 3 years. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 stroke was about 256; to prevent 1 myocardial infarction, 112; and to prevent all CVD events, 78.2

What others recommend. These recommendations are mostly consistent with those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, except that those organizations recommend initiating statins in all those with a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 7.5%.1

1. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Published February 22, 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

2. Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 219. AHRQ Publication No. 22-05291-EF-1. Published February 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

On February 22, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) posted draft recommendations on the use of statins as a method of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 This is an update to their 2016 recommendations and reaffirms the guidance published at that time.

What’s recommended. The recommendations have 3 parts and are intended for adults with no evidence or previous diagnosis of CVD.

- Statins should be prescribed for those who meet 3 criteria: (1) are ages 40 through 75 years; (2) have 1 or more CVD risk factors (high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use); and (3) have a calculated 10-year risk of a CVD event of 10% or greater. (The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD Risk Calculator, recommended by the USPSTF, can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com/.) This is a “B” recommendation.1

- Selectively offer a statin, based on a discussion of benefits and risks and patient preferences, to those who meet criteria 1 and 2 above but who have a calculated CVD risk of 7.5% to 10%. This is a “C” recommendation.1

- For those ages 76 years and older, there is insufficient evidence to assess benefits and harms of statin use. The USPSTF therefore issued an “I” statement for this group.1

What to prescribe. The USPSTF feels that moderate-intensity statin therapy is a reasonable approach for most people who use statins for primary CVD prevention. This would equate to atorvastatin 10 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, or simvastatin 20 to 40 mg daily.1

A few notes on the evidence. Data from 22 studies were included in the evidence review upon which the recommendations are based. The mean duration of follow-up was 3 years. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 stroke was about 256; to prevent 1 myocardial infarction, 112; and to prevent all CVD events, 78.2

What others recommend. These recommendations are mostly consistent with those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, except that those organizations recommend initiating statins in all those with a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 7.5%.1

On February 22, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) posted draft recommendations on the use of statins as a method of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 This is an update to their 2016 recommendations and reaffirms the guidance published at that time.

What’s recommended. The recommendations have 3 parts and are intended for adults with no evidence or previous diagnosis of CVD.

- Statins should be prescribed for those who meet 3 criteria: (1) are ages 40 through 75 years; (2) have 1 or more CVD risk factors (high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, diabetes, tobacco use); and (3) have a calculated 10-year risk of a CVD event of 10% or greater. (The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD Risk Calculator, recommended by the USPSTF, can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com/.) This is a “B” recommendation.1

- Selectively offer a statin, based on a discussion of benefits and risks and patient preferences, to those who meet criteria 1 and 2 above but who have a calculated CVD risk of 7.5% to 10%. This is a “C” recommendation.1

- For those ages 76 years and older, there is insufficient evidence to assess benefits and harms of statin use. The USPSTF therefore issued an “I” statement for this group.1

What to prescribe. The USPSTF feels that moderate-intensity statin therapy is a reasonable approach for most people who use statins for primary CVD prevention. This would equate to atorvastatin 10 mg, pravastatin 40 mg, or simvastatin 20 to 40 mg daily.1

A few notes on the evidence. Data from 22 studies were included in the evidence review upon which the recommendations are based. The mean duration of follow-up was 3 years. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 stroke was about 256; to prevent 1 myocardial infarction, 112; and to prevent all CVD events, 78.2

What others recommend. These recommendations are mostly consistent with those of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, except that those organizations recommend initiating statins in all those with a 10-year CVD risk ≥ 7.5%.1

1. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Published February 22, 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

2. Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 219. AHRQ Publication No. 22-05291-EF-1. Published February 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

1. USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: preventive medication. Published February 22, 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

2. Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 219. AHRQ Publication No. 22-05291-EF-1. Published February 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/draft-evidence-review/statin-use-primary-prevention-cardiovascular-disease-adults

Selecting Between CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Advanced HR+/HER2- Breast Cancer

Patients diagnosed with advanced hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (HER2-) breast cancer have significantly improved outcomes with the combination of a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor and endocrine therapy compared with endocrine therapy alone.

Dr Sara Hurvitz, director of the Breast Cancer Clinical Trials Program at UCLA, discusses the efficacy, tolerability, and patient quality-of-life factors to consider when deciding which of the three available CDK4/6 inhibitors — palbociclib, ribociclib, or abemaciclib — is appropriate for your patient in the frontline setting.

Reporting on data from the ongoing MONALEESA, MONARCH, and PALOMA trials, Dr Hurvitz spotlights the differences and similarities between agents that may help steer treatment decisions for pre- or perimenopausal patients

--

Associate Professor, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA; Medical Director, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Clinical Research Unit; Co-director, Santa Monica-UCLA Outpatient Oncology Practices; Director, Breast Cancer Clinical Trials Program, UCLA, Los Angeles, California

Sara A. Hurvitz, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Ambrx; Amgen; Arvinas; Bayer; BioMarin; Cascadian Therapeutics; Daiichi Sankyo; Dignitana; Genentech/Roche; Gilead Sciences; GlaxoSmithKline; Immunomedics; Lilly; MacroGenics; Merrimack; Novartis; OBI Pharma; Pfizer; Phoenix Molecular Designs; Pieris; Puma Biotechnology; Radius; Samumed; Sanofi; Seattle Genetics; Zymeworks

Has been reimbursed for travel, accommodations, or other expenses by Lilly

Patients diagnosed with advanced hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (HER2-) breast cancer have significantly improved outcomes with the combination of a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor and endocrine therapy compared with endocrine therapy alone.

Dr Sara Hurvitz, director of the Breast Cancer Clinical Trials Program at UCLA, discusses the efficacy, tolerability, and patient quality-of-life factors to consider when deciding which of the three available CDK4/6 inhibitors — palbociclib, ribociclib, or abemaciclib — is appropriate for your patient in the frontline setting.

Reporting on data from the ongoing MONALEESA, MONARCH, and PALOMA trials, Dr Hurvitz spotlights the differences and similarities between agents that may help steer treatment decisions for pre- or perimenopausal patients

--

Associate Professor, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA; Medical Director, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Clinical Research Unit; Co-director, Santa Monica-UCLA Outpatient Oncology Practices; Director, Breast Cancer Clinical Trials Program, UCLA, Los Angeles, California

Sara A. Hurvitz, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Ambrx; Amgen; Arvinas; Bayer; BioMarin; Cascadian Therapeutics; Daiichi Sankyo; Dignitana; Genentech/Roche; Gilead Sciences; GlaxoSmithKline; Immunomedics; Lilly; MacroGenics; Merrimack; Novartis; OBI Pharma; Pfizer; Phoenix Molecular Designs; Pieris; Puma Biotechnology; Radius; Samumed; Sanofi; Seattle Genetics; Zymeworks

Has been reimbursed for travel, accommodations, or other expenses by Lilly

Patients diagnosed with advanced hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (HER2-) breast cancer have significantly improved outcomes with the combination of a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor and endocrine therapy compared with endocrine therapy alone.

Dr Sara Hurvitz, director of the Breast Cancer Clinical Trials Program at UCLA, discusses the efficacy, tolerability, and patient quality-of-life factors to consider when deciding which of the three available CDK4/6 inhibitors — palbociclib, ribociclib, or abemaciclib — is appropriate for your patient in the frontline setting.

Reporting on data from the ongoing MONALEESA, MONARCH, and PALOMA trials, Dr Hurvitz spotlights the differences and similarities between agents that may help steer treatment decisions for pre- or perimenopausal patients

--

Associate Professor, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA; Medical Director, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Clinical Research Unit; Co-director, Santa Monica-UCLA Outpatient Oncology Practices; Director, Breast Cancer Clinical Trials Program, UCLA, Los Angeles, California

Sara A. Hurvitz, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Ambrx; Amgen; Arvinas; Bayer; BioMarin; Cascadian Therapeutics; Daiichi Sankyo; Dignitana; Genentech/Roche; Gilead Sciences; GlaxoSmithKline; Immunomedics; Lilly; MacroGenics; Merrimack; Novartis; OBI Pharma; Pfizer; Phoenix Molecular Designs; Pieris; Puma Biotechnology; Radius; Samumed; Sanofi; Seattle Genetics; Zymeworks

Has been reimbursed for travel, accommodations, or other expenses by Lilly

Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency: Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

What is your approach to differentiating EPI from other pancreatic conditions when making a diagnosis?

Dr. Kothari: Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, or EPI, is a condition largely defined by malabsorption as the result of inadequate digestive enzymes. The resulting symptoms from maldigestion include bloating, malodorous gas, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, and weight change. EPI can be caused by intrinsic pancreatic disorders (such as chronic pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis or pancreatic cancer) or from extra-pancreatic diseases (including the result of gastrointestinal surgery). Thus, EPI should be considered a consequence of an already existing gastrointestinal disorder.

Can you a speak a little bit more about the signs and symptoms or characteristics that are most common in patients with EPI?

Dr. Kothari: The symptoms of EPI can range from bloating and abdominal pain with mild to overt steatorrhea with greasy and oily stools that are difficult to flush with malodorous flatulence, weight loss, and symptoms of vitamin and micronutrient deficiency. The pathophysiology of these symptoms results from inadequate enzymes which are needed for digestion. Particularly, lipase is the major enzyme needed for fat digestion and thus when not present leads to fat maldigestion resulting in symptoms. Furthermore, undigested fats result in alterations in gut motility which can further exacerbate symptoms to include nausea, vomiting, early satiety and inadequate stool evacuation.

Patients who have fat malabsorption, particularly for pancreatic insufficiency, can also have malnutrition as a result of inadequate absorption of nutrients and micronutrients. Particularly, we think about fat-soluble vitamins-- vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin D, and vitamin K and in the initial evaluation of patients with established EPI, one could consider evaluation of comorbid bone disease.

How crucial is having the correct interpretation of the clinical presentation to pinpointing the diagnosis?

Dr. Kothari: This is a great question because, with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency as there is growing publicity for the disorder and because symptoms can be rather non-specific when mild, it is important to be informed on how best to make this diagnosis. Thus, it is important to review the predisposing conditions that may lead to the diagnosis of EPI. These conditions include cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis, previous pancreatic surgery, history of pancreatic cancer (or suspicion for new pancreatic cancer), history of diabetes, celiac disease, history of luminal surgeries (including bariatric surgery), and inflammatory bowel disease. Further, since EPI can be a result of intrinsic pancreatic pathologies, it is critical to consider the risk factors for chronic pancreatitis which include alcohol and tobacco ingestion, prior episodes of recurrent acute pancreatitis, genetic conditions that may predispose patients to chronic pancreatitis, including cystic fibrosis, and hereditary conditions that also result in pancreatitis. As clinicians, it is our role to obtain an accurate history to best gauge the risk factors for EPI.

After reviewing risk factors, we then must review the clinical presentation to know if the symptoms could be from EPI which include bloating, gas, abdominal pain, weight changes, changes in bowel habits and consequences of vitamin deficiencies. Since the symptoms of mild EPI can be similar to other GI conditions such as SIBO, celiac disease, and functional bowel disorders, gauging whether a patient has risk factors for EPI will help the clinician understand how likely a diagnosis of EPI may be and if and what testing would be appropriate.

In my practice, I consider diagnostic testing in patients who may be at risk for EPI and have mild symptoms such malodorous gas, bloating and mild steatorrhea. For patient with clear evidence of steatorrhea (weight loss and vitamin deficiencies) and have strong risk factors for EPI (i.e. heavy alcohol and tobacco and/or a history of recurrent or severe acute pancreatitis), I might consider imaging and/or empiric therapies as to expedite care.

How difficult is it to diagnose EPI and what steps do you take to ensure that you prescribe patients with the proper therapy?

Dr. Kothari: The diagnosis of pancreatic insufficiency, in my mind, needs to start with assessing the pre-test probability of the patient having EPI, since testing could lead to a false positive.

The test of choice in most scenarios for diagnosing pancreatic insufficiency is a stool test known as the fecal elastase. It is a measurement of pancreatic elastase in the stool. The test itself is a concentration. For any condition that results in a dilute stool sample, that'll result in a falsely low value that can give a patient a false positive test. Now, this can be corrected by the lab concentrating the stool sample before running the test, but that testing center needs to know how to do that.

The other assumption that we make with this stool test is that we assume that the elastase is a stable molecule that can traverse all the gut and be collected adequately. And for any reason, if that enzyme is degraded for any reason, it's also going to provide a low test, a low result, resulting in a false positive.

If they have risk factors for chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic disease and they're presenting with symptoms of EPI, then the usual test that I'll choose is dedicated pancreatic imaging such as an MRI or dedicated CT pancreatic imaging, or endoscopic ultrasound. If we clinch a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and they have symptoms of pancreatic insufficiency, I think that’s enough to presume a diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and start treatment.

On the other hand, in patients who do not have risk factors for pancreatic disease but there remains some clinical suspicion for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, then it may be reasonable to check a fecal elastase to rule out pancreatic insufficiency. If the test results are low, then follow-up dedicated pancreas imaging would be the next step in delineating intrinsic pancreatic conditions form extra-pancreatic causes. If pancreas imaging effectively rules out pancreatic disease then I consider checking for celiac disease, ruling out small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and considering assessment of luminal motility (either with a capsule or small bowel follow through). Although functional neuroendocrine tumors have been previously considered a cause of EPI, these tumors tend to present with secretory diarrhea which typically present differently (and often more dramatically) than other causes of EPI. Thus, I do not routinely check vasoactive hormone levels.

I think the American Gastroenterological Association has great patient education documents for our patients. Thus, I would encourage our colleagues to use the AGA for their resources for our patients on EPI.

What is your approach to differentiating EPI from other pancreatic conditions when making a diagnosis?

Dr. Kothari: Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, or EPI, is a condition largely defined by malabsorption as the result of inadequate digestive enzymes. The resulting symptoms from maldigestion include bloating, malodorous gas, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, and weight change. EPI can be caused by intrinsic pancreatic disorders (such as chronic pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis or pancreatic cancer) or from extra-pancreatic diseases (including the result of gastrointestinal surgery). Thus, EPI should be considered a consequence of an already existing gastrointestinal disorder.

Can you a speak a little bit more about the signs and symptoms or characteristics that are most common in patients with EPI?

Dr. Kothari: The symptoms of EPI can range from bloating and abdominal pain with mild to overt steatorrhea with greasy and oily stools that are difficult to flush with malodorous flatulence, weight loss, and symptoms of vitamin and micronutrient deficiency. The pathophysiology of these symptoms results from inadequate enzymes which are needed for digestion. Particularly, lipase is the major enzyme needed for fat digestion and thus when not present leads to fat maldigestion resulting in symptoms. Furthermore, undigested fats result in alterations in gut motility which can further exacerbate symptoms to include nausea, vomiting, early satiety and inadequate stool evacuation.

Patients who have fat malabsorption, particularly for pancreatic insufficiency, can also have malnutrition as a result of inadequate absorption of nutrients and micronutrients. Particularly, we think about fat-soluble vitamins-- vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin D, and vitamin K and in the initial evaluation of patients with established EPI, one could consider evaluation of comorbid bone disease.

How crucial is having the correct interpretation of the clinical presentation to pinpointing the diagnosis?

Dr. Kothari: This is a great question because, with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency as there is growing publicity for the disorder and because symptoms can be rather non-specific when mild, it is important to be informed on how best to make this diagnosis. Thus, it is important to review the predisposing conditions that may lead to the diagnosis of EPI. These conditions include cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis, previous pancreatic surgery, history of pancreatic cancer (or suspicion for new pancreatic cancer), history of diabetes, celiac disease, history of luminal surgeries (including bariatric surgery), and inflammatory bowel disease. Further, since EPI can be a result of intrinsic pancreatic pathologies, it is critical to consider the risk factors for chronic pancreatitis which include alcohol and tobacco ingestion, prior episodes of recurrent acute pancreatitis, genetic conditions that may predispose patients to chronic pancreatitis, including cystic fibrosis, and hereditary conditions that also result in pancreatitis. As clinicians, it is our role to obtain an accurate history to best gauge the risk factors for EPI.

After reviewing risk factors, we then must review the clinical presentation to know if the symptoms could be from EPI which include bloating, gas, abdominal pain, weight changes, changes in bowel habits and consequences of vitamin deficiencies. Since the symptoms of mild EPI can be similar to other GI conditions such as SIBO, celiac disease, and functional bowel disorders, gauging whether a patient has risk factors for EPI will help the clinician understand how likely a diagnosis of EPI may be and if and what testing would be appropriate.

In my practice, I consider diagnostic testing in patients who may be at risk for EPI and have mild symptoms such malodorous gas, bloating and mild steatorrhea. For patient with clear evidence of steatorrhea (weight loss and vitamin deficiencies) and have strong risk factors for EPI (i.e. heavy alcohol and tobacco and/or a history of recurrent or severe acute pancreatitis), I might consider imaging and/or empiric therapies as to expedite care.

How difficult is it to diagnose EPI and what steps do you take to ensure that you prescribe patients with the proper therapy?

Dr. Kothari: The diagnosis of pancreatic insufficiency, in my mind, needs to start with assessing the pre-test probability of the patient having EPI, since testing could lead to a false positive.

The test of choice in most scenarios for diagnosing pancreatic insufficiency is a stool test known as the fecal elastase. It is a measurement of pancreatic elastase in the stool. The test itself is a concentration. For any condition that results in a dilute stool sample, that'll result in a falsely low value that can give a patient a false positive test. Now, this can be corrected by the lab concentrating the stool sample before running the test, but that testing center needs to know how to do that.

The other assumption that we make with this stool test is that we assume that the elastase is a stable molecule that can traverse all the gut and be collected adequately. And for any reason, if that enzyme is degraded for any reason, it's also going to provide a low test, a low result, resulting in a false positive.

If they have risk factors for chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic disease and they're presenting with symptoms of EPI, then the usual test that I'll choose is dedicated pancreatic imaging such as an MRI or dedicated CT pancreatic imaging, or endoscopic ultrasound. If we clinch a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and they have symptoms of pancreatic insufficiency, I think that’s enough to presume a diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and start treatment.

On the other hand, in patients who do not have risk factors for pancreatic disease but there remains some clinical suspicion for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, then it may be reasonable to check a fecal elastase to rule out pancreatic insufficiency. If the test results are low, then follow-up dedicated pancreas imaging would be the next step in delineating intrinsic pancreatic conditions form extra-pancreatic causes. If pancreas imaging effectively rules out pancreatic disease then I consider checking for celiac disease, ruling out small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and considering assessment of luminal motility (either with a capsule or small bowel follow through). Although functional neuroendocrine tumors have been previously considered a cause of EPI, these tumors tend to present with secretory diarrhea which typically present differently (and often more dramatically) than other causes of EPI. Thus, I do not routinely check vasoactive hormone levels.

I think the American Gastroenterological Association has great patient education documents for our patients. Thus, I would encourage our colleagues to use the AGA for their resources for our patients on EPI.

What is your approach to differentiating EPI from other pancreatic conditions when making a diagnosis?

Dr. Kothari: Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, or EPI, is a condition largely defined by malabsorption as the result of inadequate digestive enzymes. The resulting symptoms from maldigestion include bloating, malodorous gas, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, and weight change. EPI can be caused by intrinsic pancreatic disorders (such as chronic pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis or pancreatic cancer) or from extra-pancreatic diseases (including the result of gastrointestinal surgery). Thus, EPI should be considered a consequence of an already existing gastrointestinal disorder.

Can you a speak a little bit more about the signs and symptoms or characteristics that are most common in patients with EPI?

Dr. Kothari: The symptoms of EPI can range from bloating and abdominal pain with mild to overt steatorrhea with greasy and oily stools that are difficult to flush with malodorous flatulence, weight loss, and symptoms of vitamin and micronutrient deficiency. The pathophysiology of these symptoms results from inadequate enzymes which are needed for digestion. Particularly, lipase is the major enzyme needed for fat digestion and thus when not present leads to fat maldigestion resulting in symptoms. Furthermore, undigested fats result in alterations in gut motility which can further exacerbate symptoms to include nausea, vomiting, early satiety and inadequate stool evacuation.

Patients who have fat malabsorption, particularly for pancreatic insufficiency, can also have malnutrition as a result of inadequate absorption of nutrients and micronutrients. Particularly, we think about fat-soluble vitamins-- vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin D, and vitamin K and in the initial evaluation of patients with established EPI, one could consider evaluation of comorbid bone disease.

How crucial is having the correct interpretation of the clinical presentation to pinpointing the diagnosis?

Dr. Kothari: This is a great question because, with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency as there is growing publicity for the disorder and because symptoms can be rather non-specific when mild, it is important to be informed on how best to make this diagnosis. Thus, it is important to review the predisposing conditions that may lead to the diagnosis of EPI. These conditions include cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, acute pancreatitis, previous pancreatic surgery, history of pancreatic cancer (or suspicion for new pancreatic cancer), history of diabetes, celiac disease, history of luminal surgeries (including bariatric surgery), and inflammatory bowel disease. Further, since EPI can be a result of intrinsic pancreatic pathologies, it is critical to consider the risk factors for chronic pancreatitis which include alcohol and tobacco ingestion, prior episodes of recurrent acute pancreatitis, genetic conditions that may predispose patients to chronic pancreatitis, including cystic fibrosis, and hereditary conditions that also result in pancreatitis. As clinicians, it is our role to obtain an accurate history to best gauge the risk factors for EPI.

After reviewing risk factors, we then must review the clinical presentation to know if the symptoms could be from EPI which include bloating, gas, abdominal pain, weight changes, changes in bowel habits and consequences of vitamin deficiencies. Since the symptoms of mild EPI can be similar to other GI conditions such as SIBO, celiac disease, and functional bowel disorders, gauging whether a patient has risk factors for EPI will help the clinician understand how likely a diagnosis of EPI may be and if and what testing would be appropriate.

In my practice, I consider diagnostic testing in patients who may be at risk for EPI and have mild symptoms such malodorous gas, bloating and mild steatorrhea. For patient with clear evidence of steatorrhea (weight loss and vitamin deficiencies) and have strong risk factors for EPI (i.e. heavy alcohol and tobacco and/or a history of recurrent or severe acute pancreatitis), I might consider imaging and/or empiric therapies as to expedite care.

How difficult is it to diagnose EPI and what steps do you take to ensure that you prescribe patients with the proper therapy?

Dr. Kothari: The diagnosis of pancreatic insufficiency, in my mind, needs to start with assessing the pre-test probability of the patient having EPI, since testing could lead to a false positive.

The test of choice in most scenarios for diagnosing pancreatic insufficiency is a stool test known as the fecal elastase. It is a measurement of pancreatic elastase in the stool. The test itself is a concentration. For any condition that results in a dilute stool sample, that'll result in a falsely low value that can give a patient a false positive test. Now, this can be corrected by the lab concentrating the stool sample before running the test, but that testing center needs to know how to do that.

The other assumption that we make with this stool test is that we assume that the elastase is a stable molecule that can traverse all the gut and be collected adequately. And for any reason, if that enzyme is degraded for any reason, it's also going to provide a low test, a low result, resulting in a false positive.

If they have risk factors for chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic disease and they're presenting with symptoms of EPI, then the usual test that I'll choose is dedicated pancreatic imaging such as an MRI or dedicated CT pancreatic imaging, or endoscopic ultrasound. If we clinch a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and they have symptoms of pancreatic insufficiency, I think that’s enough to presume a diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and start treatment.

On the other hand, in patients who do not have risk factors for pancreatic disease but there remains some clinical suspicion for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, then it may be reasonable to check a fecal elastase to rule out pancreatic insufficiency. If the test results are low, then follow-up dedicated pancreas imaging would be the next step in delineating intrinsic pancreatic conditions form extra-pancreatic causes. If pancreas imaging effectively rules out pancreatic disease then I consider checking for celiac disease, ruling out small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and considering assessment of luminal motility (either with a capsule or small bowel follow through). Although functional neuroendocrine tumors have been previously considered a cause of EPI, these tumors tend to present with secretory diarrhea which typically present differently (and often more dramatically) than other causes of EPI. Thus, I do not routinely check vasoactive hormone levels.

I think the American Gastroenterological Association has great patient education documents for our patients. Thus, I would encourage our colleagues to use the AGA for their resources for our patients on EPI.

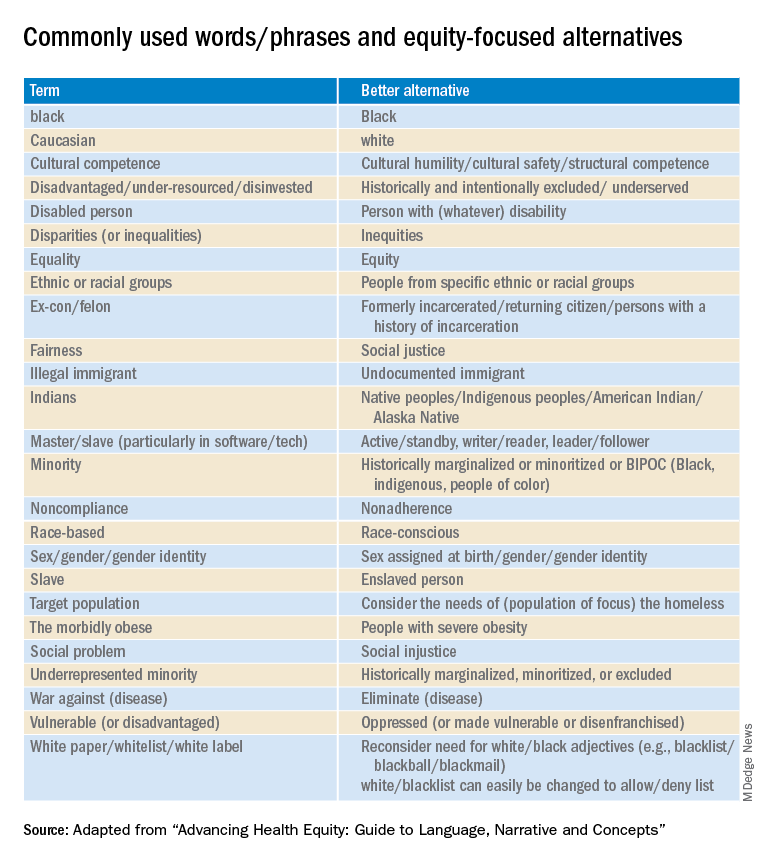

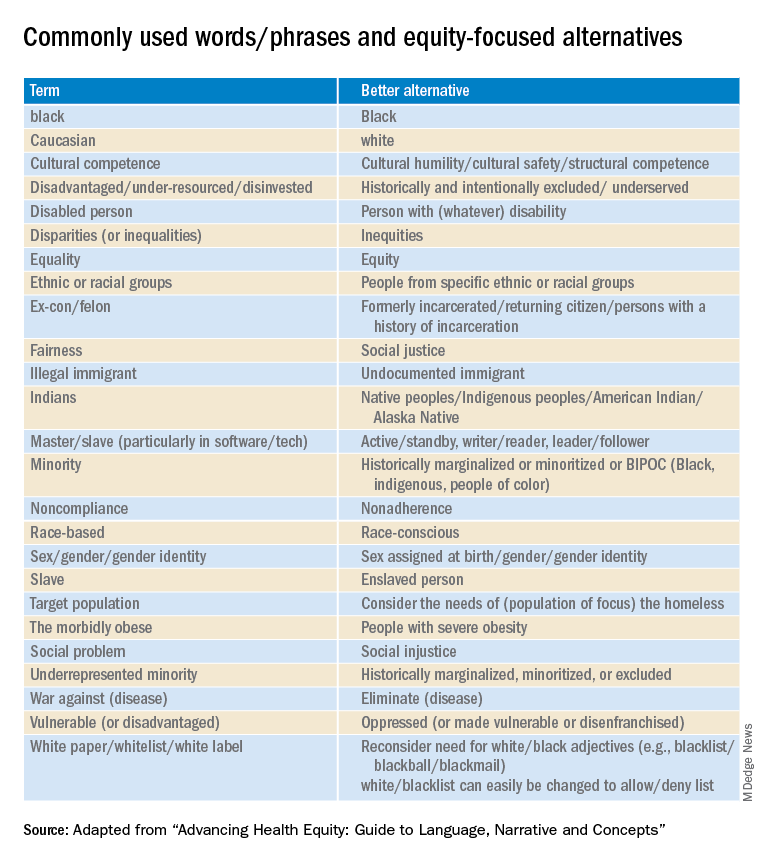

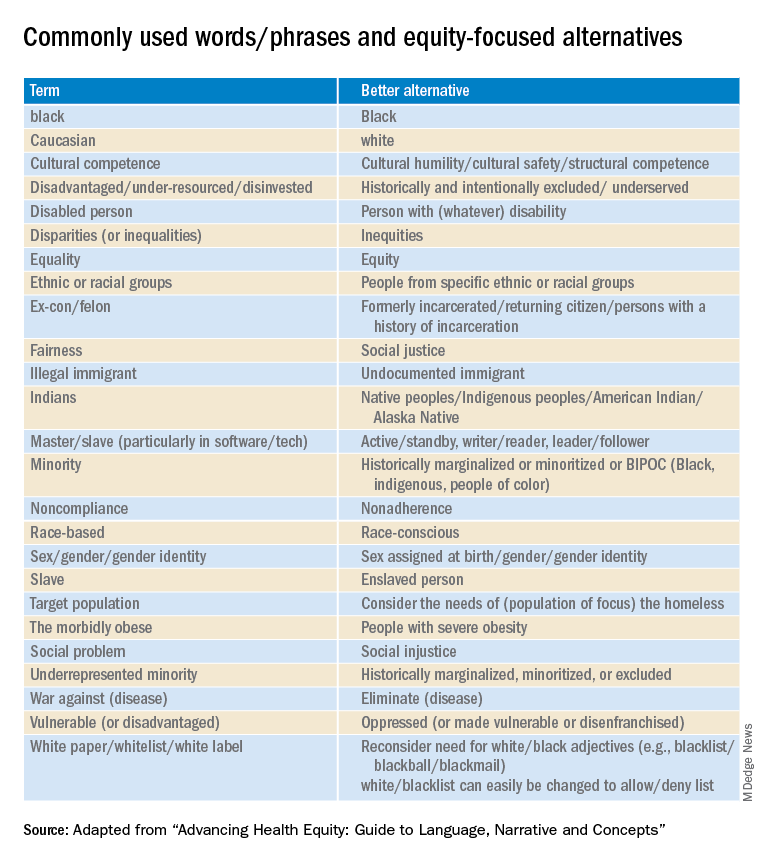

How and why the language of medicine must change

The United States has never achieved a single high standard of medical care equity for all of its people, and the trend line does not appear favorable. The closest we have reached is basic Medicare (Parts A and B), military medicine, the Veterans Health Administration, and large nonprofit groups like Kaiser Permanente. It seems that the nature of we individualistic Americans is to always try to seek an advantage.

But even achieving equity in medical care would not ensure equity in health. The social determinants of health (income level, education, politics, government, geography, neighborhood, country of origin, language spoken, literacy, gender, and yes – race and ethnicity) have far more influence on health equity than does medical care.

Narratives can both reflect and influence culture. Considering the harmful effects of the current political divisiveness in the United States, the timing is ideal for our three leading medical and health education organizations – the American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – to publish a definitive position paper called “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts.”

What’s in a word?

According to William Shakespeare, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” (Romeo and Juliet). Maybe. But if the word used were “thorn” or “thistle,” it just would not be the same.

Words comprise language and wield enormous power with human beings. Wars are fought over geographic boundaries often defined by the language spoken by the people: think 2022, Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Think Winston Churchill’s massive 1,500-page “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Think about the political power of French in Quebec, Canada.

Thus, it should be no surprise that words, acronyms, and abbreviations become rallying cries for political activists of all stripes: PC, January 6, Woke, 1619, BLM, Critical Race Theory, 1776, Remember Pearl Harbor, Remember the Alamo, the Civil War or the War Between the States, the War for Southern Independence, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of the Rebellion, or simply “The Lost Cause.” How about Realpolitik?

Is “medical language” the language of the people or of the profession? Physicians must understand each other, and physicians also must communicate clearly with patients using words that convey neutral meanings and don’t interfere with objective understanding. Medical editors prefer the brevity of one or a few words to clearly convey meaning.

I consider this document from the AMA and AAMC to be both profound and profoundly important for the healing professions. The contributors frequently use words like “humility” as they describe their efforts and products, knowing full well that they (and their organizations) stand to be figuratively torn limb from limb by a host of critics – or worse, ignored and marginalized.

Part 1 of the Health Equity Guide is titled “Language for promoting health equity.”(the reader is referred to the Health Equity Guide for the reasoning and explanations for all).

Part 2 of the Health Equity Guide is called “Why narratives matter.” It includes features of dominant narratives; a substantial section on the narrative of race and the narrative of individualism; the purpose of a health equity–based narrative; how to change the narrative; and how to see and think critically through dialogue.

Part 3 of the Health Equity Guide is a glossary of 138 key terms such as “class,” “discrimination,” “gender dysphoria,” “non-White,” “racial capitalism,” and “structural competency.”

The CDC also has a toolkit for inclusive communication, the “Health Equity Guiding Principles for Inclusive Communication.”

The substantive message of the Health Equity Guide could affect what you say, write, and do (even how you think) every day as well as how those with whom you interact view you. It can affect the entire communication milieu in which you live, whether or not you like it. Read it seriously, as though your professional life depended on it. It may.

Dr. Lundberg is consulting professor of health research policy and pathology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States has never achieved a single high standard of medical care equity for all of its people, and the trend line does not appear favorable. The closest we have reached is basic Medicare (Parts A and B), military medicine, the Veterans Health Administration, and large nonprofit groups like Kaiser Permanente. It seems that the nature of we individualistic Americans is to always try to seek an advantage.

But even achieving equity in medical care would not ensure equity in health. The social determinants of health (income level, education, politics, government, geography, neighborhood, country of origin, language spoken, literacy, gender, and yes – race and ethnicity) have far more influence on health equity than does medical care.

Narratives can both reflect and influence culture. Considering the harmful effects of the current political divisiveness in the United States, the timing is ideal for our three leading medical and health education organizations – the American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – to publish a definitive position paper called “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts.”

What’s in a word?

According to William Shakespeare, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” (Romeo and Juliet). Maybe. But if the word used were “thorn” or “thistle,” it just would not be the same.

Words comprise language and wield enormous power with human beings. Wars are fought over geographic boundaries often defined by the language spoken by the people: think 2022, Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Think Winston Churchill’s massive 1,500-page “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Think about the political power of French in Quebec, Canada.

Thus, it should be no surprise that words, acronyms, and abbreviations become rallying cries for political activists of all stripes: PC, January 6, Woke, 1619, BLM, Critical Race Theory, 1776, Remember Pearl Harbor, Remember the Alamo, the Civil War or the War Between the States, the War for Southern Independence, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of the Rebellion, or simply “The Lost Cause.” How about Realpolitik?

Is “medical language” the language of the people or of the profession? Physicians must understand each other, and physicians also must communicate clearly with patients using words that convey neutral meanings and don’t interfere with objective understanding. Medical editors prefer the brevity of one or a few words to clearly convey meaning.

I consider this document from the AMA and AAMC to be both profound and profoundly important for the healing professions. The contributors frequently use words like “humility” as they describe their efforts and products, knowing full well that they (and their organizations) stand to be figuratively torn limb from limb by a host of critics – or worse, ignored and marginalized.

Part 1 of the Health Equity Guide is titled “Language for promoting health equity.”(the reader is referred to the Health Equity Guide for the reasoning and explanations for all).

Part 2 of the Health Equity Guide is called “Why narratives matter.” It includes features of dominant narratives; a substantial section on the narrative of race and the narrative of individualism; the purpose of a health equity–based narrative; how to change the narrative; and how to see and think critically through dialogue.

Part 3 of the Health Equity Guide is a glossary of 138 key terms such as “class,” “discrimination,” “gender dysphoria,” “non-White,” “racial capitalism,” and “structural competency.”

The CDC also has a toolkit for inclusive communication, the “Health Equity Guiding Principles for Inclusive Communication.”

The substantive message of the Health Equity Guide could affect what you say, write, and do (even how you think) every day as well as how those with whom you interact view you. It can affect the entire communication milieu in which you live, whether or not you like it. Read it seriously, as though your professional life depended on it. It may.

Dr. Lundberg is consulting professor of health research policy and pathology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States has never achieved a single high standard of medical care equity for all of its people, and the trend line does not appear favorable. The closest we have reached is basic Medicare (Parts A and B), military medicine, the Veterans Health Administration, and large nonprofit groups like Kaiser Permanente. It seems that the nature of we individualistic Americans is to always try to seek an advantage.

But even achieving equity in medical care would not ensure equity in health. The social determinants of health (income level, education, politics, government, geography, neighborhood, country of origin, language spoken, literacy, gender, and yes – race and ethnicity) have far more influence on health equity than does medical care.

Narratives can both reflect and influence culture. Considering the harmful effects of the current political divisiveness in the United States, the timing is ideal for our three leading medical and health education organizations – the American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – to publish a definitive position paper called “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts.”

What’s in a word?

According to William Shakespeare, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” (Romeo and Juliet). Maybe. But if the word used were “thorn” or “thistle,” it just would not be the same.

Words comprise language and wield enormous power with human beings. Wars are fought over geographic boundaries often defined by the language spoken by the people: think 2022, Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Think Winston Churchill’s massive 1,500-page “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Think about the political power of French in Quebec, Canada.

Thus, it should be no surprise that words, acronyms, and abbreviations become rallying cries for political activists of all stripes: PC, January 6, Woke, 1619, BLM, Critical Race Theory, 1776, Remember Pearl Harbor, Remember the Alamo, the Civil War or the War Between the States, the War for Southern Independence, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of the Rebellion, or simply “The Lost Cause.” How about Realpolitik?

Is “medical language” the language of the people or of the profession? Physicians must understand each other, and physicians also must communicate clearly with patients using words that convey neutral meanings and don’t interfere with objective understanding. Medical editors prefer the brevity of one or a few words to clearly convey meaning.

I consider this document from the AMA and AAMC to be both profound and profoundly important for the healing professions. The contributors frequently use words like “humility” as they describe their efforts and products, knowing full well that they (and their organizations) stand to be figuratively torn limb from limb by a host of critics – or worse, ignored and marginalized.

Part 1 of the Health Equity Guide is titled “Language for promoting health equity.”(the reader is referred to the Health Equity Guide for the reasoning and explanations for all).

Part 2 of the Health Equity Guide is called “Why narratives matter.” It includes features of dominant narratives; a substantial section on the narrative of race and the narrative of individualism; the purpose of a health equity–based narrative; how to change the narrative; and how to see and think critically through dialogue.

Part 3 of the Health Equity Guide is a glossary of 138 key terms such as “class,” “discrimination,” “gender dysphoria,” “non-White,” “racial capitalism,” and “structural competency.”

The CDC also has a toolkit for inclusive communication, the “Health Equity Guiding Principles for Inclusive Communication.”

The substantive message of the Health Equity Guide could affect what you say, write, and do (even how you think) every day as well as how those with whom you interact view you. It can affect the entire communication milieu in which you live, whether or not you like it. Read it seriously, as though your professional life depended on it. It may.

Dr. Lundberg is consulting professor of health research policy and pathology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Question 2

Correct answer: B. Absence of ganglion cells on rectal biopsy.

Rationale

Hirschsprung's disease occurs in approximately 1 out of 5,000 live births and is caused by absence of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of the intestine. The condition arises from failure of the neural crest cells to fully migrate caudally along the intestine during early gestation, resulting in a distal portion of the intestine being aganglionic. Rectal and distal sigmoid involvement is seen in around 85% of cases, with the other 15 percent involving more proximal intestine. It can rarely involve the entire colon and small intestine. Ganglion cells inhibit local smooth muscles, resulting in the characteristic inability for aganglionic bowel to relax. This lack of inhibition gives rise to the absence of rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIRs) during anorectal manometry. The lack of inhibition also produces a transition zone on contrast enema, with the distal aganglionic bowel being narrow and the more proximal bowel containing ganglia being dilated. Lack of meconium passage in the first 48 hours of life raises concern for Hirschsprung's disease. Other causes for possible failure to pass meconium include cystic fibrosis, anorectal malformation, small left colon syndrome, meconium plug syndrome and megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome.

References

Kenny, S et al. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010 Aug;19(3):194-200.

Wyllie R et al. Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 4th edition. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, 2011.

Correct answer: B. Absence of ganglion cells on rectal biopsy.

Rationale

Hirschsprung's disease occurs in approximately 1 out of 5,000 live births and is caused by absence of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of the intestine. The condition arises from failure of the neural crest cells to fully migrate caudally along the intestine during early gestation, resulting in a distal portion of the intestine being aganglionic. Rectal and distal sigmoid involvement is seen in around 85% of cases, with the other 15 percent involving more proximal intestine. It can rarely involve the entire colon and small intestine. Ganglion cells inhibit local smooth muscles, resulting in the characteristic inability for aganglionic bowel to relax. This lack of inhibition gives rise to the absence of rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIRs) during anorectal manometry. The lack of inhibition also produces a transition zone on contrast enema, with the distal aganglionic bowel being narrow and the more proximal bowel containing ganglia being dilated. Lack of meconium passage in the first 48 hours of life raises concern for Hirschsprung's disease. Other causes for possible failure to pass meconium include cystic fibrosis, anorectal malformation, small left colon syndrome, meconium plug syndrome and megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome.

References

Kenny, S et al. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010 Aug;19(3):194-200.

Wyllie R et al. Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 4th edition. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, 2011.

Correct answer: B. Absence of ganglion cells on rectal biopsy.

Rationale

Hirschsprung's disease occurs in approximately 1 out of 5,000 live births and is caused by absence of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of the intestine. The condition arises from failure of the neural crest cells to fully migrate caudally along the intestine during early gestation, resulting in a distal portion of the intestine being aganglionic. Rectal and distal sigmoid involvement is seen in around 85% of cases, with the other 15 percent involving more proximal intestine. It can rarely involve the entire colon and small intestine. Ganglion cells inhibit local smooth muscles, resulting in the characteristic inability for aganglionic bowel to relax. This lack of inhibition gives rise to the absence of rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIRs) during anorectal manometry. The lack of inhibition also produces a transition zone on contrast enema, with the distal aganglionic bowel being narrow and the more proximal bowel containing ganglia being dilated. Lack of meconium passage in the first 48 hours of life raises concern for Hirschsprung's disease. Other causes for possible failure to pass meconium include cystic fibrosis, anorectal malformation, small left colon syndrome, meconium plug syndrome and megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome.

References

Kenny, S et al. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010 Aug;19(3):194-200.

Wyllie R et al. Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 4th edition. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, 2011.

A 2-month-old male presents with abdominal distention and poor appetite. His family notes that the patient has chronic difficulties with constipation, reporting that they have to use a glycerin suppository to help him have a bowel movement every 2-3 days. The family reports that he even needed a suppository in the newborn nursey at day of life 3 due to lack of passage of meconium.

Question 1

Correct answer: A. Amyloidosis involving the small intestine

Rationale

This patient has a protein-losing enteropathy as indicated by his diarrhea, peripheral edema, and positive stool alpha-1 antitrypsin test. Multiple diseases, particularly in their later stages, can be associated with a protein-losing enteropathy including primary intestinal lymphangectasia, Crohn's disease of the small intestine, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and amyloidosis of the small intestine (A). Celiac disease (B) is not associated with protein-losing enteropathy. While Crohn's disease can be associated with protein-losing enteropathy, ulcerative colitis (C) is not usually associated with it. Small bowel dysmotility (D) does not impact absorption or secretion unless associated with SIBO, making this a wrong answer.

Correct answer: A. Amyloidosis involving the small intestine

Rationale