User login

Are Breast Cancer Patients Satisfied With Their Care?

Japan has a universal health care system with low copays and short wait times for appointments, including those with specialists. Yet patient satisfaction scores are low compared with those of other countries. Researchers from Juntendo Urayasu Hospital, a university hospital in a Tokyo suburb, conducted a study of 214 patients with breast cancer to find out which aspects of radiation oncology care might affect patient satisfaction. The survey included questions about overall treatment, time from diagnosis to treatment start, wait times in the hospital, and length of consultations.

In general, levels of satisfaction were high. However, wait time was significantly negatively associated with both overall satisfaction and satisfaction with the radiation oncologist. Wait time was just under an hour for an average 11-minute consultation. Although this was longer than the “notorious” Japanese situation of a “3 hours wait and 3 minutes consultation,” the researchers say, “We expect that an international audience will appreciate that even 11 minutes is an exceptionally short duration for a consultation visit with a specialist in radiation oncology.”

They note, though, a reasonable caveat. Anyone can walk into their hospital and, for an additional fee, see a specialist on the day they want, which can lead to extended wait times from sheer congestion. Their hospital’s chief breast cancer surgeon sees 60 to 70 patients a day; the radiation oncologist treats 500 to 600 patients a year without resident or trainee support. This situation is typical of Japanese university hospitals, the researchers add.

Related: Breast Cancer Treatment Among Rural and Urban Women at the Veterans Health Administration

Importantly, for Japanese patients, the researchers also included questions to measure patients’ opinions about sharing how they felt with their physicians. The level of sharing correlated with satisfaction, but the researchers point out that in Japan sharing feelings remains “challenging.” Their findings suggest, they say, that if this were improved, patients’ satisfaction might increase.

Japan has a universal health care system with low copays and short wait times for appointments, including those with specialists. Yet patient satisfaction scores are low compared with those of other countries. Researchers from Juntendo Urayasu Hospital, a university hospital in a Tokyo suburb, conducted a study of 214 patients with breast cancer to find out which aspects of radiation oncology care might affect patient satisfaction. The survey included questions about overall treatment, time from diagnosis to treatment start, wait times in the hospital, and length of consultations.

In general, levels of satisfaction were high. However, wait time was significantly negatively associated with both overall satisfaction and satisfaction with the radiation oncologist. Wait time was just under an hour for an average 11-minute consultation. Although this was longer than the “notorious” Japanese situation of a “3 hours wait and 3 minutes consultation,” the researchers say, “We expect that an international audience will appreciate that even 11 minutes is an exceptionally short duration for a consultation visit with a specialist in radiation oncology.”

They note, though, a reasonable caveat. Anyone can walk into their hospital and, for an additional fee, see a specialist on the day they want, which can lead to extended wait times from sheer congestion. Their hospital’s chief breast cancer surgeon sees 60 to 70 patients a day; the radiation oncologist treats 500 to 600 patients a year without resident or trainee support. This situation is typical of Japanese university hospitals, the researchers add.

Related: Breast Cancer Treatment Among Rural and Urban Women at the Veterans Health Administration

Importantly, for Japanese patients, the researchers also included questions to measure patients’ opinions about sharing how they felt with their physicians. The level of sharing correlated with satisfaction, but the researchers point out that in Japan sharing feelings remains “challenging.” Their findings suggest, they say, that if this were improved, patients’ satisfaction might increase.

Japan has a universal health care system with low copays and short wait times for appointments, including those with specialists. Yet patient satisfaction scores are low compared with those of other countries. Researchers from Juntendo Urayasu Hospital, a university hospital in a Tokyo suburb, conducted a study of 214 patients with breast cancer to find out which aspects of radiation oncology care might affect patient satisfaction. The survey included questions about overall treatment, time from diagnosis to treatment start, wait times in the hospital, and length of consultations.

In general, levels of satisfaction were high. However, wait time was significantly negatively associated with both overall satisfaction and satisfaction with the radiation oncologist. Wait time was just under an hour for an average 11-minute consultation. Although this was longer than the “notorious” Japanese situation of a “3 hours wait and 3 minutes consultation,” the researchers say, “We expect that an international audience will appreciate that even 11 minutes is an exceptionally short duration for a consultation visit with a specialist in radiation oncology.”

They note, though, a reasonable caveat. Anyone can walk into their hospital and, for an additional fee, see a specialist on the day they want, which can lead to extended wait times from sheer congestion. Their hospital’s chief breast cancer surgeon sees 60 to 70 patients a day; the radiation oncologist treats 500 to 600 patients a year without resident or trainee support. This situation is typical of Japanese university hospitals, the researchers add.

Related: Breast Cancer Treatment Among Rural and Urban Women at the Veterans Health Administration

Importantly, for Japanese patients, the researchers also included questions to measure patients’ opinions about sharing how they felt with their physicians. The level of sharing correlated with satisfaction, but the researchers point out that in Japan sharing feelings remains “challenging.” Their findings suggest, they say, that if this were improved, patients’ satisfaction might increase.

The Long Legacy of Agent Orange

For some veterans, exposure to Agent Orange and its many health ramifications is an ongoing concern—even though they might have been exposed more than 50 years ago. Clinicians from Sinai Hospital of Baltimore in Maryland report on a patient who reminded them that a current illness could be related to that long-ago exposure.

Related: Bladder Cancer and Hyperthyroidism Linked to Agent Orange

The 69-year-old man came to their clinic with a painful, enlarging mass of the right lateral thigh, which ultrasound revealed as a myxofibrosarcoma. He underwent radical excision of the sarcoma with adjuvant radiotherapy. Histologic examination revealed an 8.3 cm, grade 3 pleomorphic liposarcoma. The patient asked, “Was it related to Agent Orange?” It may have been, the clinicians decided.

Agent Orange tends to accumulate in the liver and adipose tissue; it also affects lipid metabolism and may lead to hyperlipidemia. Although in the early days after the Vietnam War, many pathologies were labeled as “stress induced,” a number of illnesses have since been linked to Agent Orange, including B-cell leukemia, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, prostate cancer, and, perhaps, multiple myeloma. But the authors say the toxin’s role in sarcomagenesis has been controversial in part because of conflicting case-control studies and because large-scale clinical trials are not feasible.

Related: Link Found Between Agent Orange Exposure and Multiple Myeloma

There has been no well-established precipitating factor for liposarcoma, the authors note. But they suggest that clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion for persistent and evolving soft tissue masses in patients with a previous military background, which should prompt the search for a possible toxin exposure.

Their patient experienced the enlarging soft tissue mass over the course of a year. A simple question: “Have you ever been in the military or had any previous wartime toxin exposure?” early on would have impelled the physicians to do a swifter workup, the authors say, particularly in a case with high risk of metastasis and poor prognosis. The patient will continue to be monitored “for years,” the authors say.

“While these days we have access to a vast amount of diagnostic tests and imaging,” the authors conclude, “one cannot underestimate the importance of understanding a patient’s past history.”

Source:

Khan K, Wozniak SE, Coleman J, Didolkar MS. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2016217438.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217438.

For some veterans, exposure to Agent Orange and its many health ramifications is an ongoing concern—even though they might have been exposed more than 50 years ago. Clinicians from Sinai Hospital of Baltimore in Maryland report on a patient who reminded them that a current illness could be related to that long-ago exposure.

Related: Bladder Cancer and Hyperthyroidism Linked to Agent Orange

The 69-year-old man came to their clinic with a painful, enlarging mass of the right lateral thigh, which ultrasound revealed as a myxofibrosarcoma. He underwent radical excision of the sarcoma with adjuvant radiotherapy. Histologic examination revealed an 8.3 cm, grade 3 pleomorphic liposarcoma. The patient asked, “Was it related to Agent Orange?” It may have been, the clinicians decided.

Agent Orange tends to accumulate in the liver and adipose tissue; it also affects lipid metabolism and may lead to hyperlipidemia. Although in the early days after the Vietnam War, many pathologies were labeled as “stress induced,” a number of illnesses have since been linked to Agent Orange, including B-cell leukemia, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, prostate cancer, and, perhaps, multiple myeloma. But the authors say the toxin’s role in sarcomagenesis has been controversial in part because of conflicting case-control studies and because large-scale clinical trials are not feasible.

Related: Link Found Between Agent Orange Exposure and Multiple Myeloma

There has been no well-established precipitating factor for liposarcoma, the authors note. But they suggest that clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion for persistent and evolving soft tissue masses in patients with a previous military background, which should prompt the search for a possible toxin exposure.

Their patient experienced the enlarging soft tissue mass over the course of a year. A simple question: “Have you ever been in the military or had any previous wartime toxin exposure?” early on would have impelled the physicians to do a swifter workup, the authors say, particularly in a case with high risk of metastasis and poor prognosis. The patient will continue to be monitored “for years,” the authors say.

“While these days we have access to a vast amount of diagnostic tests and imaging,” the authors conclude, “one cannot underestimate the importance of understanding a patient’s past history.”

Source:

Khan K, Wozniak SE, Coleman J, Didolkar MS. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2016217438.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217438.

For some veterans, exposure to Agent Orange and its many health ramifications is an ongoing concern—even though they might have been exposed more than 50 years ago. Clinicians from Sinai Hospital of Baltimore in Maryland report on a patient who reminded them that a current illness could be related to that long-ago exposure.

Related: Bladder Cancer and Hyperthyroidism Linked to Agent Orange

The 69-year-old man came to their clinic with a painful, enlarging mass of the right lateral thigh, which ultrasound revealed as a myxofibrosarcoma. He underwent radical excision of the sarcoma with adjuvant radiotherapy. Histologic examination revealed an 8.3 cm, grade 3 pleomorphic liposarcoma. The patient asked, “Was it related to Agent Orange?” It may have been, the clinicians decided.

Agent Orange tends to accumulate in the liver and adipose tissue; it also affects lipid metabolism and may lead to hyperlipidemia. Although in the early days after the Vietnam War, many pathologies were labeled as “stress induced,” a number of illnesses have since been linked to Agent Orange, including B-cell leukemia, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, prostate cancer, and, perhaps, multiple myeloma. But the authors say the toxin’s role in sarcomagenesis has been controversial in part because of conflicting case-control studies and because large-scale clinical trials are not feasible.

Related: Link Found Between Agent Orange Exposure and Multiple Myeloma

There has been no well-established precipitating factor for liposarcoma, the authors note. But they suggest that clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion for persistent and evolving soft tissue masses in patients with a previous military background, which should prompt the search for a possible toxin exposure.

Their patient experienced the enlarging soft tissue mass over the course of a year. A simple question: “Have you ever been in the military or had any previous wartime toxin exposure?” early on would have impelled the physicians to do a swifter workup, the authors say, particularly in a case with high risk of metastasis and poor prognosis. The patient will continue to be monitored “for years,” the authors say.

“While these days we have access to a vast amount of diagnostic tests and imaging,” the authors conclude, “one cannot underestimate the importance of understanding a patient’s past history.”

Source:

Khan K, Wozniak SE, Coleman J, Didolkar MS. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2016217438.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217438.

Patient Knowledge and Attitudes About Fecal Microbiota Therapy for Clostridium difficile Infection

Clostridium difficile (C difficile) infection (CDI) is a leading cause of infectious diarrhea among hospitalized patients and, increasingly, in ambulatory patients.1,2 The high prevalence of CDI and the high recurrence rates (15%-30%) led the CDC to categorize C difficile as an "urgent" threat (the highest category) in its 2013 Antimicrobial Resistance Threat Report.3-5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommended treatment for CDI is vancomycin or metronidazole; more recent studies also support fidaxomicin use.4,6,7

Patients experiencing recurrent CDI are at risk for further recurrences, such that after the third CDI episode, the risk of subsequent recurrences exceeds 50%.8 This recurrence rate has stimulated research into other treatments, including fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). A recent systematic review of FMT reports that 85% of patients have resolution of symptoms without recurrence after FMT, although this is based on data from case series and 2 small randomized clinical trials.9

A commonly cited barrier to FMT is patient acceptance. In response to this concern, a previous survey demonstrated that 81% of respondents would opt for FMT to treat a hypothetical case of recurrent CDI.10 However, the surveyed population did not have CDI, and the 48% response rate is concerning, since those with a favorable opinion of FMT might be more willing to complete a survey than would other patients. Accordingly, the authors systematically surveyed hospitalized veterans with active CDI to assess their knowledge, attitudes, and opinions about FMT as a treatment for CDI.

Methods

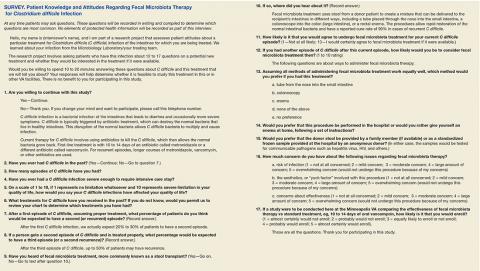

In-person patient interviews were conducted by one of the study authors at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS), consisting of 13 to 18 questions. Questions addressed any prior CDI episodes and knowledge of the following: CDI, recurrence risk, and FMT; preferred route and location of FMT administration; concerns regarding FMT; likelihood of agreeing to undergo FMT (if available); and likelihood of enrollment in a hypothetical study comparing FMT to standard antibiotic treatment. The survey was developed internally and was not validated. Questions used the Likert-scale (Survey).

Patients with CDI were identified by monitoring for positive C difficile polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stool tests and then screened for inclusion by medical record review. Inclusion criteria were (1) MVAHCS hospitalization; and (2) written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were the inability to communicate or participate in an interview. Patient responses regarding their likelihood of agreeing to FMT for CDI treatment under different circumstances were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. These circumstances included FMT for their current episode of CDI, FMT for a subsequent episode, and FMT if recommended by their physician. Possible concerns regarding FMT also were solicited, including infection risk, effectiveness, and procedural aesthetics. The MVAHCS institutional review board approved the study.

Results

Stool PCR tests for CDI were monitored for 158 days from 2013 to 2014 (based on availability of study staff), yielding 106 positive results. Of those, 31 (29%) were from outpatients and not addressed further. Of the 75 positive CDI tests from 66 hospitalized patients (9 patients had duplicate tests), 18 of 66 (27%) were not able to provide consent and were excluded, leaving 48 eligible patients. Six (13%) were missed for logistic reasons (patient at a test or procedure, discharged before approached, etc), leaving 42 patients who were approached for participation. Among these, 34 (81%) consented to participate in the survey. Two subjects (6%) found the topic so unappealing that they terminated the interview.

The majority of enrolled subjects were men (32/34, 94%), with a mean age of 65.3 years (range, 31-89). Eleven subjects (32%) reported a prior CDI episode, with 10 reporting 1 such episode, and the other 2 episodes. Those with prior CDI reported the effect of CDI on their overall quality of life as 5.1 (1 = no limitation, 10 = severe limitation). Respondents were fairly accurate regarding the risk of recurrence after an initial episode of CDI, with the average expectedrecurrence rate estimated at 33%. In contrast, their estimation of the risk of recurrence after a second CDI episode was lower (28%), although the risk of recurrent episodes increases with each CDI recurrence.

Regarding FMT, 5 subjects indicated awareness of the procedure: 2 learning of it from a news source, 1 from family, 1 from a health care provider, and 1 was unsure of the source. After subjects received a description of FMT, their opinions regarding the procedure were elicited. When asked which route of delivery they would prefer if they were to undergo FMT, the 33 subjects who provided a response indicated a strong preference for either enema (15, 45%) or colonoscopy (10, 30%), compared with just 4 (12%) indicating no preference, 2 (6%) choosing nasogastric tube administration, and 2 (6%) indicating that they would not undergo FMT by any route (P < .001).

Regarding the location of FMT administration (hospital setting vs self-administered at home), 31 of 33 respondents (94%) indicated they would prefer FMT to occur in the hospital vs 2 (6%) preferring self-administration at home (P < .001). The preferred source of donor stool was more evenly distributed, with 14 of 32 respondents (44%) indicating a preference for an anonymous donor, 11 preferring a family member (34%), and 7 (21%) with no preference (P = .21).

Subjects were asked about concerns regarding FMT, and asked to rate each on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all concerning; 5 = overwhelming concern). Concerns regarding risk of infection and effectiveness received an average score of 2.74 and 2.72, respectively, whereas concern regarding the aesthetics, or "yuck factor" was slightly lower (2.1: P = NS for all comparisons). Subjects also were asked to rate the likelihood of undergoing FMT, if it were available, for their current episode of CDI, a subsequent episode of CDI, or if their physician recommended undergoing FMT (10 point scale: 1 = not at all likely; 10 = certainly agree to FMT). The mean scores (SD) for agreeing to FMT for the current or a subsequent episode were 4.8 (SD 2.7) and 5.6 (SD 3.0); P = .12, but increased to 7.1 (SD 3.23) if FMT were recommended by their physician (P < .001 for FMT if physician recommended vs FMT for current episode; P = .001 for FMT if physician recommended vs FMT for a subsequent episode). Finally, subjects were asked about the likelihood of enrolling in a study comparing FMT to standard antimicrobial treatment, with answers ranging from 1 (almost certainly would not enroll) to 5 (almost certainly would enroll). Among the 32 respondents to this question, 17 (53%) answered either "probably would enroll" or "almost certainly would enroll," with a mean score of 3.2.

Discussion

Overall, VA patients with a current episode of CDI were not aware of FMT, with just 15% knowing about the procedure. However, after learning about FMT, patients expressed clear opinions regarding the route and setting of FMT administration, with enema or colonoscopy being the preferred routes, and a hospital the preferred setting. In contrast, subjects expressed ambivalence with regard to the source of donor stool, with no clear preference for stool from an anonymous donor vs from a family member.

When asked about concerns regarding FMT, none of the presented options (risk of infection, uncertain effectiveness, or procedural aesthetics) emerged as significantly more important than did others, although the oft-cited concern regarding FMT aesthetics engendered the lowest overall level of concern. In terms of FMT acceptance, 4 subjects (12%) were opposed to the procedure, indicating that they were not at all likely to agree to FMT for all scenarios (defined as a score of 1 or 2 on the 10-point Likert scale) or by terminating the survey because of the questions. However, 15 (44%) indicated that they would certainly agree to FMT (defined as a score of 9 or 10 on the 10-point Likert scale) if their physician recommended it. Physician recommendation for FMT resulted in the highest overall likelihood of agreeing to FMT, a finding in agreement with a previous survey of FMT for CDI.10 Most subjects indicated likely enrollment in a potential study comparing FMT with standard antimicrobial therapy.

Strengths/Limitations

Study strengths included surveying patients with current CDI, such that patients had personal experience with the disease in question. Use of in-person interviews also resulted in a robust response rate of 81% and allowed subjects to clarify any unclear questions with study personnel. Weaknesses included a relatively small sample size, underrepresentation of women, and lack of detail regarding respondent characteristics. Additionally, capsule delivery of FMT was not assessed since this method of delivery had not been published at the time of survey administration.

Conclusion

This survey of VA patients with CDI suggests that aesthetic concerns are not a critical deterrent for this population, and interest in FMT for the treatment of recurrent CDI exists. Physician recommendation to undergo FMT seems to be the most influential factor affecting the likelihood of agreeing to undergo FMT. These results support the feasibility of conducting clinical trials of FMT in the VA system.

1. Miller BA, Chen LF, Sexton DJ, Anderson DJ. Comparison of the burdens of hospital-onset, healthcare facility-associated Clostridium difficile Infection and of healthcare-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(4):387-390.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Clostridium difficile-associated disease in populations previously at low risk--four states, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(47):1201-1205.

3. Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al; Polymer Alternative for CDI Treatment (PACT) investigators. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(3):345-354.

4. Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al; OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):422-431.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013. Updated July 17, 2014. Accessed November 16.2016.

6. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

7. Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, et al; OPT-80-004 Clinical Study Group. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(4):281-289.

8. Johnson S. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a review of risk factors, treatments, and outcomes. J Infect. 2009;58(6):403-410.

9. Drekonja DM, Reich J, Gezahegn S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection--a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9):630-638.

10. Zipursky JS, Sidorsky TI, Freedman CA, Sidorsky MN, Kirkland KB. Patient attitudes toward the use of fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(12):1652-1658.

Clostridium difficile (C difficile) infection (CDI) is a leading cause of infectious diarrhea among hospitalized patients and, increasingly, in ambulatory patients.1,2 The high prevalence of CDI and the high recurrence rates (15%-30%) led the CDC to categorize C difficile as an "urgent" threat (the highest category) in its 2013 Antimicrobial Resistance Threat Report.3-5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommended treatment for CDI is vancomycin or metronidazole; more recent studies also support fidaxomicin use.4,6,7

Patients experiencing recurrent CDI are at risk for further recurrences, such that after the third CDI episode, the risk of subsequent recurrences exceeds 50%.8 This recurrence rate has stimulated research into other treatments, including fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). A recent systematic review of FMT reports that 85% of patients have resolution of symptoms without recurrence after FMT, although this is based on data from case series and 2 small randomized clinical trials.9

A commonly cited barrier to FMT is patient acceptance. In response to this concern, a previous survey demonstrated that 81% of respondents would opt for FMT to treat a hypothetical case of recurrent CDI.10 However, the surveyed population did not have CDI, and the 48% response rate is concerning, since those with a favorable opinion of FMT might be more willing to complete a survey than would other patients. Accordingly, the authors systematically surveyed hospitalized veterans with active CDI to assess their knowledge, attitudes, and opinions about FMT as a treatment for CDI.

Methods

In-person patient interviews were conducted by one of the study authors at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS), consisting of 13 to 18 questions. Questions addressed any prior CDI episodes and knowledge of the following: CDI, recurrence risk, and FMT; preferred route and location of FMT administration; concerns regarding FMT; likelihood of agreeing to undergo FMT (if available); and likelihood of enrollment in a hypothetical study comparing FMT to standard antibiotic treatment. The survey was developed internally and was not validated. Questions used the Likert-scale (Survey).

Patients with CDI were identified by monitoring for positive C difficile polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stool tests and then screened for inclusion by medical record review. Inclusion criteria were (1) MVAHCS hospitalization; and (2) written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were the inability to communicate or participate in an interview. Patient responses regarding their likelihood of agreeing to FMT for CDI treatment under different circumstances were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. These circumstances included FMT for their current episode of CDI, FMT for a subsequent episode, and FMT if recommended by their physician. Possible concerns regarding FMT also were solicited, including infection risk, effectiveness, and procedural aesthetics. The MVAHCS institutional review board approved the study.

Results

Stool PCR tests for CDI were monitored for 158 days from 2013 to 2014 (based on availability of study staff), yielding 106 positive results. Of those, 31 (29%) were from outpatients and not addressed further. Of the 75 positive CDI tests from 66 hospitalized patients (9 patients had duplicate tests), 18 of 66 (27%) were not able to provide consent and were excluded, leaving 48 eligible patients. Six (13%) were missed for logistic reasons (patient at a test or procedure, discharged before approached, etc), leaving 42 patients who were approached for participation. Among these, 34 (81%) consented to participate in the survey. Two subjects (6%) found the topic so unappealing that they terminated the interview.

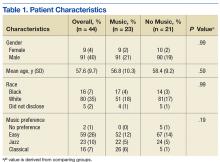

The majority of enrolled subjects were men (32/34, 94%), with a mean age of 65.3 years (range, 31-89). Eleven subjects (32%) reported a prior CDI episode, with 10 reporting 1 such episode, and the other 2 episodes. Those with prior CDI reported the effect of CDI on their overall quality of life as 5.1 (1 = no limitation, 10 = severe limitation). Respondents were fairly accurate regarding the risk of recurrence after an initial episode of CDI, with the average expectedrecurrence rate estimated at 33%. In contrast, their estimation of the risk of recurrence after a second CDI episode was lower (28%), although the risk of recurrent episodes increases with each CDI recurrence.

Regarding FMT, 5 subjects indicated awareness of the procedure: 2 learning of it from a news source, 1 from family, 1 from a health care provider, and 1 was unsure of the source. After subjects received a description of FMT, their opinions regarding the procedure were elicited. When asked which route of delivery they would prefer if they were to undergo FMT, the 33 subjects who provided a response indicated a strong preference for either enema (15, 45%) or colonoscopy (10, 30%), compared with just 4 (12%) indicating no preference, 2 (6%) choosing nasogastric tube administration, and 2 (6%) indicating that they would not undergo FMT by any route (P < .001).

Regarding the location of FMT administration (hospital setting vs self-administered at home), 31 of 33 respondents (94%) indicated they would prefer FMT to occur in the hospital vs 2 (6%) preferring self-administration at home (P < .001). The preferred source of donor stool was more evenly distributed, with 14 of 32 respondents (44%) indicating a preference for an anonymous donor, 11 preferring a family member (34%), and 7 (21%) with no preference (P = .21).

Subjects were asked about concerns regarding FMT, and asked to rate each on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all concerning; 5 = overwhelming concern). Concerns regarding risk of infection and effectiveness received an average score of 2.74 and 2.72, respectively, whereas concern regarding the aesthetics, or "yuck factor" was slightly lower (2.1: P = NS for all comparisons). Subjects also were asked to rate the likelihood of undergoing FMT, if it were available, for their current episode of CDI, a subsequent episode of CDI, or if their physician recommended undergoing FMT (10 point scale: 1 = not at all likely; 10 = certainly agree to FMT). The mean scores (SD) for agreeing to FMT for the current or a subsequent episode were 4.8 (SD 2.7) and 5.6 (SD 3.0); P = .12, but increased to 7.1 (SD 3.23) if FMT were recommended by their physician (P < .001 for FMT if physician recommended vs FMT for current episode; P = .001 for FMT if physician recommended vs FMT for a subsequent episode). Finally, subjects were asked about the likelihood of enrolling in a study comparing FMT to standard antimicrobial treatment, with answers ranging from 1 (almost certainly would not enroll) to 5 (almost certainly would enroll). Among the 32 respondents to this question, 17 (53%) answered either "probably would enroll" or "almost certainly would enroll," with a mean score of 3.2.

Discussion

Overall, VA patients with a current episode of CDI were not aware of FMT, with just 15% knowing about the procedure. However, after learning about FMT, patients expressed clear opinions regarding the route and setting of FMT administration, with enema or colonoscopy being the preferred routes, and a hospital the preferred setting. In contrast, subjects expressed ambivalence with regard to the source of donor stool, with no clear preference for stool from an anonymous donor vs from a family member.

When asked about concerns regarding FMT, none of the presented options (risk of infection, uncertain effectiveness, or procedural aesthetics) emerged as significantly more important than did others, although the oft-cited concern regarding FMT aesthetics engendered the lowest overall level of concern. In terms of FMT acceptance, 4 subjects (12%) were opposed to the procedure, indicating that they were not at all likely to agree to FMT for all scenarios (defined as a score of 1 or 2 on the 10-point Likert scale) or by terminating the survey because of the questions. However, 15 (44%) indicated that they would certainly agree to FMT (defined as a score of 9 or 10 on the 10-point Likert scale) if their physician recommended it. Physician recommendation for FMT resulted in the highest overall likelihood of agreeing to FMT, a finding in agreement with a previous survey of FMT for CDI.10 Most subjects indicated likely enrollment in a potential study comparing FMT with standard antimicrobial therapy.

Strengths/Limitations

Study strengths included surveying patients with current CDI, such that patients had personal experience with the disease in question. Use of in-person interviews also resulted in a robust response rate of 81% and allowed subjects to clarify any unclear questions with study personnel. Weaknesses included a relatively small sample size, underrepresentation of women, and lack of detail regarding respondent characteristics. Additionally, capsule delivery of FMT was not assessed since this method of delivery had not been published at the time of survey administration.

Conclusion

This survey of VA patients with CDI suggests that aesthetic concerns are not a critical deterrent for this population, and interest in FMT for the treatment of recurrent CDI exists. Physician recommendation to undergo FMT seems to be the most influential factor affecting the likelihood of agreeing to undergo FMT. These results support the feasibility of conducting clinical trials of FMT in the VA system.

Clostridium difficile (C difficile) infection (CDI) is a leading cause of infectious diarrhea among hospitalized patients and, increasingly, in ambulatory patients.1,2 The high prevalence of CDI and the high recurrence rates (15%-30%) led the CDC to categorize C difficile as an "urgent" threat (the highest category) in its 2013 Antimicrobial Resistance Threat Report.3-5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommended treatment for CDI is vancomycin or metronidazole; more recent studies also support fidaxomicin use.4,6,7

Patients experiencing recurrent CDI are at risk for further recurrences, such that after the third CDI episode, the risk of subsequent recurrences exceeds 50%.8 This recurrence rate has stimulated research into other treatments, including fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). A recent systematic review of FMT reports that 85% of patients have resolution of symptoms without recurrence after FMT, although this is based on data from case series and 2 small randomized clinical trials.9

A commonly cited barrier to FMT is patient acceptance. In response to this concern, a previous survey demonstrated that 81% of respondents would opt for FMT to treat a hypothetical case of recurrent CDI.10 However, the surveyed population did not have CDI, and the 48% response rate is concerning, since those with a favorable opinion of FMT might be more willing to complete a survey than would other patients. Accordingly, the authors systematically surveyed hospitalized veterans with active CDI to assess their knowledge, attitudes, and opinions about FMT as a treatment for CDI.

Methods

In-person patient interviews were conducted by one of the study authors at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS), consisting of 13 to 18 questions. Questions addressed any prior CDI episodes and knowledge of the following: CDI, recurrence risk, and FMT; preferred route and location of FMT administration; concerns regarding FMT; likelihood of agreeing to undergo FMT (if available); and likelihood of enrollment in a hypothetical study comparing FMT to standard antibiotic treatment. The survey was developed internally and was not validated. Questions used the Likert-scale (Survey).

Patients with CDI were identified by monitoring for positive C difficile polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stool tests and then screened for inclusion by medical record review. Inclusion criteria were (1) MVAHCS hospitalization; and (2) written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were the inability to communicate or participate in an interview. Patient responses regarding their likelihood of agreeing to FMT for CDI treatment under different circumstances were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. These circumstances included FMT for their current episode of CDI, FMT for a subsequent episode, and FMT if recommended by their physician. Possible concerns regarding FMT also were solicited, including infection risk, effectiveness, and procedural aesthetics. The MVAHCS institutional review board approved the study.

Results

Stool PCR tests for CDI were monitored for 158 days from 2013 to 2014 (based on availability of study staff), yielding 106 positive results. Of those, 31 (29%) were from outpatients and not addressed further. Of the 75 positive CDI tests from 66 hospitalized patients (9 patients had duplicate tests), 18 of 66 (27%) were not able to provide consent and were excluded, leaving 48 eligible patients. Six (13%) were missed for logistic reasons (patient at a test or procedure, discharged before approached, etc), leaving 42 patients who were approached for participation. Among these, 34 (81%) consented to participate in the survey. Two subjects (6%) found the topic so unappealing that they terminated the interview.

The majority of enrolled subjects were men (32/34, 94%), with a mean age of 65.3 years (range, 31-89). Eleven subjects (32%) reported a prior CDI episode, with 10 reporting 1 such episode, and the other 2 episodes. Those with prior CDI reported the effect of CDI on their overall quality of life as 5.1 (1 = no limitation, 10 = severe limitation). Respondents were fairly accurate regarding the risk of recurrence after an initial episode of CDI, with the average expectedrecurrence rate estimated at 33%. In contrast, their estimation of the risk of recurrence after a second CDI episode was lower (28%), although the risk of recurrent episodes increases with each CDI recurrence.

Regarding FMT, 5 subjects indicated awareness of the procedure: 2 learning of it from a news source, 1 from family, 1 from a health care provider, and 1 was unsure of the source. After subjects received a description of FMT, their opinions regarding the procedure were elicited. When asked which route of delivery they would prefer if they were to undergo FMT, the 33 subjects who provided a response indicated a strong preference for either enema (15, 45%) or colonoscopy (10, 30%), compared with just 4 (12%) indicating no preference, 2 (6%) choosing nasogastric tube administration, and 2 (6%) indicating that they would not undergo FMT by any route (P < .001).

Regarding the location of FMT administration (hospital setting vs self-administered at home), 31 of 33 respondents (94%) indicated they would prefer FMT to occur in the hospital vs 2 (6%) preferring self-administration at home (P < .001). The preferred source of donor stool was more evenly distributed, with 14 of 32 respondents (44%) indicating a preference for an anonymous donor, 11 preferring a family member (34%), and 7 (21%) with no preference (P = .21).

Subjects were asked about concerns regarding FMT, and asked to rate each on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all concerning; 5 = overwhelming concern). Concerns regarding risk of infection and effectiveness received an average score of 2.74 and 2.72, respectively, whereas concern regarding the aesthetics, or "yuck factor" was slightly lower (2.1: P = NS for all comparisons). Subjects also were asked to rate the likelihood of undergoing FMT, if it were available, for their current episode of CDI, a subsequent episode of CDI, or if their physician recommended undergoing FMT (10 point scale: 1 = not at all likely; 10 = certainly agree to FMT). The mean scores (SD) for agreeing to FMT for the current or a subsequent episode were 4.8 (SD 2.7) and 5.6 (SD 3.0); P = .12, but increased to 7.1 (SD 3.23) if FMT were recommended by their physician (P < .001 for FMT if physician recommended vs FMT for current episode; P = .001 for FMT if physician recommended vs FMT for a subsequent episode). Finally, subjects were asked about the likelihood of enrolling in a study comparing FMT to standard antimicrobial treatment, with answers ranging from 1 (almost certainly would not enroll) to 5 (almost certainly would enroll). Among the 32 respondents to this question, 17 (53%) answered either "probably would enroll" or "almost certainly would enroll," with a mean score of 3.2.

Discussion

Overall, VA patients with a current episode of CDI were not aware of FMT, with just 15% knowing about the procedure. However, after learning about FMT, patients expressed clear opinions regarding the route and setting of FMT administration, with enema or colonoscopy being the preferred routes, and a hospital the preferred setting. In contrast, subjects expressed ambivalence with regard to the source of donor stool, with no clear preference for stool from an anonymous donor vs from a family member.

When asked about concerns regarding FMT, none of the presented options (risk of infection, uncertain effectiveness, or procedural aesthetics) emerged as significantly more important than did others, although the oft-cited concern regarding FMT aesthetics engendered the lowest overall level of concern. In terms of FMT acceptance, 4 subjects (12%) were opposed to the procedure, indicating that they were not at all likely to agree to FMT for all scenarios (defined as a score of 1 or 2 on the 10-point Likert scale) or by terminating the survey because of the questions. However, 15 (44%) indicated that they would certainly agree to FMT (defined as a score of 9 or 10 on the 10-point Likert scale) if their physician recommended it. Physician recommendation for FMT resulted in the highest overall likelihood of agreeing to FMT, a finding in agreement with a previous survey of FMT for CDI.10 Most subjects indicated likely enrollment in a potential study comparing FMT with standard antimicrobial therapy.

Strengths/Limitations

Study strengths included surveying patients with current CDI, such that patients had personal experience with the disease in question. Use of in-person interviews also resulted in a robust response rate of 81% and allowed subjects to clarify any unclear questions with study personnel. Weaknesses included a relatively small sample size, underrepresentation of women, and lack of detail regarding respondent characteristics. Additionally, capsule delivery of FMT was not assessed since this method of delivery had not been published at the time of survey administration.

Conclusion

This survey of VA patients with CDI suggests that aesthetic concerns are not a critical deterrent for this population, and interest in FMT for the treatment of recurrent CDI exists. Physician recommendation to undergo FMT seems to be the most influential factor affecting the likelihood of agreeing to undergo FMT. These results support the feasibility of conducting clinical trials of FMT in the VA system.

1. Miller BA, Chen LF, Sexton DJ, Anderson DJ. Comparison of the burdens of hospital-onset, healthcare facility-associated Clostridium difficile Infection and of healthcare-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(4):387-390.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Clostridium difficile-associated disease in populations previously at low risk--four states, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(47):1201-1205.

3. Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al; Polymer Alternative for CDI Treatment (PACT) investigators. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(3):345-354.

4. Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al; OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):422-431.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013. Updated July 17, 2014. Accessed November 16.2016.

6. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

7. Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, et al; OPT-80-004 Clinical Study Group. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(4):281-289.

8. Johnson S. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a review of risk factors, treatments, and outcomes. J Infect. 2009;58(6):403-410.

9. Drekonja DM, Reich J, Gezahegn S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection--a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9):630-638.

10. Zipursky JS, Sidorsky TI, Freedman CA, Sidorsky MN, Kirkland KB. Patient attitudes toward the use of fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(12):1652-1658.

1. Miller BA, Chen LF, Sexton DJ, Anderson DJ. Comparison of the burdens of hospital-onset, healthcare facility-associated Clostridium difficile Infection and of healthcare-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(4):387-390.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Clostridium difficile-associated disease in populations previously at low risk--four states, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(47):1201-1205.

3. Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al; Polymer Alternative for CDI Treatment (PACT) investigators. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(3):345-354.

4. Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al; OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):422-431.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013. Updated July 17, 2014. Accessed November 16.2016.

6. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

7. Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, et al; OPT-80-004 Clinical Study Group. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(4):281-289.

8. Johnson S. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a review of risk factors, treatments, and outcomes. J Infect. 2009;58(6):403-410.

9. Drekonja DM, Reich J, Gezahegn S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection--a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9):630-638.

10. Zipursky JS, Sidorsky TI, Freedman CA, Sidorsky MN, Kirkland KB. Patient attitudes toward the use of fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(12):1652-1658.

Leadership Initiatives in Patient-Centered Transgender Care

Patient-centered care is of fundamental importance when caring for the transgender population due to the well-established history of social stigma and systemic discrimination. Therefore, nursing education is mandated to equip graduates with culturally competent patient-centered care skills.1 In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) launched The Future of Nursing initiative, which outlined the major role nursing should play in transforming the health care system to meet the health care needs of diverse U.S. populations.

The initiative produced a blueprint of action-focused institutional recommendations at the local, state, and national levels that would facilitate the reforms necessary to transform the U.S. health care system. One of the recommendations of the IOM report was to increase opportunities for nurses to manage and lead collaborative efforts with physicians and other health care team members in the areas of systems redesign and research, to improve practice environments and health systems.2

The VHA is the largest integrated health care system in the U.S., serving more than 8.76 million veterans at more than 1,700 facilities. The VHA has an organizational structure that uses centralized control in Washington, DC, and branches out to 18 regional networks that are divided into local facilities in 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Philippines. This type of structure is known for promoting efficient standardization of processes and procedures across an organization.3

The VHA Blueprint for Excellence envisions the promotion of a positive culture of service and the advancement of health care innovations necessary to create an environment that all veterans deserve.4 To that end, the VHA can be a promising health care institution through which patient-centered initiatives can be standardized, promulgated nationally, and replicated as a model for the country and international health systems. However, it is important to note that the bureaucratic organizational structure of the VHA's national integrated system of care is based on a systemwide standardization effort.5 Therefore, more time may be required to implement organizational changes.

Transgender populations face significant social stigmatization, discrimination, and marginalization that contribute to negative patient outcomes. Consequently, this population experiences high rates of suicide, HIV/AIDS, substance use disorder, poverty, and homelessness.6 Due to the growing evidence of health disparities and negative health outcomes affecting transgender populations, the federal government has identified transgender patient care and outcomes as a major health concern and priority in the Healthy People Initiative 2020.2,7,8

In 2012, the VHA issued a directive mandating services for transgender veterans.9 Nevertheless, health care staff significantly lack the knowledge, skills, and cultural competencies that are vital in transgender care.

This article reviews the prevalence and demographics of the transgender population, social challenges, global health concerns, and public health policies. The article also examines how the doctor of nursing practice (DNP)-prepared nurse leader can provide transformational nursing leadership to facilitate culturally competent, patient-centered initiatives to improve access and services for transgender individuals in the VHA and provide a model for change in transgender population health.

Definitions

Gender is a behavioral, cultural, or psychological trait assigned by society that is associated with male or female sex. Sex denotes the biologic differences between males and females. Transgender is an umbrella term used to describe people whose gender identity or gender expression is different from that of their sex assigned at birth. Transsexualism is a subset of transgender persons who have taken steps to self-identify or transition to look like their preferred gender.

Demographics

Estimates of the prevalence of transgenderism are roughly drawn from less rigorous methods, such as the combination of parents who report transgenderism in children, the number of adults reportedly seeking clinical care (such as cross-sex or gender-affirming hormone therapy), and the number of surgical interventions reported in different countries.10 A meta-analysis of 21 studies concluded that the ratio of transsexuals (individuals who are altering or have already altered their birth sex) was predominantly 1:14,705 adult males and 1:38,461 adult females.11 Since all transgender persons do not identify as transsexual, these figures do not provide a precise estimation of the number of transgender persons worldwide.

About 700,000, or 0.3%, of the adult population in the U.S. identify themselves as transgender, and an estimated 134,300 identify as transgender veterans.6,12 The transgender population in the U.S. is estimated to be 55% white, 16% African American, 21% Hispanic, and 8% other races.13 The U.S. census data noted that the transgender population was geographically located across the nation. Transgender persons are more likely to be single, never married, divorced, and more educated but with significantly less household income.2 Data to provide an accurate reflection of the number of transgender people in the U.S. are lacking. Some transgender individuals also may identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, making population-based estimation even more challenging and difficult.

Transgender persons who have transitioned may not have changed their names or changed their identified sex on official Social Security records, which the Social Security Administration allows only if there is evidence that genital sexual reassignment surgery was performed.14 The number of transgender adults requesting treatment continues to rise.10

Social and Health Challenges

Transgender people face many challenges because of their gender identity. Surveys assessing the living conditions of transgender people have found that 43% to 60% report high levels of physical violence.15 By comparison, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey found that interpersonal violence and sexual violence were reported by lesbian and gay individuals at equal or higher levels than that reported by heterosexuals. Forty-four percent of lesbian women, 35% of heterosexual women, 29% of heterosexual men, and 26% of gay men reported experiencing rape or physical violence.16 A study in Spain reported 59% of transgender people experienced patterns of harassment, and in Canada, 34% of transgender people lived below the poverty level.17,18

In the U.S., the National Transgender Discrimination Survey of 6,450 transgender and nonconforming participants provided extensive data on challenges experienced by transgender people.6 Discrimination was frequently experienced in accessing health care. Due to transgender status, 19% were denied care, and 28% postponed care due to perceived harassment and violence within a health care setting.6 The same study also reported that as many as 41% live in extreme poverty with incomes of less than $10,000 per year reported. Twenty-six percent were physically assaulted, and 10% experienced sexual violence. More than 25% of the transgender population misused drugs or alcohol to cope with mistreatment.6

In the U.S., HIV infection rates for transgender individuals were more than 4 times (2.64%) the rate of the general population (0.6%).6 Internationally, there is a high prevalence of HIV in transgender women. The prevalence rate of HIV in U.S. transgender women was 21.74% of the estimated U.S. adult transgender population of about 700,000.19 One in 4 people living with HIV in the U.S. are women.20

Suicide attempt rates are extremely high among transgender people. A suicide rate of 22% to 43% has been reported across Europe, Canada, and the U.S.21 Depression and anxiety were commonly noted as a result of discrimination and social stigma. In the U.S., transgender persons reported high rates of depression, with 41% reporting attempted suicide compared with 1.6% of the general population.6 Access to health care services, such as mental health, psychosocial support, and stress management are critical for this vulnerable population.22

Health Policies

Since 1994, the UK has instituted legal employment protections for the transgender population. In the UK, transgender persons, including military and prisoners, have health care coverage that includes sexual reassignment surgery as part of the UK's National Health Service.23

In the U.S., the federal policy of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" barring transgender persons from serving openly in the military was repealed in June 2016. This policy historically has had a silencing effect on perpetuating institutionalized biases.24 This remains problematic even after veterans have transitioned from military service to the VA for civilian care.

Between 2006 and 2013, the reported prevalence and incidence of transgender-related diagnoses in the VA have steadily increased with 40% of new diagnoses occurring since 2011.25 In fiscal year 2013, there were 32.9 per 100,000 veterans with transgender-related diagnoses.25 Health care staff, in particular health care providers (HCPs), can play a critical role in reducing health disparities and unequal treatment.26

With the passage of the U.S. Affordable Care Act (ACA), health insurance coverage for transgender persons is now guaranteed by law, and health disparities within the transgender population can begin to be properly addressed. The ACA offers the ability to purchase health insurance, possibly qualify for Medicaid, or obtain subsidies to purchase health insurance. Insurance coverage is accessible without regard to discrimination or preexisting conditions.27 As of May 2014, the Medicare program covered medically necessary hormone therapy and sex reassignment surgery.13 While VA benefits cover hormone therapy for transgender veterans, sex reassignment surgery is not currently a covered benefit.28 The ACA now increases access to primary care, preventative care, mental health services, and community health programs not previously available in the transgender community.

Healthy People 2020 Goals

One of the Healthy People 2020 stated goals is to improve the health and wellness of transgender people.29 The objective is to increase the number of population-based data collection systems used to monitor transgender people from the baseline of 2 to a total of 4 by 2020. The data systems would be assigned to collect relevant data, such as mental health; HIV status; illicit drug, alcohol, and tobacco use; cervical and breast cancer screening; health insurance coverage; and access to health care.

Health Care Staff Readiness

Transgender persons face health care challenges with major health disparities due to their gender identity. Transgender persons as a defined population are not well understood by HCPs. In a survey, 50% of transgender respondents reported that they had to teach their medical provider about transgender care.6 Negative perceptions of transgender persons are well established and have contribute to the poor health care access and services that transgender persons receive. Transgender persons are often denied access to care, denied visitation rights, and are hesitant to share information for fear of bureaucratic exclusion or isolation.

There is a lack of evidence-based studies to guide care and help HCPs gain greater understanding of this population's unique needs.30 Additionally, a significant lack of knowledge, skills, cultural competence, and awareness exist in providing transgender care. Research on nursing attitudes concerning transgender care consistently found negative attitudes, and physicians also frequently reported witnessing derogatory comments and discriminatory care from colleagues.31,32 The study by Carabez and colleagues found that practicing nurses rarely received the proper education or training in transgender health issues, and many were unaware of the needs of this population.33 In addition, many HCPs were uncomfortable working with transgender patients. Physicians also expressed knowledge deficits on gender identity disorders due to a lack of training and ethical concerns about their roles in providing gender-transitioning treatment.26

Although the VHA directive states that transgender services and treatment should be standardized, the VHA has not approved, defined, or endorsed specific standards of care or clinical guidelines within the organization for transgender care, further heightening HCP concerns.9 The clinical practice guidelines available for addressing preventive care for transgender patients are primarily based on consensus of expert opinion.34 Expert opinion has produced the Standards of Care (SOC) for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and cited by the IOM as the major clinical practice guidelines for providing care to transgender individuals.2 Transgender care at the VHA is guided by the WPATH standards of care.35

The VHA has created national educational programs and policies with targeted goals to provide uniform, culturally competent, patient-centered care. Online transgender health presentations are available, and at least 15 VHA facilities have transgender support groups.30 While the VHA supports a patient-centered philosophy for transgender patient care, many facilities do not currently have organizational initiatives that enhance clinical preparation of HCPs or have sufficiently modified the environment to better accommodate the health care needs of transgender veterans.

DNP Preparation

The DNP terminal degree provides nurses with doctoral-level training in organizational and systems leadership, leading quality improvement, and implementing systemwide initiatives by using scientific findings to drive processes that improve quality of care for a changing patient population.36 Preparation in research analysis of evidence-based interventions also is essential to evaluating practice patterns, patient outcomes, and systems of care that can identify gaps in practice. Training in health care policy and advocacy, information systems, patient care technology, and population health also is provided so that DNPs are competent to develop system strategies to transform health care through clinical prevention and health promotion.

QSEN Framework

In keeping with the IOM's Future of Nursing initiative recommendations that graduate nurses be prepared as leaders in education, practice, administration, and research, there is an increasing focus on providing graduate-level nursing education and training to ensure quality and efficiency of health outcomes.37 The Quality and Safety Education in Nursing (QSEN) project, initiated at the RWJF by Linda Cronenwett, PhD, RN, identifies a framework for knowledge, skills, and attitudes that defines the competencies that nurses need to deliver effective care to improve quality and safety within health care systems.38 These core competencies include quality improvement, safety, teamwork and collaboration, patient-centered care, evidence-based practice, and informatics. The RWJF and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing later expanded the project initiative to prepare nursing faculty to teach the QSEN competencies in graduate nursing programs.36

The DNP nurse leader is ideally suited to manage this project by applying competencies from the QSEN framework. Using open communication and mutual respect, the nurse leader is poised to effectively develop interprofessional teams to collaborate and initiate transformational changes that improve quality and patient-centered care delivered within the health care organization.

Public Health Resources

Public health resources addressing transgender patient care advocacy, public policy, community education, standards of care, cultural competency, mental health, hormone therapy, surgical interventions, reproductive health, primary care, preventative care, and research are available. For example, WPATH is an international multidisciplinary organization that has published comprehensive SOC for transgender, transsexual, and gender-nonconforming people. The seventh version of the SOC contains evidence-based guidelines for treatment.39 Additional online resources for transgender health are available from the CDC, the Center of Excellence for Transgender Health at the University of California, San Francisco; Department of Family and Community Medicine; and the National Center for Transgender Equality.13,40,41

Patient-Centered Transgender Care

The QSEN framework outlines competencies that provide applicable solutions that help prepare organizations to deliver culturally competent, patient-centered transgender care. The first step to creating patient-centered transgender care is to "analyze factors that create barriers to patient-centered care."42 The magnitude of the barriers to providing patient-centered transgender care also must be identified and understood. An assessment of individual values, beliefs, and attitudes can help to identify cultural characteristics and eliminate stereotypes that impact health practices.43

The nurse leader should solicit support from stakeholders to assess barriers to providing patient-centered transgender care at the system level. Stakeholders would include staff directly involved in patient care, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, registered nurses, nurse managers, nurse educators, licensed practical nurses, medical support assistants, psychologists, dieticians, and social workers. Other ancillary stakeholders with an interest in creating a patient-centered environment with positive patient outcomes include the executive leadership team of the organization, which consists of the chief of staff, director, administrative officers, and nurse executive.

The nurse leader should consult with experts in transgender care and present evidence-based research showing how deficits in staff knowledge, skills, and cultural competence negatively impact the quality of care provided to transgender persons. National data on the consequential health disparities and negative impacts on patient outcomes also should be discussed and presented to all stakeholders. The nurse leader in collaboration with the VA Office of Research and Development is ideally suited to obtain institutional review board approval of a proposal to conduct a needs assessment survey of health care staff barriers to providing patient-centered transgender care. Thereafter, the nurse leader would analyze, extract, and synthesize the data and evaluate the resources and technology available to translate this research knowledge into a clinical practice setting at the system level.44

The second solution uses the results of the survey to develop staff competency training within the organization. The nurse leader can facilitate collaboration and team building to develop practice guidelines and SOC. Competency training will prepare the staff to assist in developing strategies to improve the quality of care for transgender persons. Educationconcerning existing evidence-based clinical guidelines and SOC as well as anecdotal evidence of the needs of transgender patients should be included in competency training.45 One approach to competency training would be to trainintegrated multidisciplinary teams with expertise in transgender care to promote wellness and disease prevention.9 The nurse leader should collaborate with multiple disciplines to facilitate the development of interdisciplinary teams from nursing, medicine, social work, pharmacy, primary care, mental health, women's health, and endocrinology to participate in the Specialty Care Access Network Extension of Community Healthcare outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) training. Training can be offered by videoconferencing over several months and provides cost-effective, efficient training of providers in patient-centered transgender care.46,47 After the SCAN-ECHO program is completed, trained nursing experts could then develop a cultural sensitivity training program for nursing organizations to be offered to educate health care staff on an annual basis.

The third solution addresses the QSEN competency to "Analyze institutional features of the facilities that support or pose barriers to patient-centered care."42 Many veterans do not perceive VA environments as welcoming. In a study by Sherman and colleagues, less than one-third of veterans believed the VA environment was welcoming to sexual or gender minorities, and sexual orientation or gender identity was disclosed by only about 25% of veterans.48 Many veterans in this study felt uncomfortable disclosing their gender or sexual orientation. The majority felt that providers should not routinely ask about sexual orientation or gender identity, and 24% said they were very or somewhat uncomfortable discussing the issue. In another study, 202 VA providers were asked if they viewed the VA as welcoming, and 32% said the VA was somewhat or very unwelcoming.48

The nurse leader is trained in the essentials of health care policy advocacy, which is central to nursing practice.49 Nursing as a profession values social justice and equality, which are linked to fewer health disparities and more stable health indicators.50 Therefore, nursing can ideally provide organizational leaders by developing a culture wherein stable, patient-centered relationships can develop and thrive.

Organizational Culture

Strategies must be deployed to create an organizational culture that is welcoming, respectful, and supportive of transgender patients and family preferences. VA should develop support groups for transgender veterans in VA facilities. Support groups are helpful in diminishing stress, improving self-esteem, building confidence, and improving social relationships.51 Additionally, VA should develop community-based partnerships with other organizations that already provide institutional care and support from HCPs who support transgender persons' right to self-determination.52 These partnerships can foster environmental influences over time and lead to the development of trusting relationships between transgender veterans and the VA organization.

Another community partnership of importance for the nurse leader to develop is an alliance with local universities to train nursing students in cultural competencies in transgender care at VA facilities. The U.S. population continues to diversify in race and ethnicity and cultural influences; therefore, nurses must be prepared in cultural competencies in order to provide quality care that reduces health disparities.53

Under federal law, the VHA has a data sharing agreement with the DoD. Despite the repeal of the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" federal law, which cleared the way for transgender persons to openly serve in the military, many transgender persons may remain fearful of reprisals, such as judgment, denial of care, or loss of benefits if gender identity is disclosed.54 Given the bureaucratic structure of the VHA, the implementation of cultural changes at the system level will require a collaborative effort between multidisciplinary teams and community partnerships to transform the VA environment over time. The authors believe that on this issue, external forces must guide and lead changes within the VA system in order to develop sustainable and trusting relationships with transgender veterans.

The fourth solution is implementation of policies that "empower patients or families in all aspects of the health care process."42 Again, the nurse leader is trained and prepared to advocate for a policy that implements a Patient Bill of Rights that explicitly guarantees health care and prohibits discrimination of gender-minority veterans. This change would foster trust and confidence from transgender individuals. A study found that 83% of providers and 83% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender veterans believe that this policy change would make the VHA environment more welcoming.48 Providing transgender-affirming materials and language on standard forms also would eliminate barriers, promote patient-centered care, and empower transgender patients by creating an environment that is more inclusive of everyone.48

Conclusion

The nurse leader is well positioned to implement the QSEN framework to integrate research, practice, and policy to create a more inclusive, patient-centered health care system for transgender veterans. By using the essential principles of doctoral education for advanced nursing practice, the nurse leader is prepared to advocate for changing the organization at the systems level. The nurse leader also is equipped to direct the implementation of patient-centered transgender care initiatives by ensuring the integration of the nursing organization as a partner in strategic planning as well as the development of solutions.

The VHA Blueprint of Excellence envisions organization and collaboration to promote new relationships that serve and benefit veterans. The DNP preparation allows the nurse leader to demonstrate the ability to collaborate with VHA stakeholders and develop alliances within and outside the organization by advocating for policy changes that will be transformational in improving health care delivery and patient outcomes to vulnerable transgender veteran populations. The IOM has tasked nurse executives with creating a health care infrastructure of doctorally prepared nurses to provide patient care that is increasingly growing more complex. With an increasing number of veterans using services, VHA has prioritized an expansion in the number of doctorally prepared nurses.55

As the largest integrated health care system in the U.S., the VHA provides an ideal setting for initiating these organizational changes as a result of having developed an integrated infrastructure to collect evidence-based data at the regional (network) and state facilities and make comparisons with national benchmarks. Therefore, changes are less difficult to disseminate throughout the hierarchy of the VHA. Consequently, the VHA has been a leader in the U.S. for equity in the health care arena and provides a model for international health care systems. Finally, these changes address an urgent need to reduce health disparities, morbidity, and mortality by improving quality care and health care delivery to a vulnerable transgender population.

1. Greiner AC, Knebel E, eds. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

2. Institute of Medicine. Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2011.

3. Mintzberg H. The structuring of organizations: a synthesis of the research. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1496182 1979. Posted November 4, 2009. Accessed November 30, 2016.

4. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA blue print for excellence. https://www.va.gov/health/docs/VHA_Blueprint_for_Excellence.pdf. Published September 21, 2014. Accessed November 30, 2016.

5. Morgan RO, Teal CR, Reddy SG, Ford ME, Ashton CM. Measurement in Veterans Affairs Health Services Research: veterans as a special population. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5, part 2):1573-1583.

6. Grant JM, Mottet L, Tanis JE, Harrison J, Herman J, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads /reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed November 30, 2016.

7. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objec tives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender -health. Updated November 16, 2016. Accessed November 16, 2016.

8. Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2011.

9. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 2013-003: Providing Health Care for Transgender and Intersex Veterans. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2013.

10. Zucker KJ, Lawrence AA. Epidemiology of gender identity disorder: recommendations for the Standards of Care of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Int J Transgenderism. 2009;11(1):8-18.

11. Arcelus J, Bouman WP, Van Den Noortgate W, Claes L, Witcomb G, Fernandez-Aranda F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies in transsexualism. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(6):807-815.