User login

‘Difficult Patient’: Stigmatizing Words and Medical Error

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When I was doing my nephrology training, I had an attending who would write notes that were, well, kind of funny. I remember one time we were seeing a patient whose first name was “Lucky.” He dryly opened his section of the consult note as follows: “This is a 56-year-old woman with an ironic name who presents with acute renal failure.”

As an exhausted renal fellow, I appreciated the bit of color amid the ongoing series of tragedies that was the consult service. But let’s be clear — writing like this in the medical record is not a good idea. It wasn’t a good idea then, when any record might end up disclosed during a malpractice suit, and it’s really not a good idea now, when patients have ready and automated access to all the notes we write about them.

And yet, worse language than that of my attending appears in hospital notes all the time; there is research about this. Specifically, I’m talking about language that does not have high clinical utility but telegraphs the biases of the person writing the note. This is known as “stigmatizing language” and it can be overt or subtle.

For example, a physician wrote “I listed several fictitious medication names and she reported she was taking them.”

This casts suspicions about the patient’s credibility, as does the more subtle statement, “he claims nicotine patches don’t work for him.” Stigmatizing language may cast the patient in a difficult light, like this note: “she persevered on the fact that ... ‘you wouldn’t understand.’ ”

Stay with me.

We are going to start by defining a very sick patient population: those admitted to the hospital and who, within 48 hours, have either been transferred to the intensive care unit or died. Because of the severity of illness in this population we’ve just defined, figuring out whether a diagnostic or other error was made would be extremely high yield; these can mean the difference between life and death.

In a letter appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers examined a group of more than 2300 patients just like this from 29 hospitals, scouring the medical records for evidence of these types of errors.

Nearly one in four (23.2%) had at least one diagnostic error, which could include a missed physical exam finding, failure to ask a key question on history taking, inadequate testing, and so on.

Understanding why we make these errors is clearly critical to improving care for these patients. The researchers hypothesized that stigmatizing language might lead to errors like this. For example, by demonstrating that you don’t find a patient credible, you may ignore statements that would help make a better diagnosis.

Just over 5% of these patients had evidence of stigmatizing language in their medical notes. Like earlier studies, this language was more common if the patient was Black or had unstable housing.

Critically, stigmatizing language was more likely to be found among those who had diagnostic errors — a rate of 8.2% vs 4.1%. After adjustment for factors like race, the presence of stigmatizing language was associated with roughly a doubling of the risk for diagnostic errors.

Now, I’m all for eliminating stigmatizing language from our medical notes. And, given the increased transparency of all medical notes these days, I expect that we’ll see less of this over time. But of course, the fact that a physician doesn’t write something that disparages the patient does not necessarily mean that they don’t retain that bias. That said, those comments have an effect on all the other team members who care for that patient as well; it sets a tone and can entrench an individual’s bias more broadly. We should strive to eliminate our biases when it comes to caring for patients. But perhaps the second best thing is to work to keep those biases to ourselves.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When I was doing my nephrology training, I had an attending who would write notes that were, well, kind of funny. I remember one time we were seeing a patient whose first name was “Lucky.” He dryly opened his section of the consult note as follows: “This is a 56-year-old woman with an ironic name who presents with acute renal failure.”

As an exhausted renal fellow, I appreciated the bit of color amid the ongoing series of tragedies that was the consult service. But let’s be clear — writing like this in the medical record is not a good idea. It wasn’t a good idea then, when any record might end up disclosed during a malpractice suit, and it’s really not a good idea now, when patients have ready and automated access to all the notes we write about them.

And yet, worse language than that of my attending appears in hospital notes all the time; there is research about this. Specifically, I’m talking about language that does not have high clinical utility but telegraphs the biases of the person writing the note. This is known as “stigmatizing language” and it can be overt or subtle.

For example, a physician wrote “I listed several fictitious medication names and she reported she was taking them.”

This casts suspicions about the patient’s credibility, as does the more subtle statement, “he claims nicotine patches don’t work for him.” Stigmatizing language may cast the patient in a difficult light, like this note: “she persevered on the fact that ... ‘you wouldn’t understand.’ ”

Stay with me.

We are going to start by defining a very sick patient population: those admitted to the hospital and who, within 48 hours, have either been transferred to the intensive care unit or died. Because of the severity of illness in this population we’ve just defined, figuring out whether a diagnostic or other error was made would be extremely high yield; these can mean the difference between life and death.

In a letter appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers examined a group of more than 2300 patients just like this from 29 hospitals, scouring the medical records for evidence of these types of errors.

Nearly one in four (23.2%) had at least one diagnostic error, which could include a missed physical exam finding, failure to ask a key question on history taking, inadequate testing, and so on.

Understanding why we make these errors is clearly critical to improving care for these patients. The researchers hypothesized that stigmatizing language might lead to errors like this. For example, by demonstrating that you don’t find a patient credible, you may ignore statements that would help make a better diagnosis.

Just over 5% of these patients had evidence of stigmatizing language in their medical notes. Like earlier studies, this language was more common if the patient was Black or had unstable housing.

Critically, stigmatizing language was more likely to be found among those who had diagnostic errors — a rate of 8.2% vs 4.1%. After adjustment for factors like race, the presence of stigmatizing language was associated with roughly a doubling of the risk for diagnostic errors.

Now, I’m all for eliminating stigmatizing language from our medical notes. And, given the increased transparency of all medical notes these days, I expect that we’ll see less of this over time. But of course, the fact that a physician doesn’t write something that disparages the patient does not necessarily mean that they don’t retain that bias. That said, those comments have an effect on all the other team members who care for that patient as well; it sets a tone and can entrench an individual’s bias more broadly. We should strive to eliminate our biases when it comes to caring for patients. But perhaps the second best thing is to work to keep those biases to ourselves.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When I was doing my nephrology training, I had an attending who would write notes that were, well, kind of funny. I remember one time we were seeing a patient whose first name was “Lucky.” He dryly opened his section of the consult note as follows: “This is a 56-year-old woman with an ironic name who presents with acute renal failure.”

As an exhausted renal fellow, I appreciated the bit of color amid the ongoing series of tragedies that was the consult service. But let’s be clear — writing like this in the medical record is not a good idea. It wasn’t a good idea then, when any record might end up disclosed during a malpractice suit, and it’s really not a good idea now, when patients have ready and automated access to all the notes we write about them.

And yet, worse language than that of my attending appears in hospital notes all the time; there is research about this. Specifically, I’m talking about language that does not have high clinical utility but telegraphs the biases of the person writing the note. This is known as “stigmatizing language” and it can be overt or subtle.

For example, a physician wrote “I listed several fictitious medication names and she reported she was taking them.”

This casts suspicions about the patient’s credibility, as does the more subtle statement, “he claims nicotine patches don’t work for him.” Stigmatizing language may cast the patient in a difficult light, like this note: “she persevered on the fact that ... ‘you wouldn’t understand.’ ”

Stay with me.

We are going to start by defining a very sick patient population: those admitted to the hospital and who, within 48 hours, have either been transferred to the intensive care unit or died. Because of the severity of illness in this population we’ve just defined, figuring out whether a diagnostic or other error was made would be extremely high yield; these can mean the difference between life and death.

In a letter appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers examined a group of more than 2300 patients just like this from 29 hospitals, scouring the medical records for evidence of these types of errors.

Nearly one in four (23.2%) had at least one diagnostic error, which could include a missed physical exam finding, failure to ask a key question on history taking, inadequate testing, and so on.

Understanding why we make these errors is clearly critical to improving care for these patients. The researchers hypothesized that stigmatizing language might lead to errors like this. For example, by demonstrating that you don’t find a patient credible, you may ignore statements that would help make a better diagnosis.

Just over 5% of these patients had evidence of stigmatizing language in their medical notes. Like earlier studies, this language was more common if the patient was Black or had unstable housing.

Critically, stigmatizing language was more likely to be found among those who had diagnostic errors — a rate of 8.2% vs 4.1%. After adjustment for factors like race, the presence of stigmatizing language was associated with roughly a doubling of the risk for diagnostic errors.

Now, I’m all for eliminating stigmatizing language from our medical notes. And, given the increased transparency of all medical notes these days, I expect that we’ll see less of this over time. But of course, the fact that a physician doesn’t write something that disparages the patient does not necessarily mean that they don’t retain that bias. That said, those comments have an effect on all the other team members who care for that patient as well; it sets a tone and can entrench an individual’s bias more broadly. We should strive to eliminate our biases when it comes to caring for patients. But perhaps the second best thing is to work to keep those biases to ourselves.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A Banned Chemical That Is Still Causing Cancer

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

These types of stories usually end with a call for regulation — to ban said chemical or substance, or to regulate it — but in this case, that has already happened. This new carcinogen I’m telling you about is actually an old chemical. And it has not been manufactured or legally imported in the US since 2013.

So, why bother? Because in this case, the chemical — or, really, a group of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) — are still around: in our soil, in our food, and in our blood.

PBDEs are a group of compounds that confer flame-retardant properties to plastics, and they were used extensively in the latter part of the 20th century in electronic enclosures, business equipment, and foam cushioning in upholstery.

But there was a problem. They don’t chemically bond to plastics; they are just sort of mixed in, which means they can leach out. They are hydrophobic, meaning they don’t get washed out of soil, and, when ingested or inhaled by humans, they dissolve in our fat stores, making it difficult for our normal excretory systems to excrete them.

PBDEs biomagnify. Small animals can take them up from contaminated soil or water, and those animals are eaten by larger animals, which accumulate higher concentrations of the chemicals. This bioaccumulation increases as you move up the food web until you get to an apex predator — like you and me.

This is true of lots of chemicals, of course. The concern arises when these chemicals are toxic. To date, the toxicity data for PBDEs were pretty limited. There were some animal studies where rats were exposed to extremely high doses and they developed liver lesions — but I am always very wary of extrapolating high-dose rat toxicity studies to humans. There was also some suggestion that the chemicals could be endocrine disruptors, affecting breast and thyroid tissue.

What about cancer? In 2016, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded there was “inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogencity of” PBDEs.

In the same report, though, they suggested PBDEs are “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on mechanistic studies.

In other words, we can’t prove they’re cancerous — but come on, they probably are.

Finally, we have some evidence that really pushes us toward the carcinogenic conclusion, in the form of this study, appearing in JAMA Network Open. It’s a nice bit of epidemiology leveraging the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Researchers measured PBDE levels in blood samples from 1100 people enrolled in NHANES in 2003 and 2004 and linked them to death records collected over the next 20 years or so.

The first thing to note is that the researchers were able to measure PBDEs in the blood samples. They were in there. They were detectable. And they were variable. Dividing the 1100 participants into low, medium, and high PBDE tertiles, you can see a nearly 10-fold difference across the population.

Importantly, not many baseline variables correlated with PBDE levels. People in the highest group were a bit younger but had a fairly similar sex distribution, race, ethnicity, education, income, physical activity, smoking status, and body mass index.

This is not a randomized trial, of course — but at least based on these data, exposure levels do seem fairly random, which is what you would expect from an environmental toxin that percolates up through the food chain. They are often somewhat indiscriminate.

This similarity in baseline characteristics between people with low or high blood levels of PBDE also allows us to make some stronger inferences about the observed outcomes. Let’s take a look at them.

After adjustment for baseline factors, individuals in the highest PBDE group had a 43% higher rate of death from any cause over the follow-up period. This was not enough to achieve statistical significance, but it was close.

But the key finding is deaths due to cancer. After adjustment, cancer deaths occurred four times as frequently among those in the high PBDE group, and that is a statistically significant difference.

To be fair, cancer deaths were rare in this cohort. The vast majority of people did not die of anything during the follow-up period regardless of PBDE level. But the data are strongly suggestive of the carcinogenicity of these chemicals.

I should also point out that the researchers are linking the PBDE level at a single time point to all these future events. If PBDE levels remain relatively stable within an individual over time, that’s fine, but if they tend to vary with intake of different foods for example, this would not be captured and would actually lead to an underestimation of the cancer risk.

The researchers also didn’t have granular enough data to determine the type of cancer, but they do show that rates are similar between men and women, which might point away from the more sex-specific cancer etiologies. Clearly, some more work is needed.

Of course, I started this piece by telling you that these chemicals are already pretty much banned in the United States. What are we supposed to do about these findings? Studies have examined the primary ongoing sources of PBDE in our environment and it seems like most of our exposure will be coming from the food we eat due to that biomagnification thing: high-fat fish, meat and dairy products, and fish oil supplements. It may be worth some investigation into the relative adulteration of these products with this new old carcinogen.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

These types of stories usually end with a call for regulation — to ban said chemical or substance, or to regulate it — but in this case, that has already happened. This new carcinogen I’m telling you about is actually an old chemical. And it has not been manufactured or legally imported in the US since 2013.

So, why bother? Because in this case, the chemical — or, really, a group of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) — are still around: in our soil, in our food, and in our blood.

PBDEs are a group of compounds that confer flame-retardant properties to plastics, and they were used extensively in the latter part of the 20th century in electronic enclosures, business equipment, and foam cushioning in upholstery.

But there was a problem. They don’t chemically bond to plastics; they are just sort of mixed in, which means they can leach out. They are hydrophobic, meaning they don’t get washed out of soil, and, when ingested or inhaled by humans, they dissolve in our fat stores, making it difficult for our normal excretory systems to excrete them.

PBDEs biomagnify. Small animals can take them up from contaminated soil or water, and those animals are eaten by larger animals, which accumulate higher concentrations of the chemicals. This bioaccumulation increases as you move up the food web until you get to an apex predator — like you and me.

This is true of lots of chemicals, of course. The concern arises when these chemicals are toxic. To date, the toxicity data for PBDEs were pretty limited. There were some animal studies where rats were exposed to extremely high doses and they developed liver lesions — but I am always very wary of extrapolating high-dose rat toxicity studies to humans. There was also some suggestion that the chemicals could be endocrine disruptors, affecting breast and thyroid tissue.

What about cancer? In 2016, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded there was “inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogencity of” PBDEs.

In the same report, though, they suggested PBDEs are “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on mechanistic studies.

In other words, we can’t prove they’re cancerous — but come on, they probably are.

Finally, we have some evidence that really pushes us toward the carcinogenic conclusion, in the form of this study, appearing in JAMA Network Open. It’s a nice bit of epidemiology leveraging the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Researchers measured PBDE levels in blood samples from 1100 people enrolled in NHANES in 2003 and 2004 and linked them to death records collected over the next 20 years or so.

The first thing to note is that the researchers were able to measure PBDEs in the blood samples. They were in there. They were detectable. And they were variable. Dividing the 1100 participants into low, medium, and high PBDE tertiles, you can see a nearly 10-fold difference across the population.

Importantly, not many baseline variables correlated with PBDE levels. People in the highest group were a bit younger but had a fairly similar sex distribution, race, ethnicity, education, income, physical activity, smoking status, and body mass index.

This is not a randomized trial, of course — but at least based on these data, exposure levels do seem fairly random, which is what you would expect from an environmental toxin that percolates up through the food chain. They are often somewhat indiscriminate.

This similarity in baseline characteristics between people with low or high blood levels of PBDE also allows us to make some stronger inferences about the observed outcomes. Let’s take a look at them.

After adjustment for baseline factors, individuals in the highest PBDE group had a 43% higher rate of death from any cause over the follow-up period. This was not enough to achieve statistical significance, but it was close.

But the key finding is deaths due to cancer. After adjustment, cancer deaths occurred four times as frequently among those in the high PBDE group, and that is a statistically significant difference.

To be fair, cancer deaths were rare in this cohort. The vast majority of people did not die of anything during the follow-up period regardless of PBDE level. But the data are strongly suggestive of the carcinogenicity of these chemicals.

I should also point out that the researchers are linking the PBDE level at a single time point to all these future events. If PBDE levels remain relatively stable within an individual over time, that’s fine, but if they tend to vary with intake of different foods for example, this would not be captured and would actually lead to an underestimation of the cancer risk.

The researchers also didn’t have granular enough data to determine the type of cancer, but they do show that rates are similar between men and women, which might point away from the more sex-specific cancer etiologies. Clearly, some more work is needed.

Of course, I started this piece by telling you that these chemicals are already pretty much banned in the United States. What are we supposed to do about these findings? Studies have examined the primary ongoing sources of PBDE in our environment and it seems like most of our exposure will be coming from the food we eat due to that biomagnification thing: high-fat fish, meat and dairy products, and fish oil supplements. It may be worth some investigation into the relative adulteration of these products with this new old carcinogen.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

These types of stories usually end with a call for regulation — to ban said chemical or substance, or to regulate it — but in this case, that has already happened. This new carcinogen I’m telling you about is actually an old chemical. And it has not been manufactured or legally imported in the US since 2013.

So, why bother? Because in this case, the chemical — or, really, a group of chemicals called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) — are still around: in our soil, in our food, and in our blood.

PBDEs are a group of compounds that confer flame-retardant properties to plastics, and they were used extensively in the latter part of the 20th century in electronic enclosures, business equipment, and foam cushioning in upholstery.

But there was a problem. They don’t chemically bond to plastics; they are just sort of mixed in, which means they can leach out. They are hydrophobic, meaning they don’t get washed out of soil, and, when ingested or inhaled by humans, they dissolve in our fat stores, making it difficult for our normal excretory systems to excrete them.

PBDEs biomagnify. Small animals can take them up from contaminated soil or water, and those animals are eaten by larger animals, which accumulate higher concentrations of the chemicals. This bioaccumulation increases as you move up the food web until you get to an apex predator — like you and me.

This is true of lots of chemicals, of course. The concern arises when these chemicals are toxic. To date, the toxicity data for PBDEs were pretty limited. There were some animal studies where rats were exposed to extremely high doses and they developed liver lesions — but I am always very wary of extrapolating high-dose rat toxicity studies to humans. There was also some suggestion that the chemicals could be endocrine disruptors, affecting breast and thyroid tissue.

What about cancer? In 2016, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded there was “inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogencity of” PBDEs.

In the same report, though, they suggested PBDEs are “probably carcinogenic to humans” based on mechanistic studies.

In other words, we can’t prove they’re cancerous — but come on, they probably are.

Finally, we have some evidence that really pushes us toward the carcinogenic conclusion, in the form of this study, appearing in JAMA Network Open. It’s a nice bit of epidemiology leveraging the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Researchers measured PBDE levels in blood samples from 1100 people enrolled in NHANES in 2003 and 2004 and linked them to death records collected over the next 20 years or so.

The first thing to note is that the researchers were able to measure PBDEs in the blood samples. They were in there. They were detectable. And they were variable. Dividing the 1100 participants into low, medium, and high PBDE tertiles, you can see a nearly 10-fold difference across the population.

Importantly, not many baseline variables correlated with PBDE levels. People in the highest group were a bit younger but had a fairly similar sex distribution, race, ethnicity, education, income, physical activity, smoking status, and body mass index.

This is not a randomized trial, of course — but at least based on these data, exposure levels do seem fairly random, which is what you would expect from an environmental toxin that percolates up through the food chain. They are often somewhat indiscriminate.

This similarity in baseline characteristics between people with low or high blood levels of PBDE also allows us to make some stronger inferences about the observed outcomes. Let’s take a look at them.

After adjustment for baseline factors, individuals in the highest PBDE group had a 43% higher rate of death from any cause over the follow-up period. This was not enough to achieve statistical significance, but it was close.

But the key finding is deaths due to cancer. After adjustment, cancer deaths occurred four times as frequently among those in the high PBDE group, and that is a statistically significant difference.

To be fair, cancer deaths were rare in this cohort. The vast majority of people did not die of anything during the follow-up period regardless of PBDE level. But the data are strongly suggestive of the carcinogenicity of these chemicals.

I should also point out that the researchers are linking the PBDE level at a single time point to all these future events. If PBDE levels remain relatively stable within an individual over time, that’s fine, but if they tend to vary with intake of different foods for example, this would not be captured and would actually lead to an underestimation of the cancer risk.

The researchers also didn’t have granular enough data to determine the type of cancer, but they do show that rates are similar between men and women, which might point away from the more sex-specific cancer etiologies. Clearly, some more work is needed.

Of course, I started this piece by telling you that these chemicals are already pretty much banned in the United States. What are we supposed to do about these findings? Studies have examined the primary ongoing sources of PBDE in our environment and it seems like most of our exposure will be coming from the food we eat due to that biomagnification thing: high-fat fish, meat and dairy products, and fish oil supplements. It may be worth some investigation into the relative adulteration of these products with this new old carcinogen.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D Supplements May Be a Double-Edged Sword

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

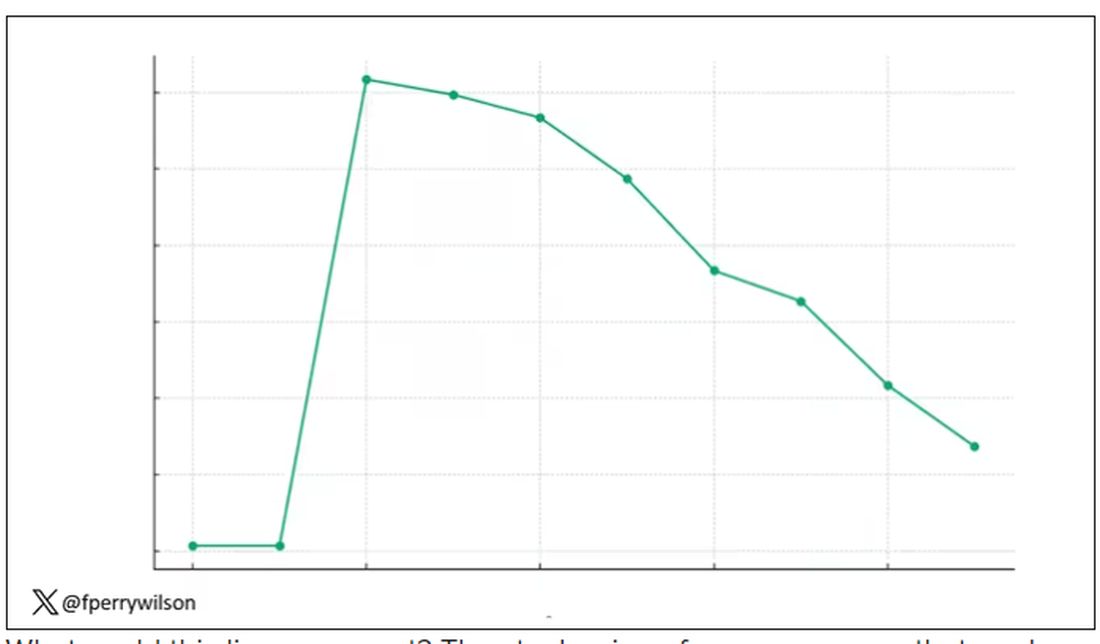

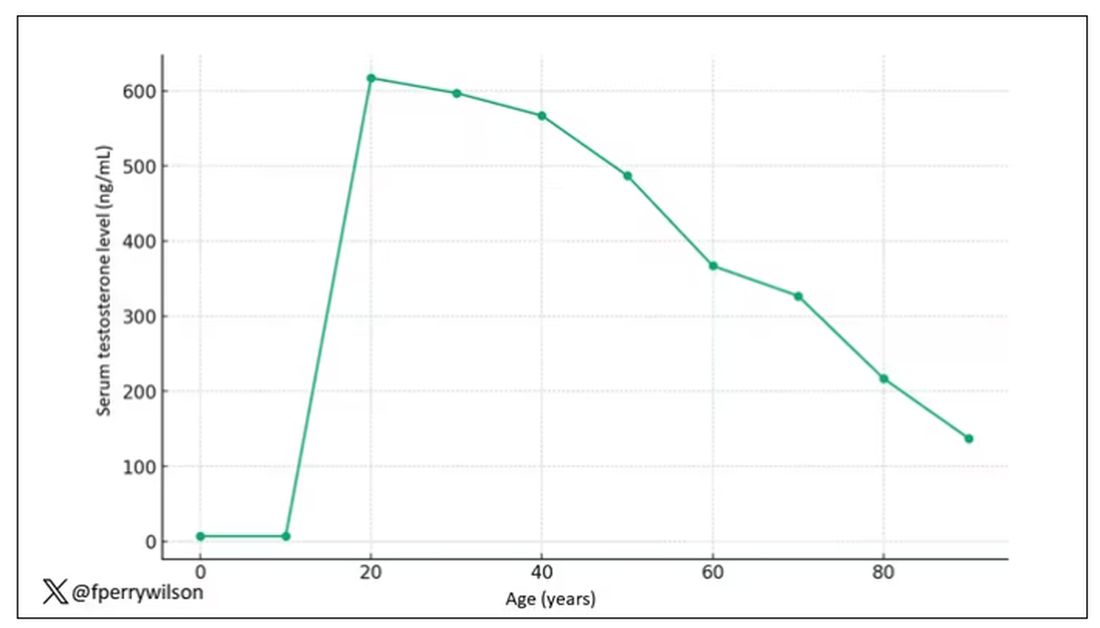

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

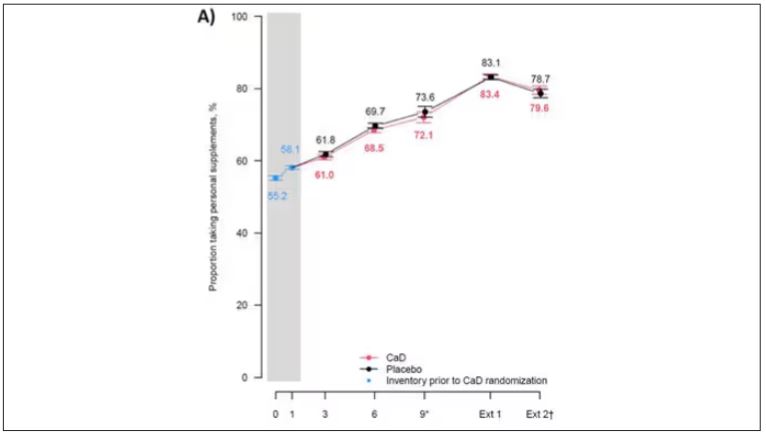

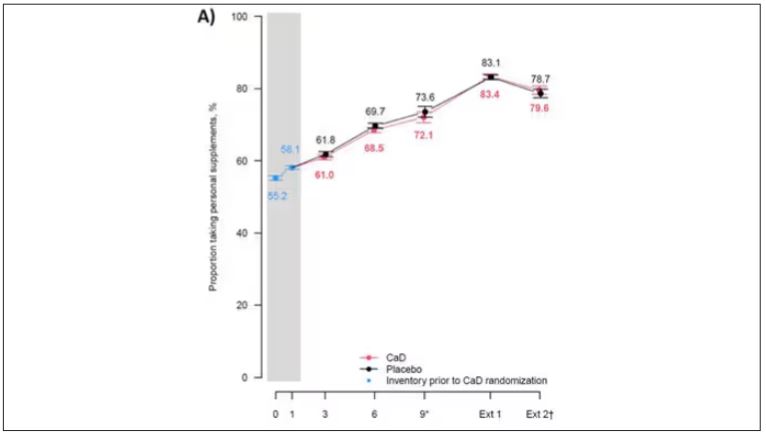

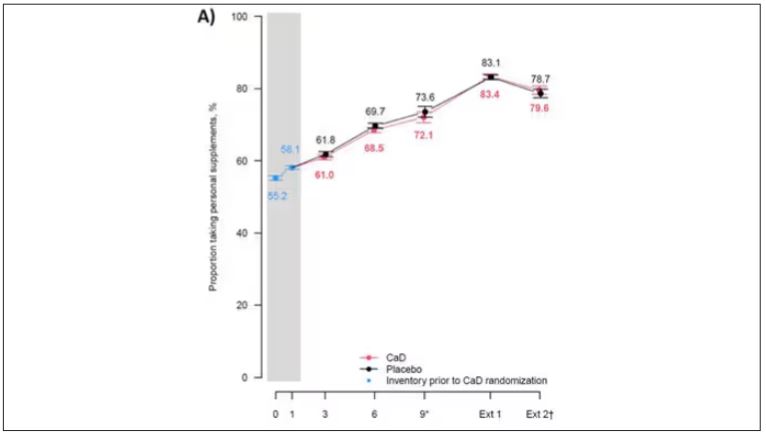

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.

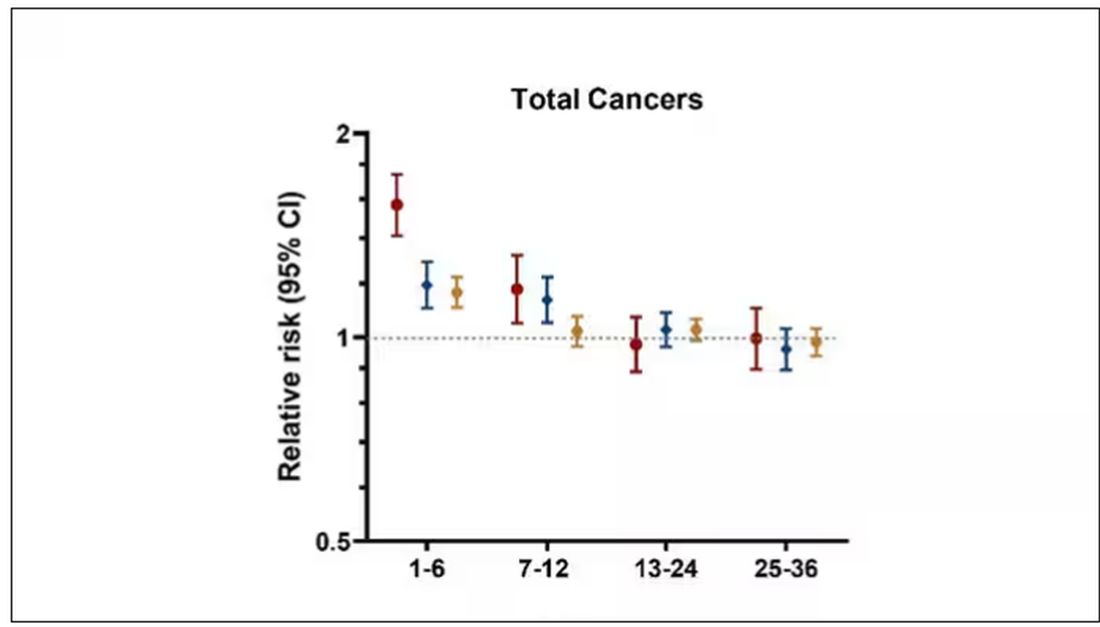

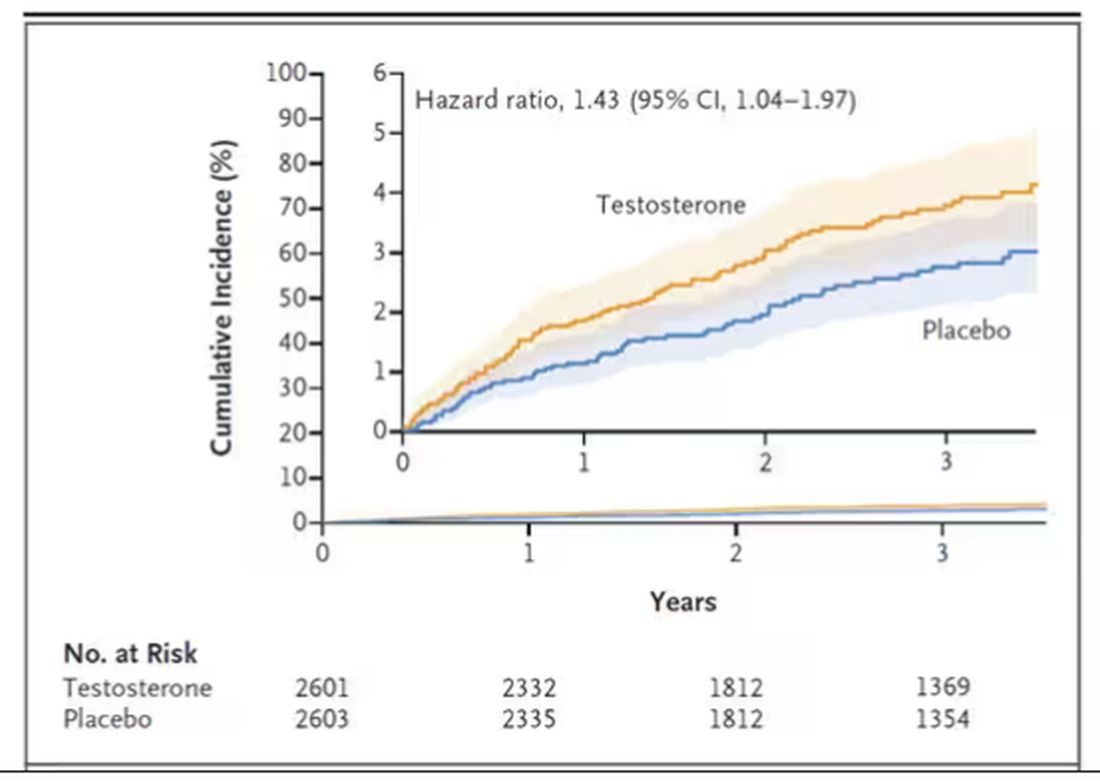

The randomized trial itself only lasted 7 years. What we are seeing in this analysis of 36,282 women is outcomes that happened at any time from randomization to the end of 2023 — around 20 years after the randomization to supplementation stopped. But, the researchers would argue, that’s probably okay. Cancer and heart disease take time to develop; we see lung cancer long after people stop smoking. So a history of consistent vitamin D supplementation may indeed be protective — or harmful.

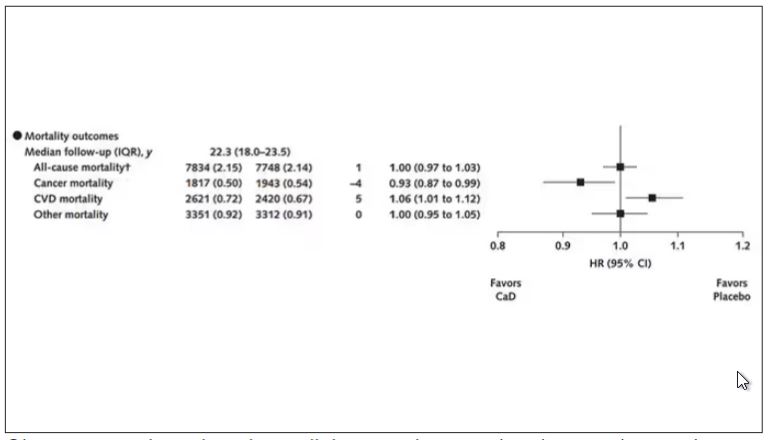

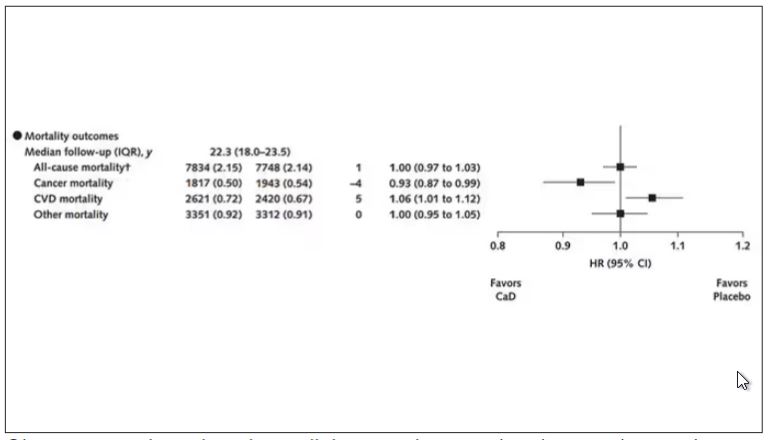

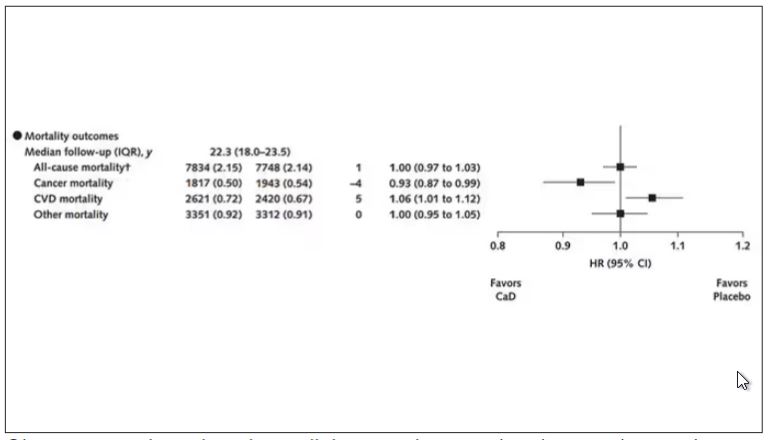

Here are the top-line results. Those randomized to vitamin D and calcium supplementation had a 7% reduction in the rate of death from cancer, driven primarily by a reduction in colorectal cancer. This was statistically significant. Also statistically significant? Those randomized to supplementation had a 6% increase in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease. Put those findings together and what do you get? Stone-cold nothing, in terms of overall mortality.

Okay, you say, but what about all that supplementation that was happening outside of the context of the trial, biasing our results toward the null?

The researchers finally clue us in.

First of all, I’ll tell you that, yes, people who were supplementing outside of the trial had higher baseline vitamin D levels — a median of 54.5 nmol/L vs 32.8 nmol/L. This may be because they were supplementing with vitamin D, but it could also be because people who take supplements tend to do other healthy things — another correlation to add to the great cathedral.

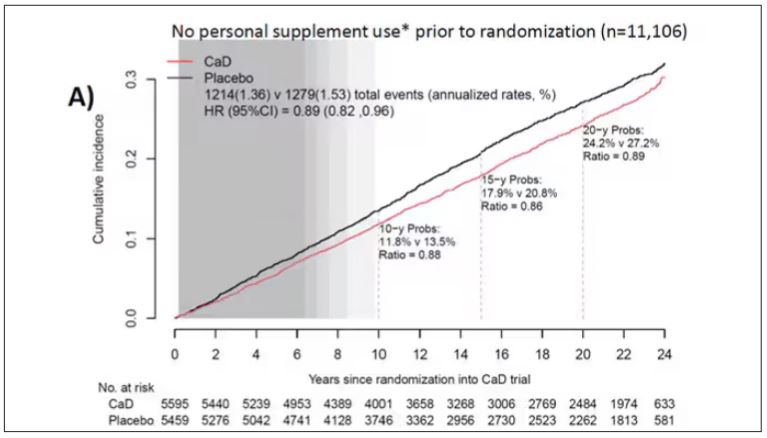

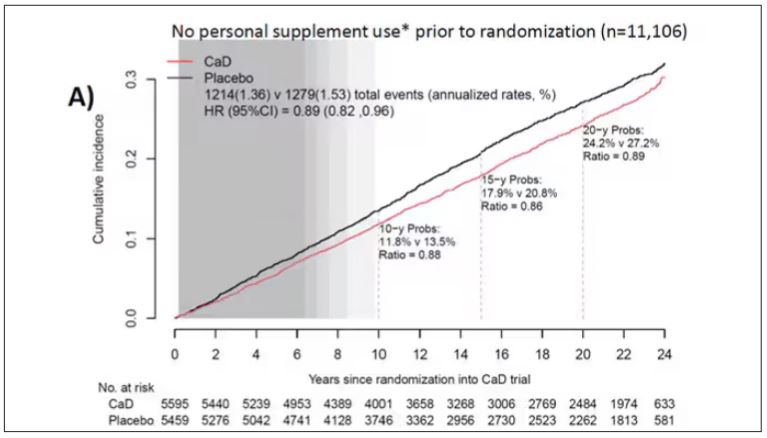

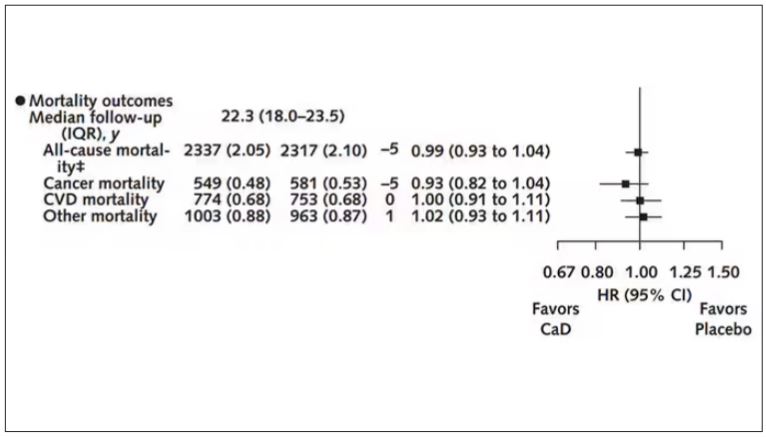

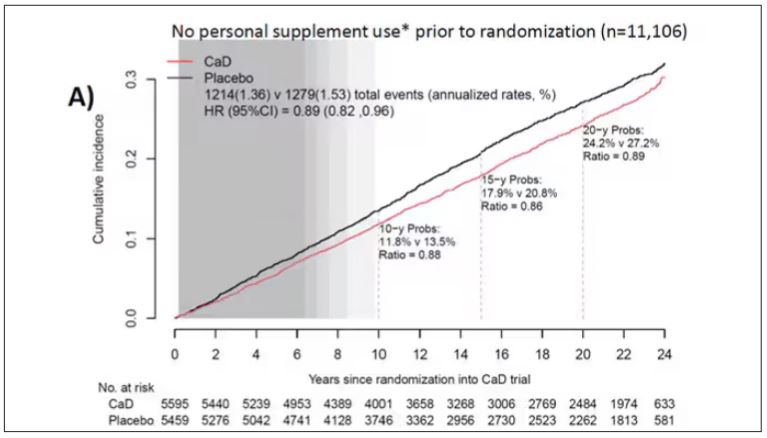

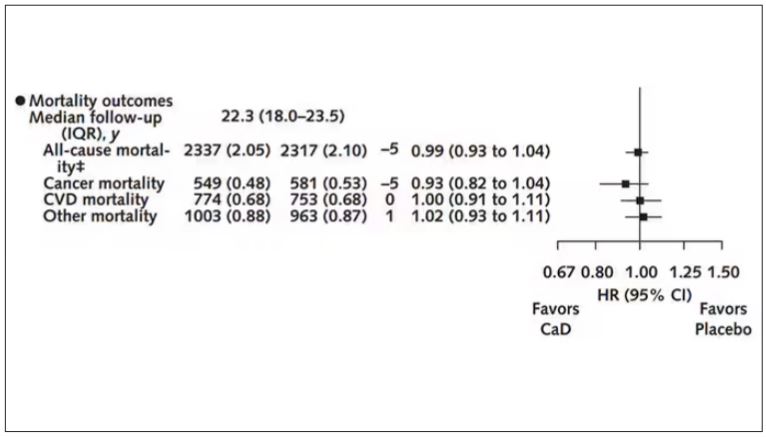

To get a better view of the real effects of randomization, the authors restricted the analysis to just those who did not use outside supplements. If vitamin D supplements help, then these are the people they should help. This group had about a 11% reduction in the incidence of cancer — statistically significant — and a 7% reduction in cancer mortality that did not meet the bar for statistical significance.

There was no increase in cardiovascular disease among this group. But this small effect on cancer was nowhere near enough to significantly reduce the rate of all-cause mortality.

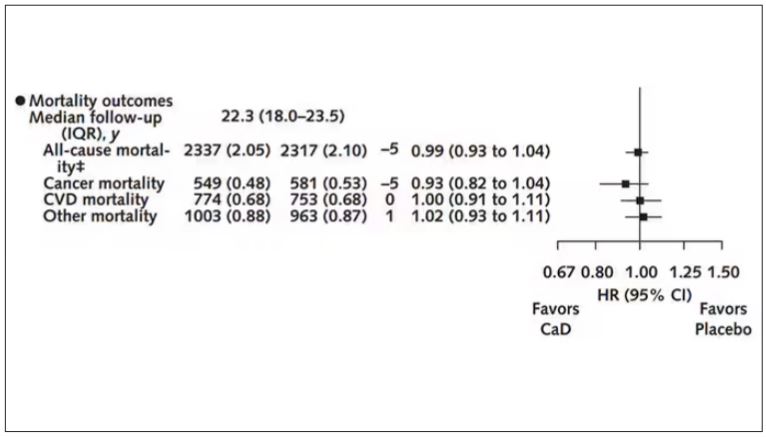

Among those using supplements, vitamin D supplementation didn’t really move the needle on any outcome.

I know what you’re thinking: How many of these women were vitamin D deficient when we got started? These results may simply be telling us that people who have normal vitamin D levels are fine to go without supplementation.

Nearly three fourths of women who were not taking supplements entered the trial with vitamin D levels below the 50 nmol/L cutoff that the authors suggest would qualify for deficiency. Around half of those who used supplements were deficient. And yet, frustratingly, I could not find data on the effect of randomization to supplementation stratified by baseline vitamin D level. I even reached out to Dr Thomson to ask about this. She replied, “We did not stratify on baseline values because the numbers are too small statistically to test this.” Sorry.

In the meantime, I can tell you that for your “average woman,” vitamin D supplementation likely has no effect on mortality. It might modestly reduce the risk for certain cancers while increasing the risk for heart disease (probably through coronary calcification). So, there might be some room for personalization here. Perhaps women with a strong family history of cancer or other risk factors would do better with supplements, and those with a high risk for heart disease would do worse. Seems like a strategy that could be tested in a clinical trial. But maybe we could ask the participants to give up their extracurricular supplement use before they enter the trial. F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.

The randomized trial itself only lasted 7 years. What we are seeing in this analysis of 36,282 women is outcomes that happened at any time from randomization to the end of 2023 — around 20 years after the randomization to supplementation stopped. But, the researchers would argue, that’s probably okay. Cancer and heart disease take time to develop; we see lung cancer long after people stop smoking. So a history of consistent vitamin D supplementation may indeed be protective — or harmful.

Here are the top-line results. Those randomized to vitamin D and calcium supplementation had a 7% reduction in the rate of death from cancer, driven primarily by a reduction in colorectal cancer. This was statistically significant. Also statistically significant? Those randomized to supplementation had a 6% increase in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease. Put those findings together and what do you get? Stone-cold nothing, in terms of overall mortality.

Okay, you say, but what about all that supplementation that was happening outside of the context of the trial, biasing our results toward the null?

The researchers finally clue us in.

First of all, I’ll tell you that, yes, people who were supplementing outside of the trial had higher baseline vitamin D levels — a median of 54.5 nmol/L vs 32.8 nmol/L. This may be because they were supplementing with vitamin D, but it could also be because people who take supplements tend to do other healthy things — another correlation to add to the great cathedral.

To get a better view of the real effects of randomization, the authors restricted the analysis to just those who did not use outside supplements. If vitamin D supplements help, then these are the people they should help. This group had about a 11% reduction in the incidence of cancer — statistically significant — and a 7% reduction in cancer mortality that did not meet the bar for statistical significance.

There was no increase in cardiovascular disease among this group. But this small effect on cancer was nowhere near enough to significantly reduce the rate of all-cause mortality.

Among those using supplements, vitamin D supplementation didn’t really move the needle on any outcome.

I know what you’re thinking: How many of these women were vitamin D deficient when we got started? These results may simply be telling us that people who have normal vitamin D levels are fine to go without supplementation.

Nearly three fourths of women who were not taking supplements entered the trial with vitamin D levels below the 50 nmol/L cutoff that the authors suggest would qualify for deficiency. Around half of those who used supplements were deficient. And yet, frustratingly, I could not find data on the effect of randomization to supplementation stratified by baseline vitamin D level. I even reached out to Dr Thomson to ask about this. She replied, “We did not stratify on baseline values because the numbers are too small statistically to test this.” Sorry.

In the meantime, I can tell you that for your “average woman,” vitamin D supplementation likely has no effect on mortality. It might modestly reduce the risk for certain cancers while increasing the risk for heart disease (probably through coronary calcification). So, there might be some room for personalization here. Perhaps women with a strong family history of cancer or other risk factors would do better with supplements, and those with a high risk for heart disease would do worse. Seems like a strategy that could be tested in a clinical trial. But maybe we could ask the participants to give up their extracurricular supplement use before they enter the trial. F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.

The randomized trial itself only lasted 7 years. What we are seeing in this analysis of 36,282 women is outcomes that happened at any time from randomization to the end of 2023 — around 20 years after the randomization to supplementation stopped. But, the researchers would argue, that’s probably okay. Cancer and heart disease take time to develop; we see lung cancer long after people stop smoking. So a history of consistent vitamin D supplementation may indeed be protective — or harmful.

Here are the top-line results. Those randomized to vitamin D and calcium supplementation had a 7% reduction in the rate of death from cancer, driven primarily by a reduction in colorectal cancer. This was statistically significant. Also statistically significant? Those randomized to supplementation had a 6% increase in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease. Put those findings together and what do you get? Stone-cold nothing, in terms of overall mortality.

Okay, you say, but what about all that supplementation that was happening outside of the context of the trial, biasing our results toward the null?

The researchers finally clue us in.

First of all, I’ll tell you that, yes, people who were supplementing outside of the trial had higher baseline vitamin D levels — a median of 54.5 nmol/L vs 32.8 nmol/L. This may be because they were supplementing with vitamin D, but it could also be because people who take supplements tend to do other healthy things — another correlation to add to the great cathedral.

To get a better view of the real effects of randomization, the authors restricted the analysis to just those who did not use outside supplements. If vitamin D supplements help, then these are the people they should help. This group had about a 11% reduction in the incidence of cancer — statistically significant — and a 7% reduction in cancer mortality that did not meet the bar for statistical significance.

There was no increase in cardiovascular disease among this group. But this small effect on cancer was nowhere near enough to significantly reduce the rate of all-cause mortality.

Among those using supplements, vitamin D supplementation didn’t really move the needle on any outcome.

I know what you’re thinking: How many of these women were vitamin D deficient when we got started? These results may simply be telling us that people who have normal vitamin D levels are fine to go without supplementation.

Nearly three fourths of women who were not taking supplements entered the trial with vitamin D levels below the 50 nmol/L cutoff that the authors suggest would qualify for deficiency. Around half of those who used supplements were deficient. And yet, frustratingly, I could not find data on the effect of randomization to supplementation stratified by baseline vitamin D level. I even reached out to Dr Thomson to ask about this. She replied, “We did not stratify on baseline values because the numbers are too small statistically to test this.” Sorry.

In the meantime, I can tell you that for your “average woman,” vitamin D supplementation likely has no effect on mortality. It might modestly reduce the risk for certain cancers while increasing the risk for heart disease (probably through coronary calcification). So, there might be some room for personalization here. Perhaps women with a strong family history of cancer or other risk factors would do better with supplements, and those with a high risk for heart disease would do worse. Seems like a strategy that could be tested in a clinical trial. But maybe we could ask the participants to give up their extracurricular supplement use before they enter the trial. F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

COVID-19 Is a Very Weird Virus

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

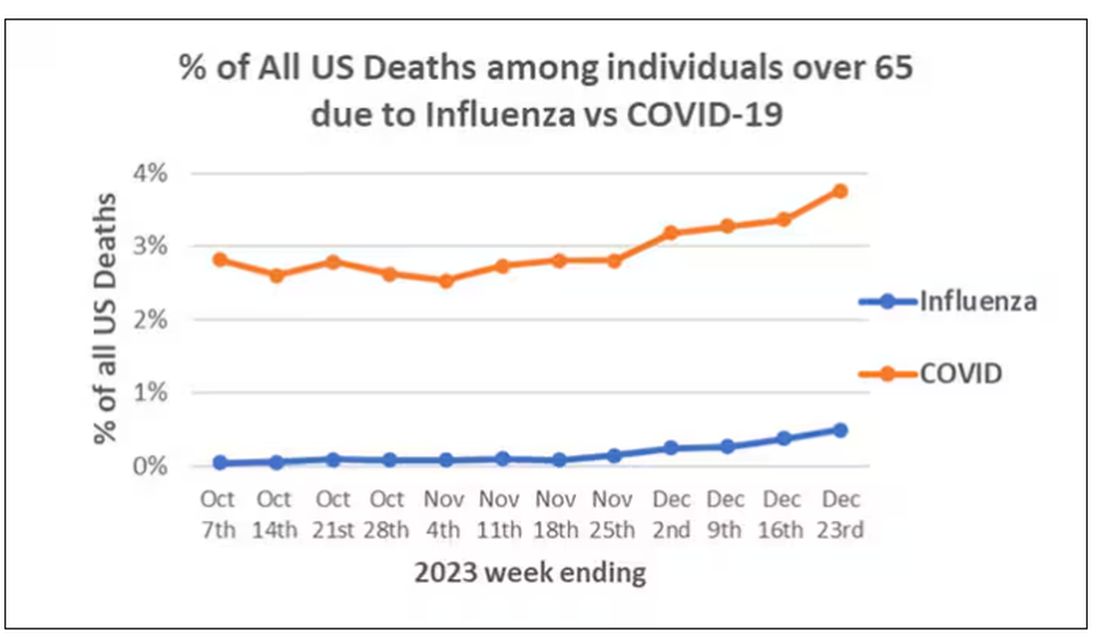

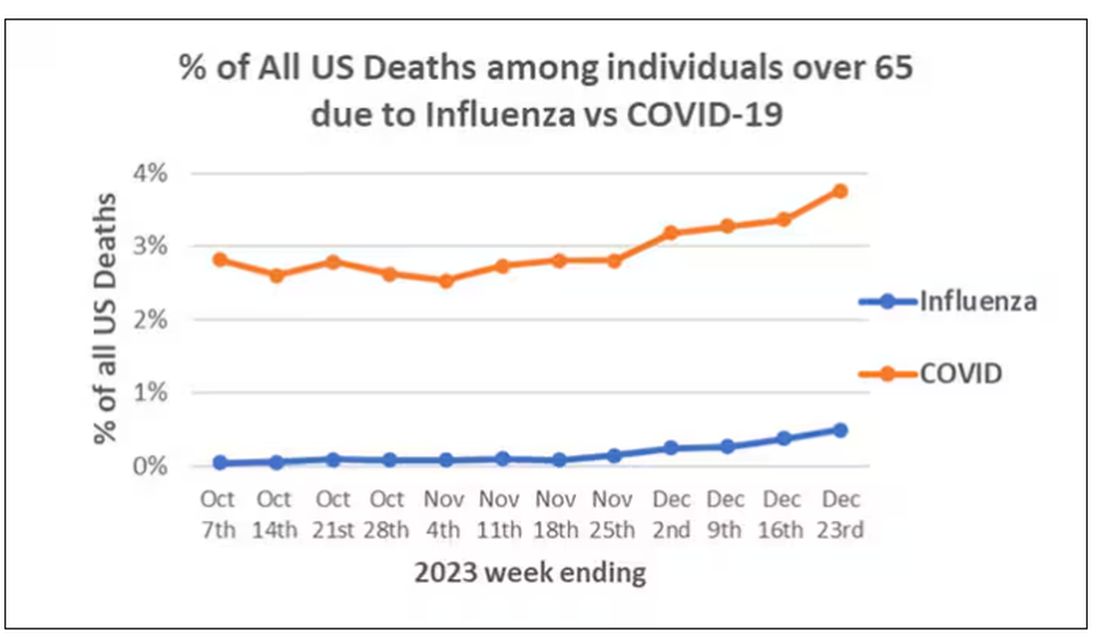

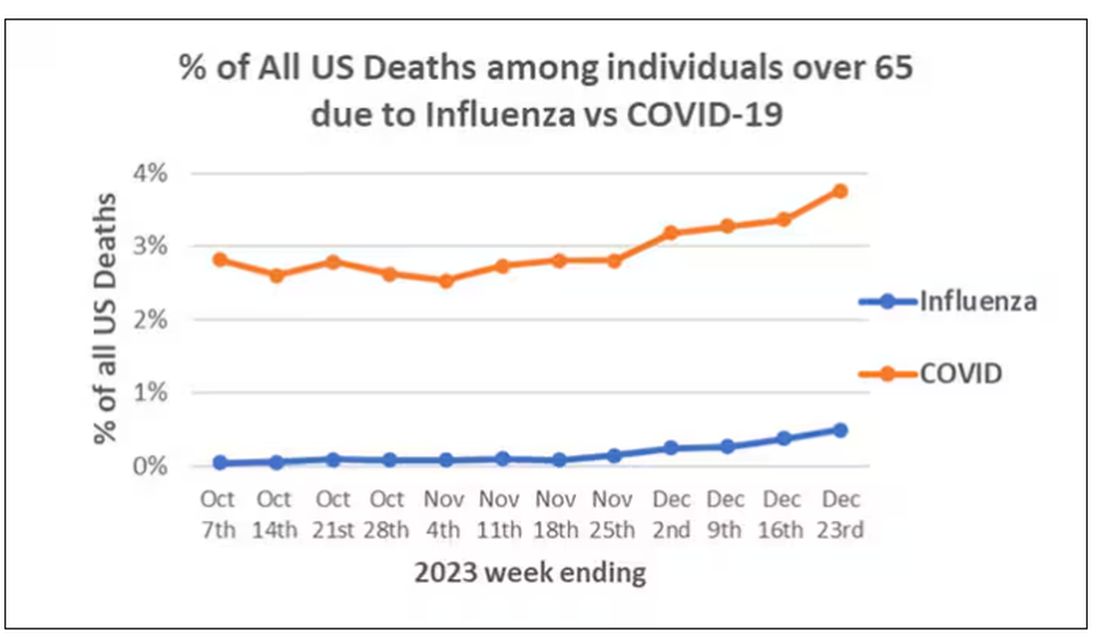

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

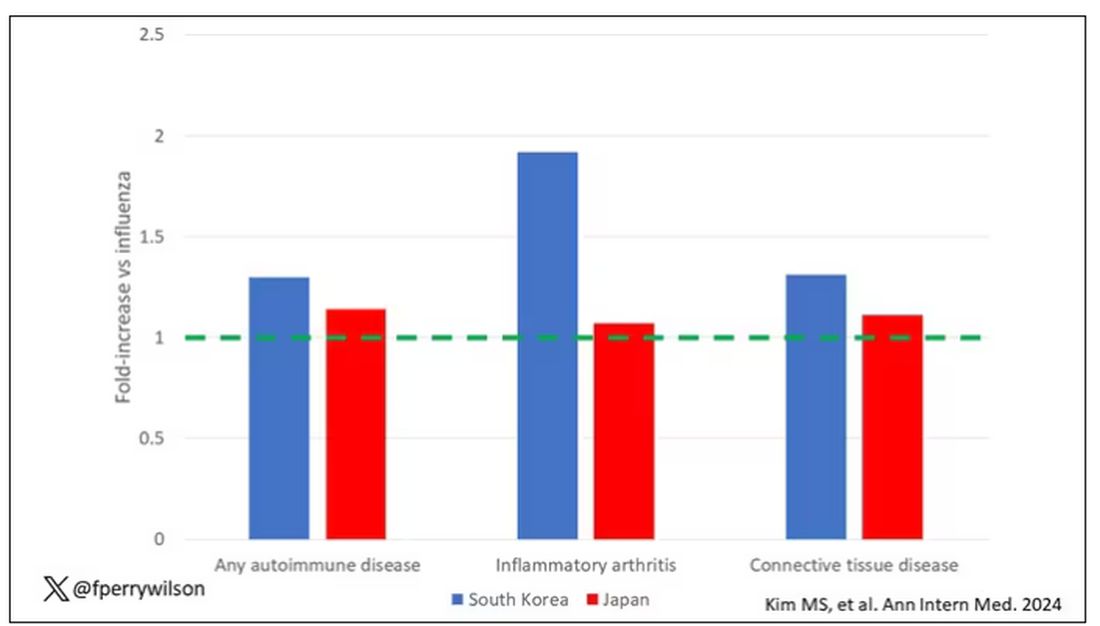

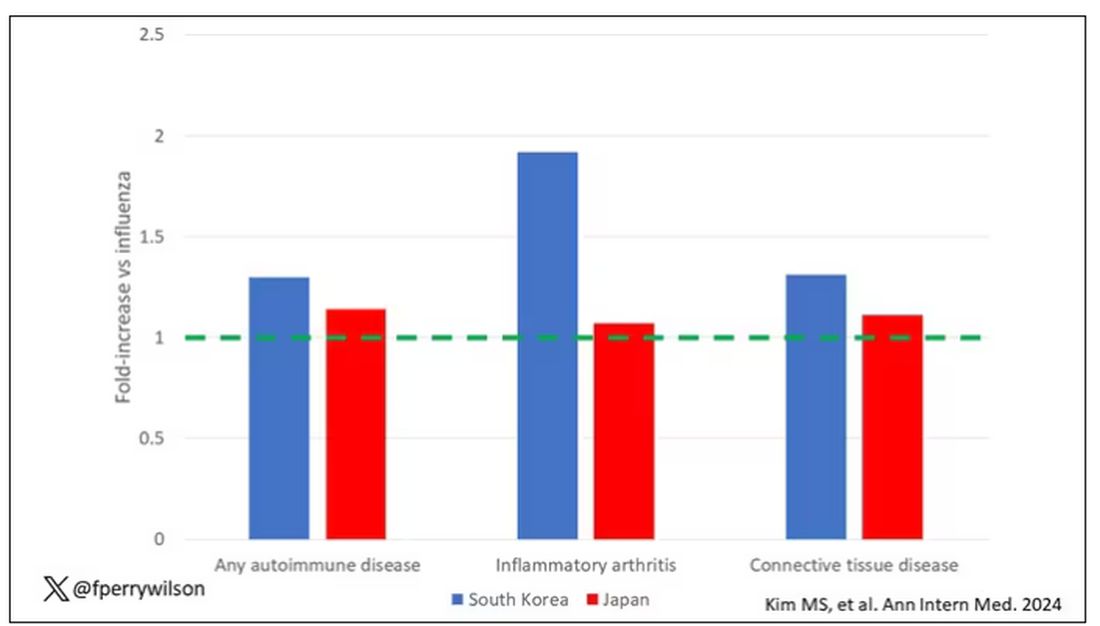

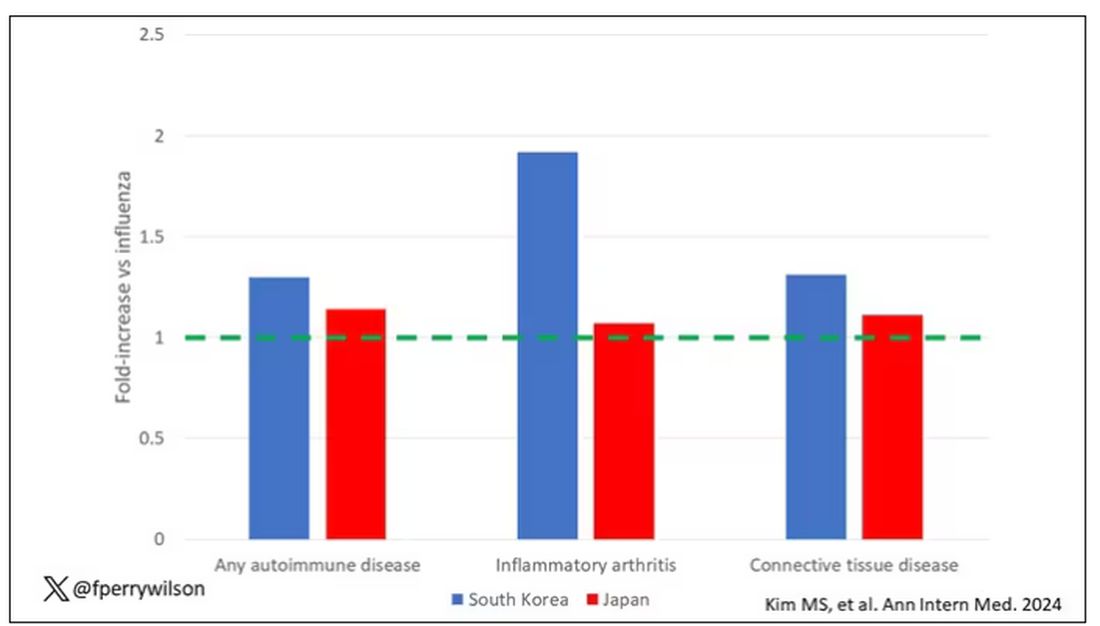

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

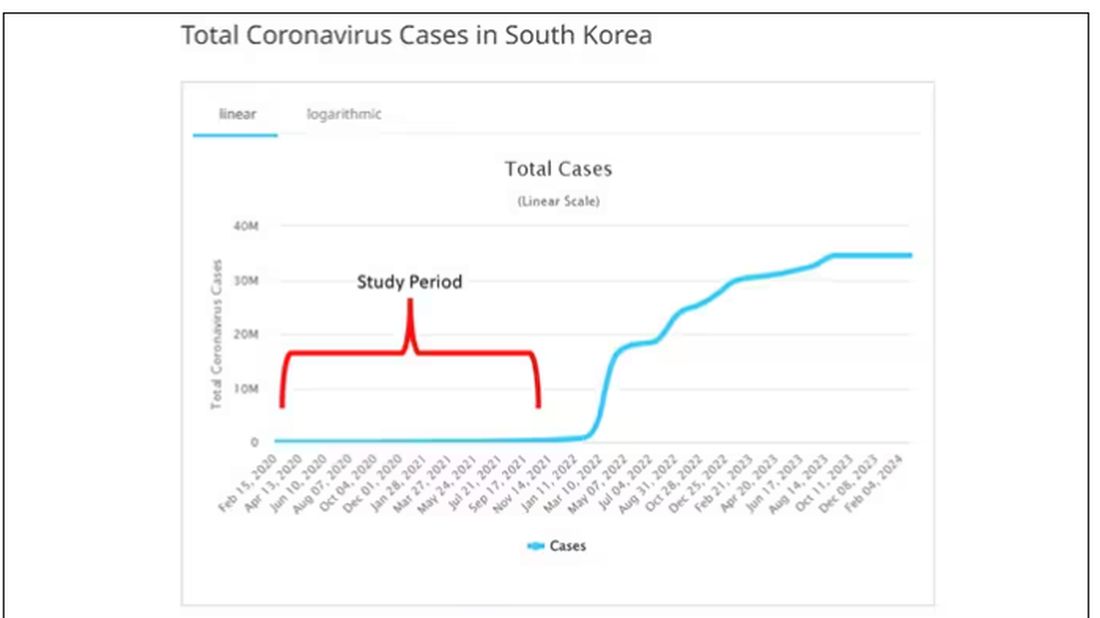

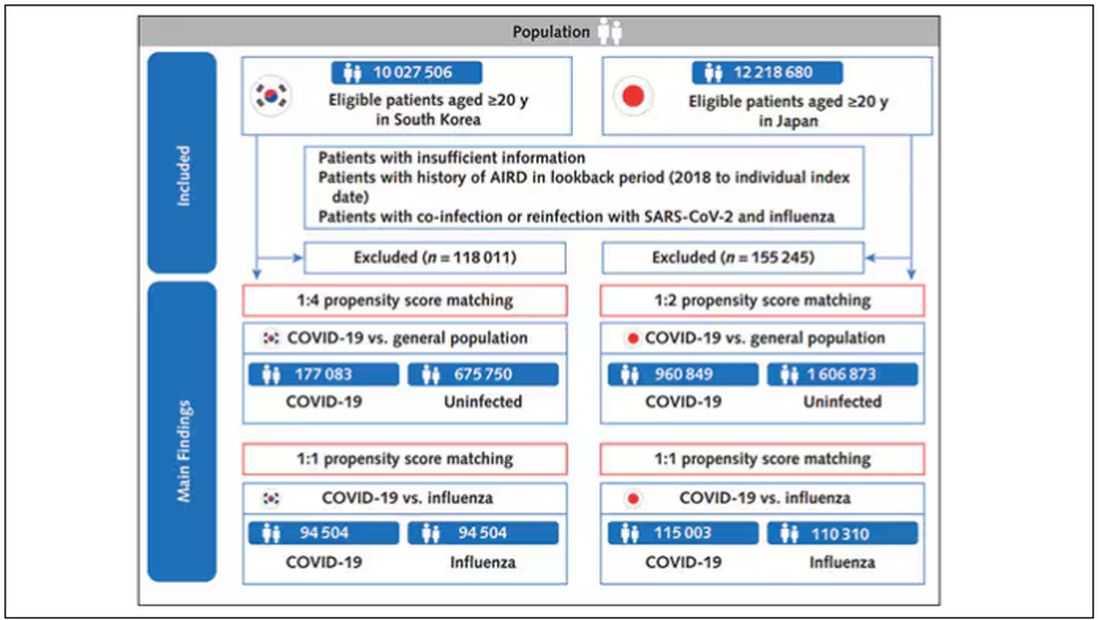

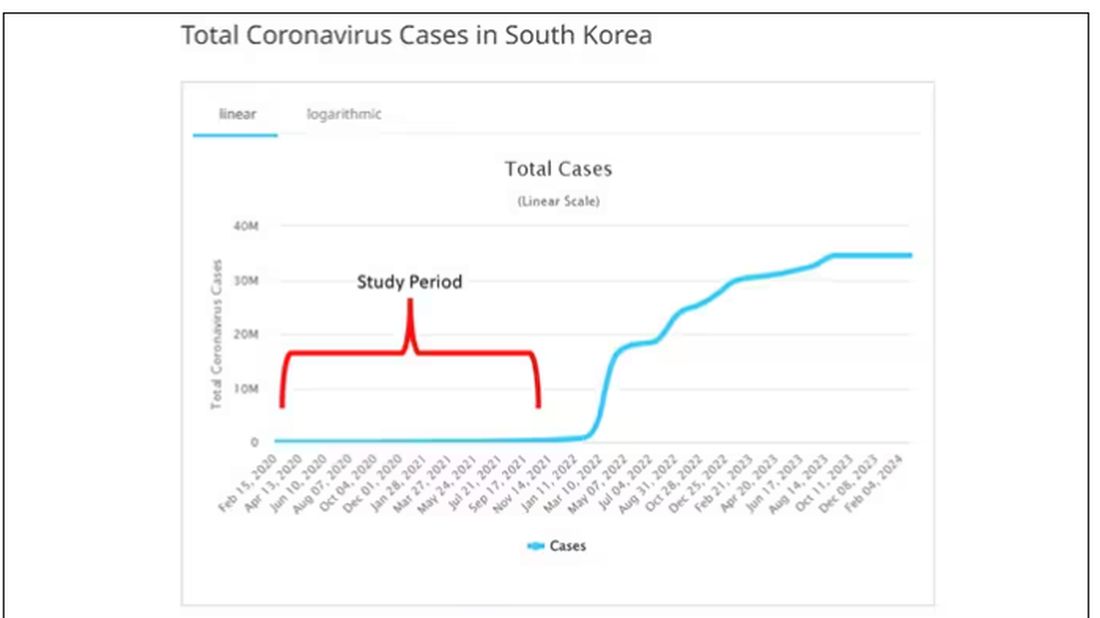

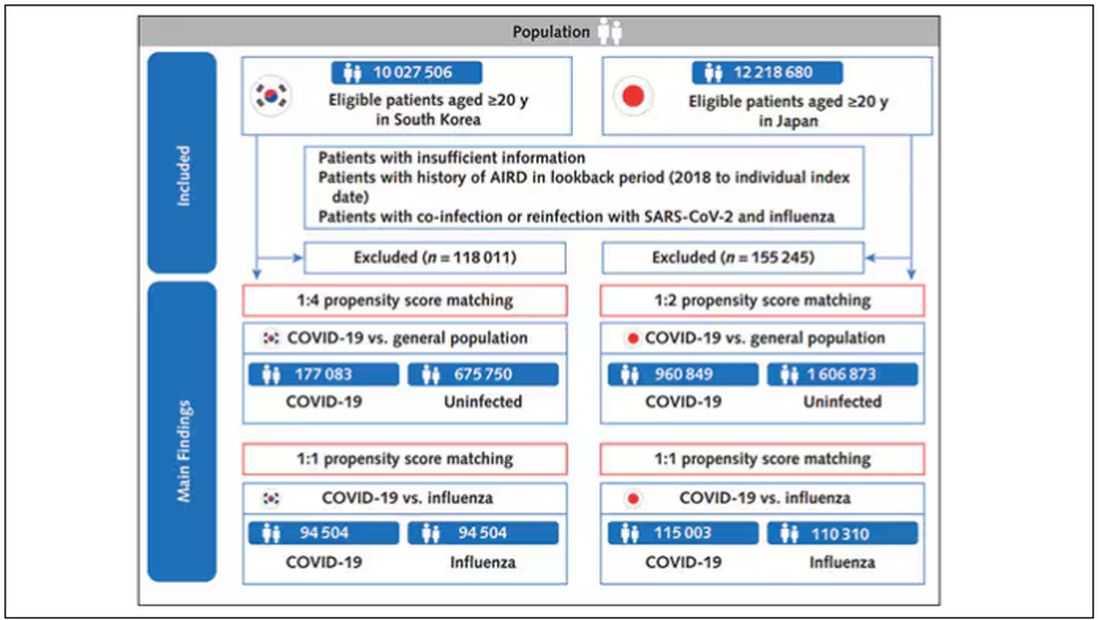

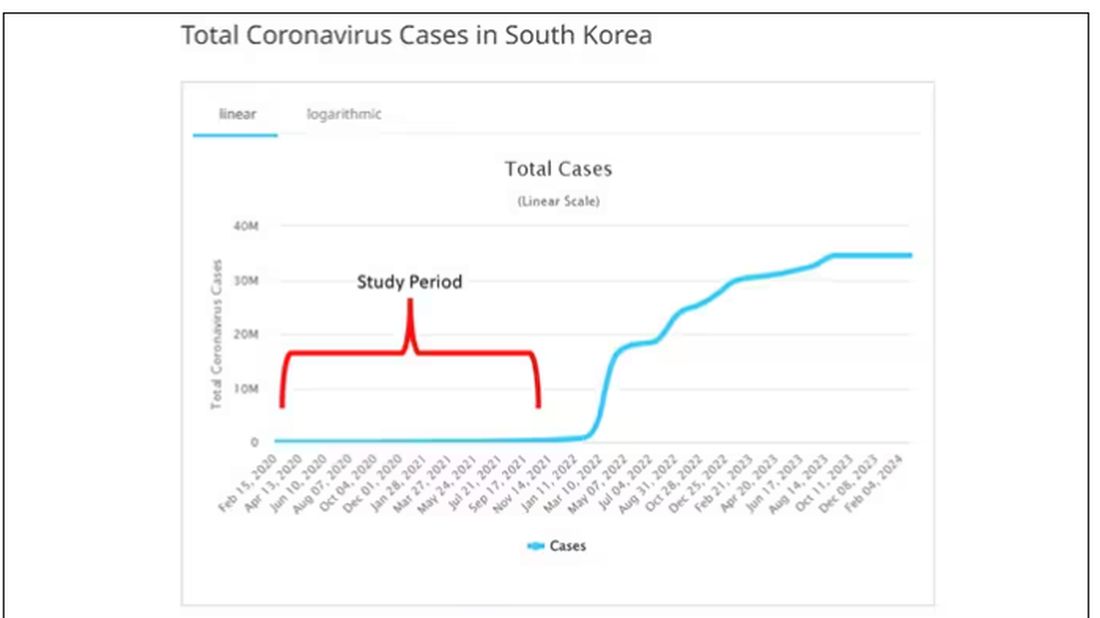

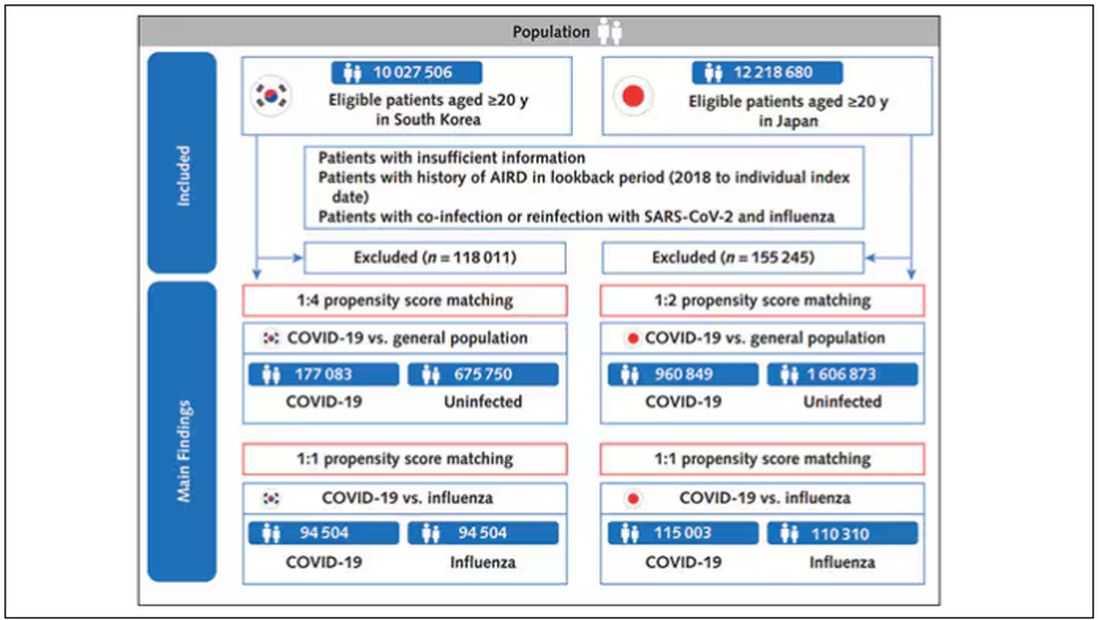

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

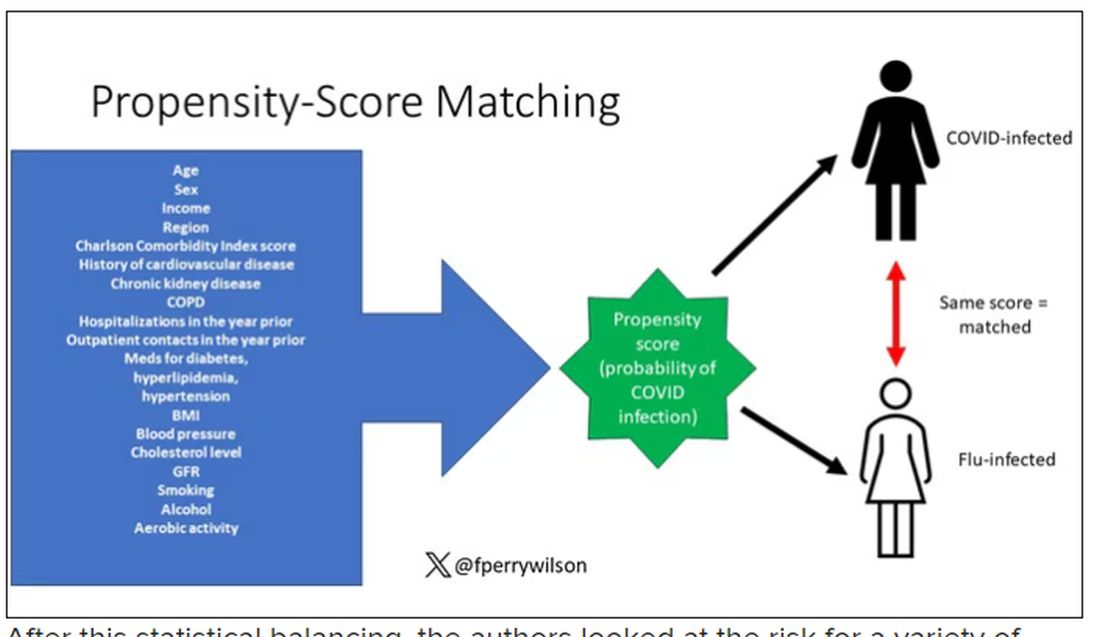

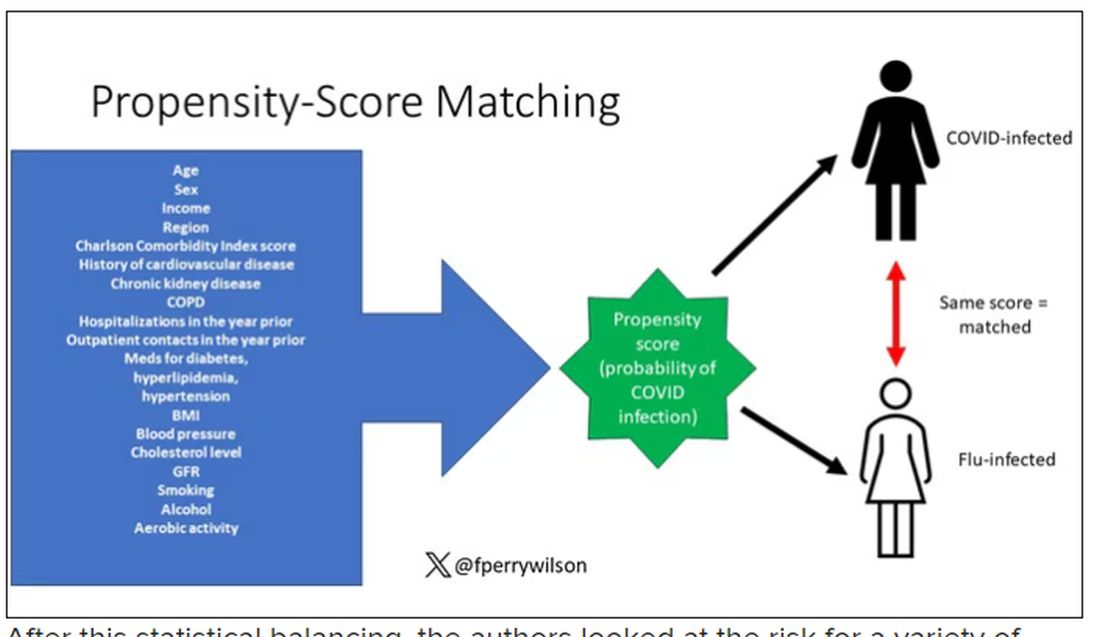

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

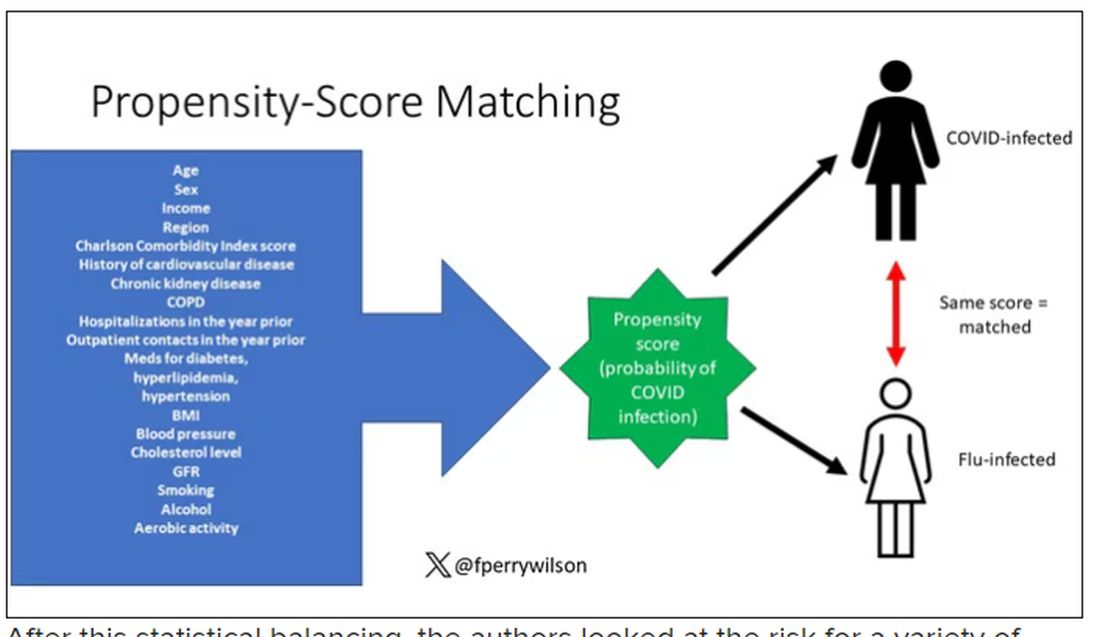

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

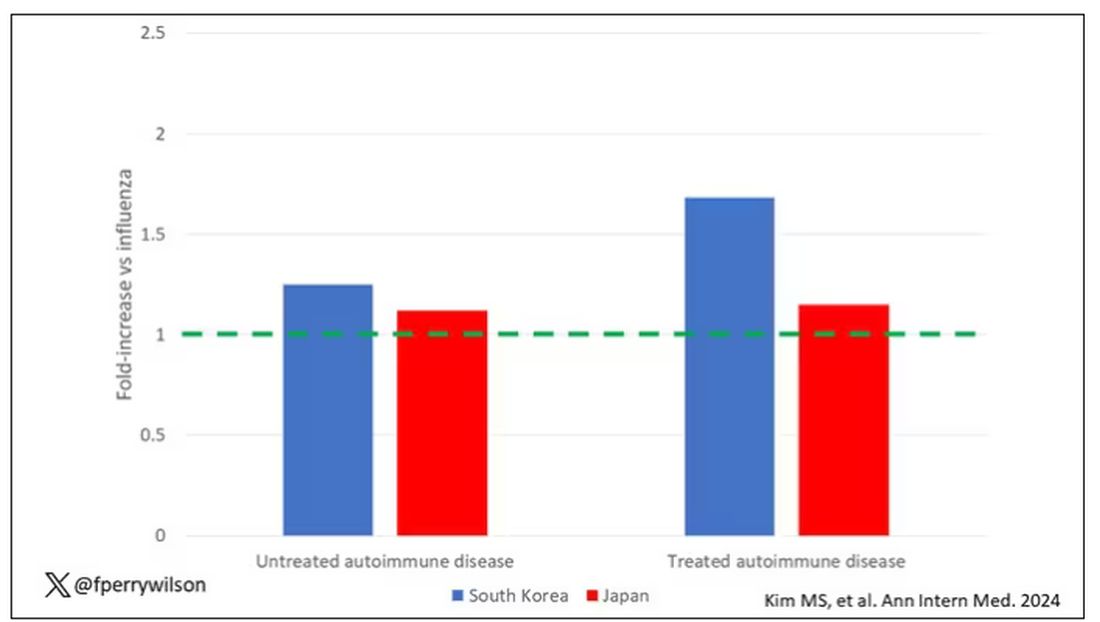

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

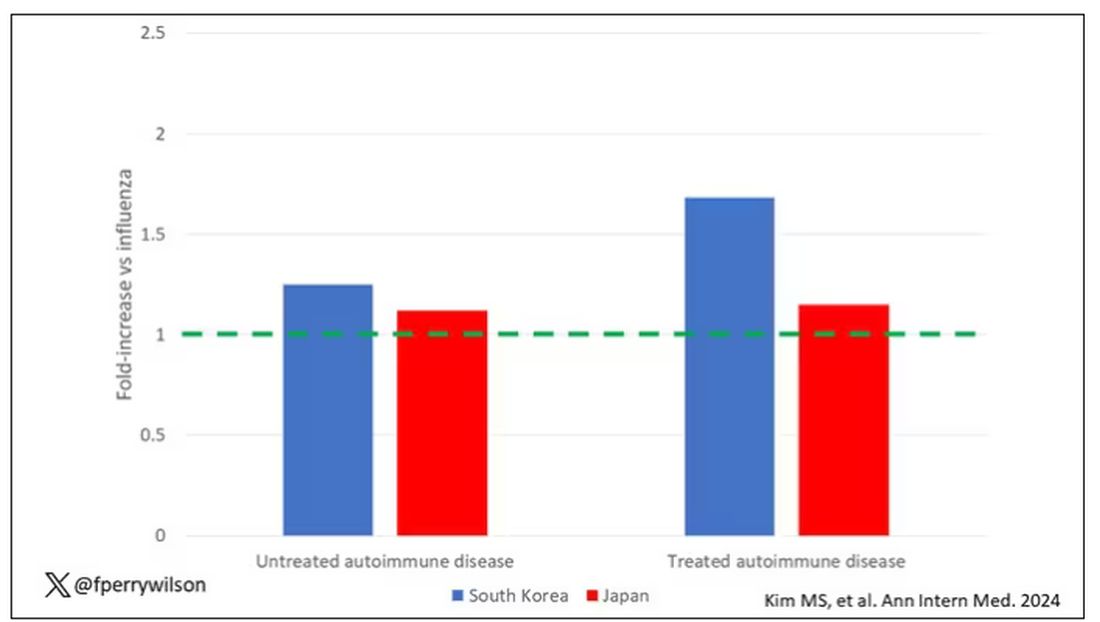

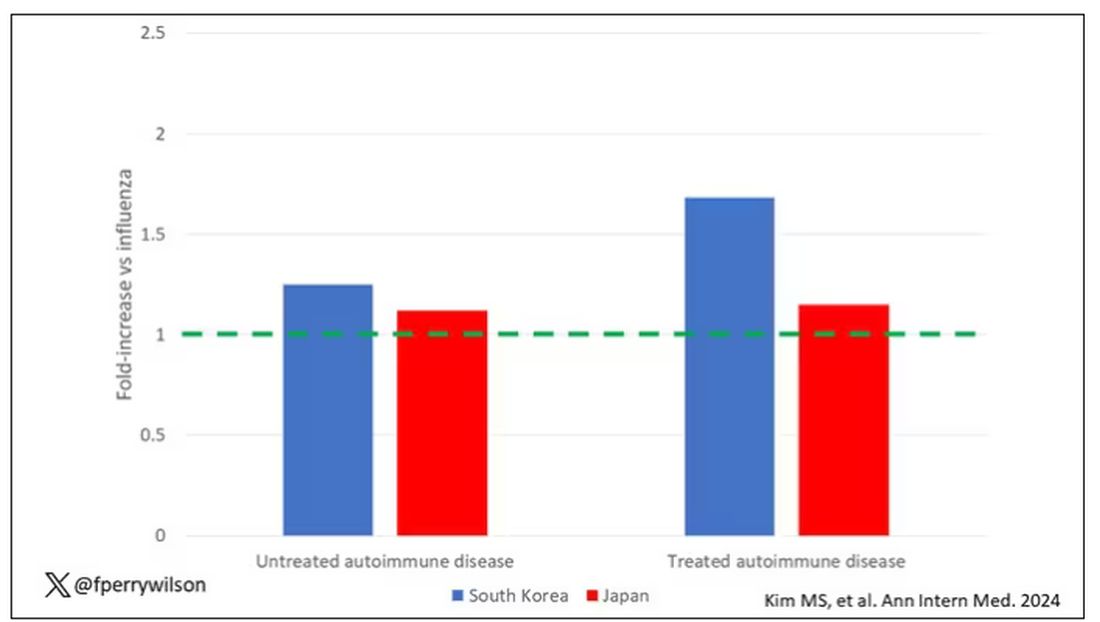

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

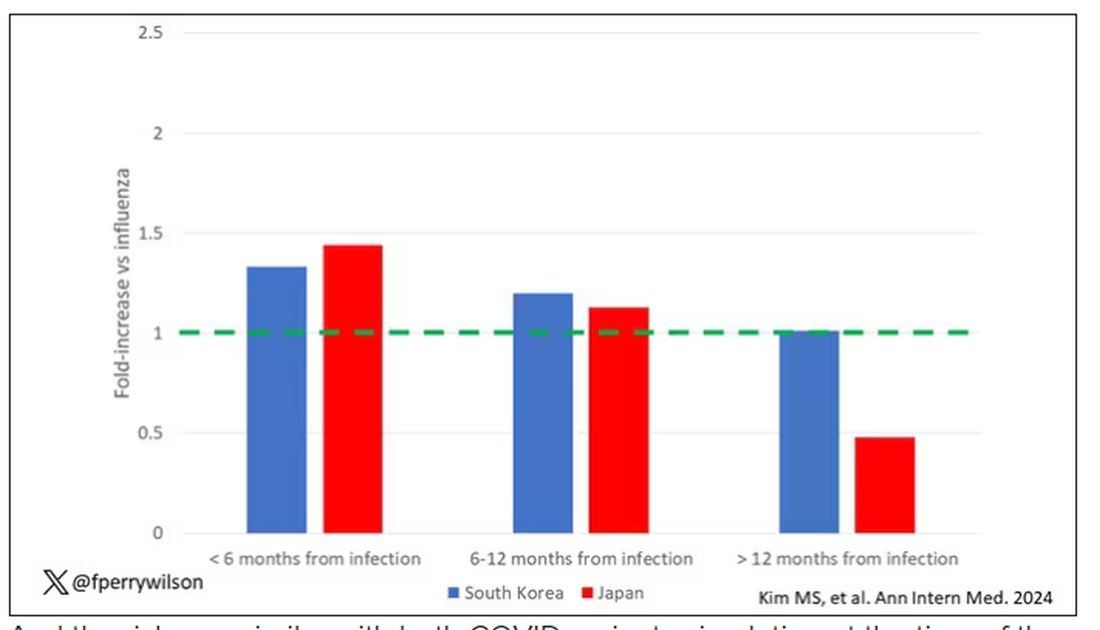

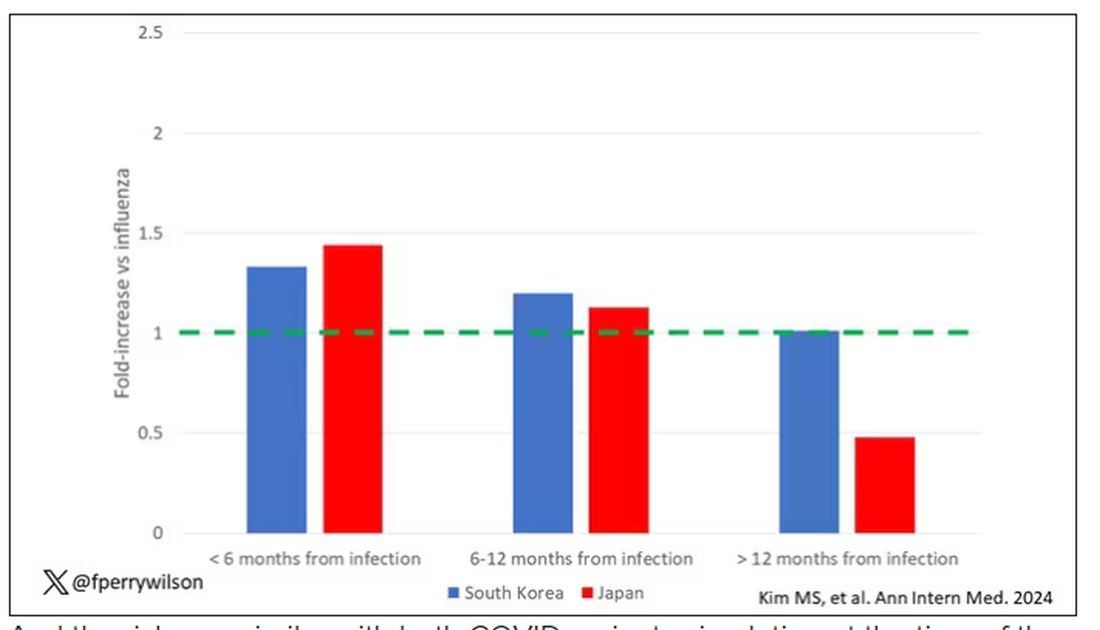

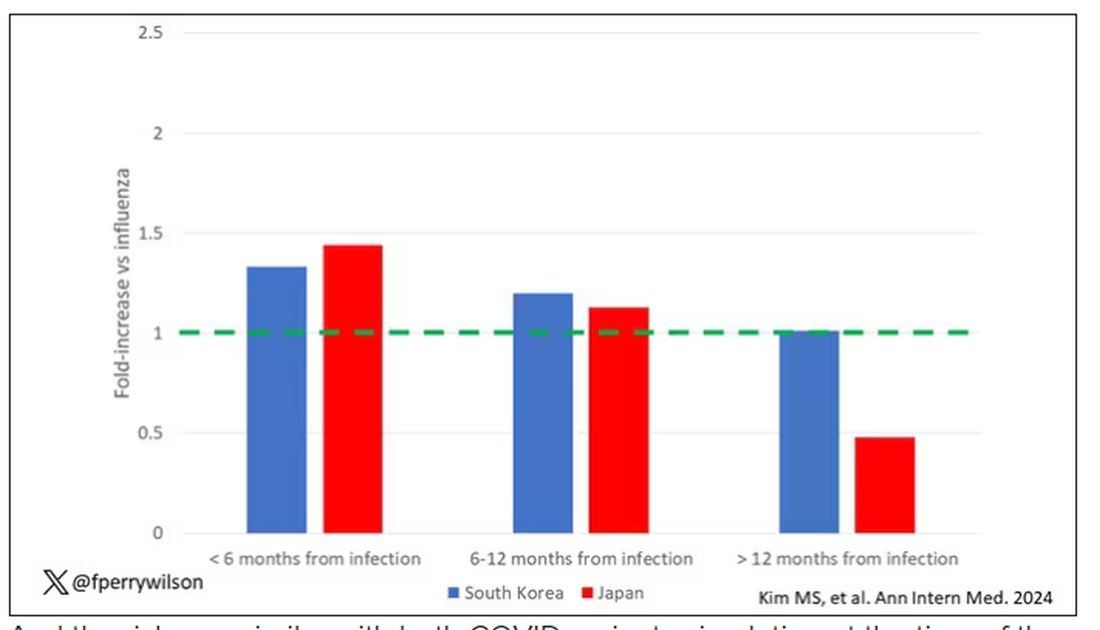

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

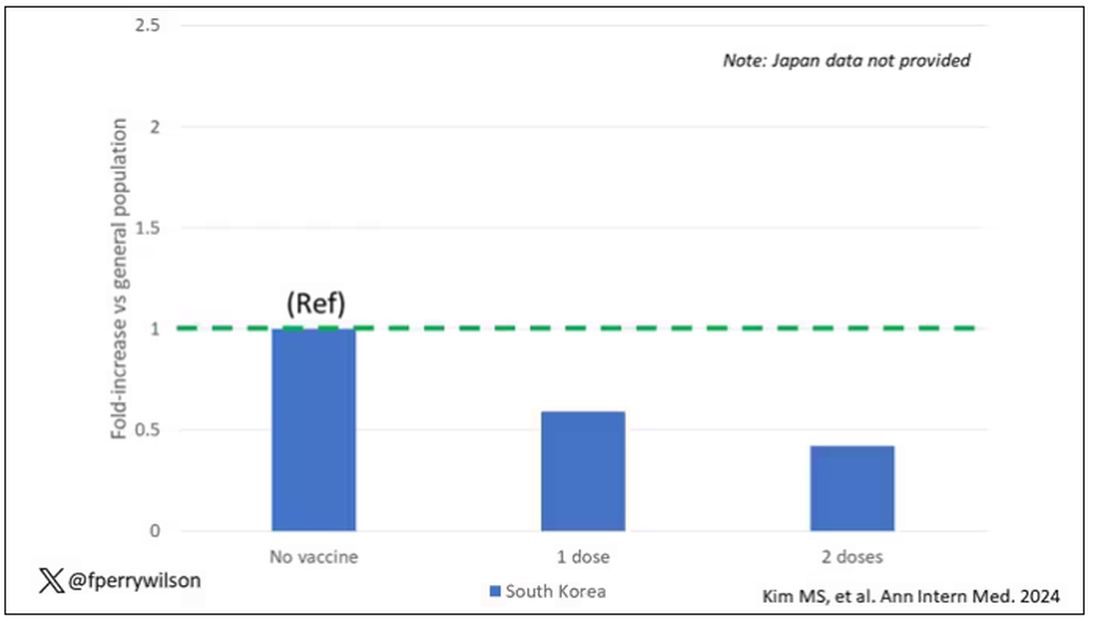

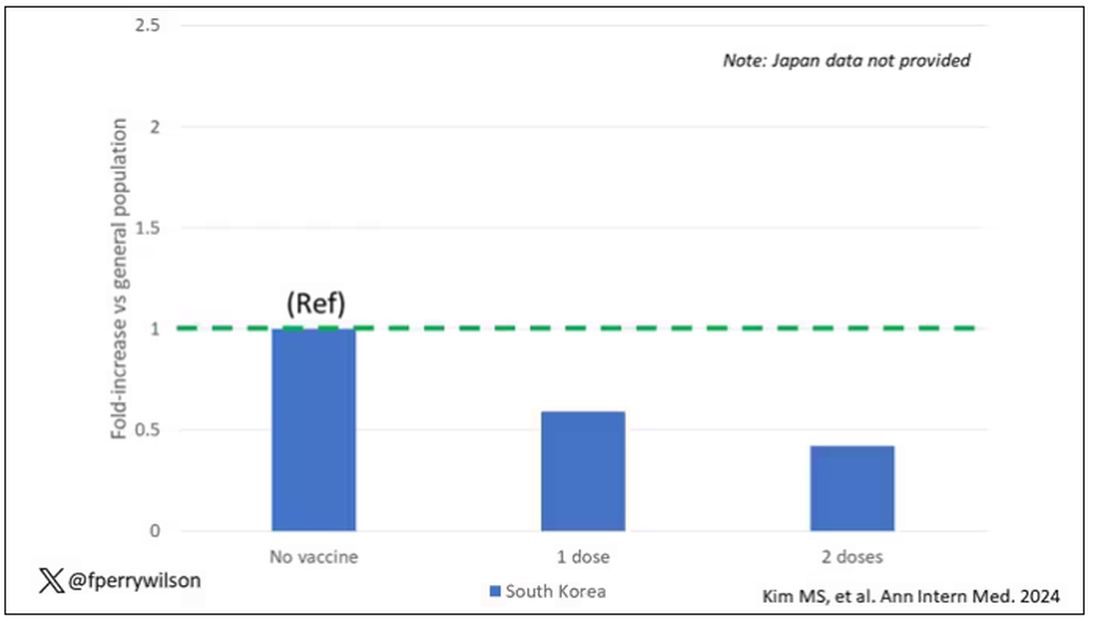

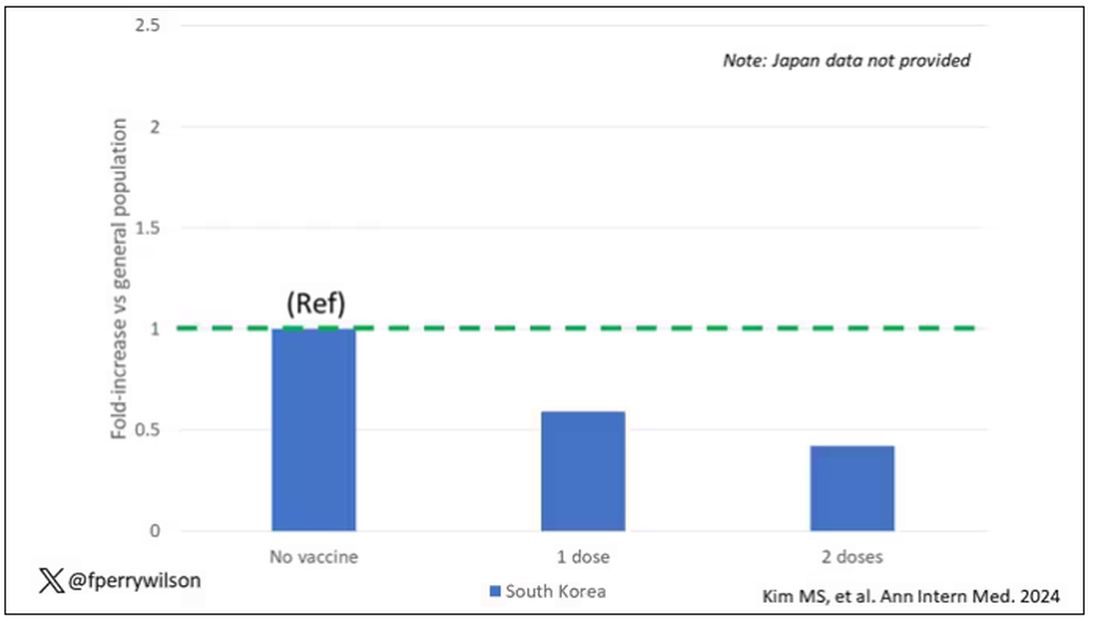

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

It Sure Looks Like Cannabis Is Bad for the Heart, Doesn’t It?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

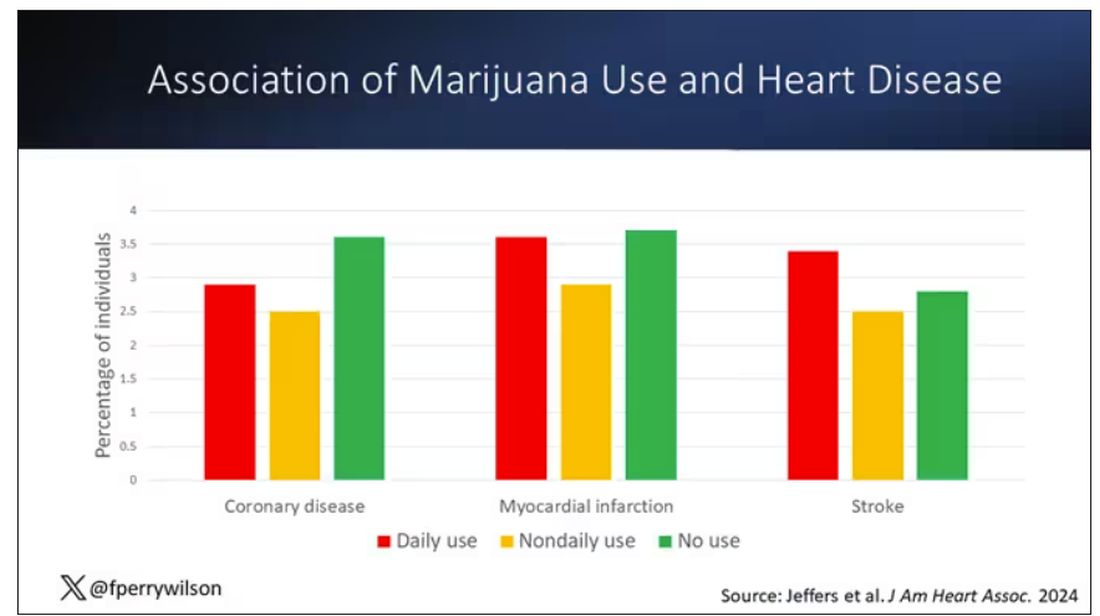

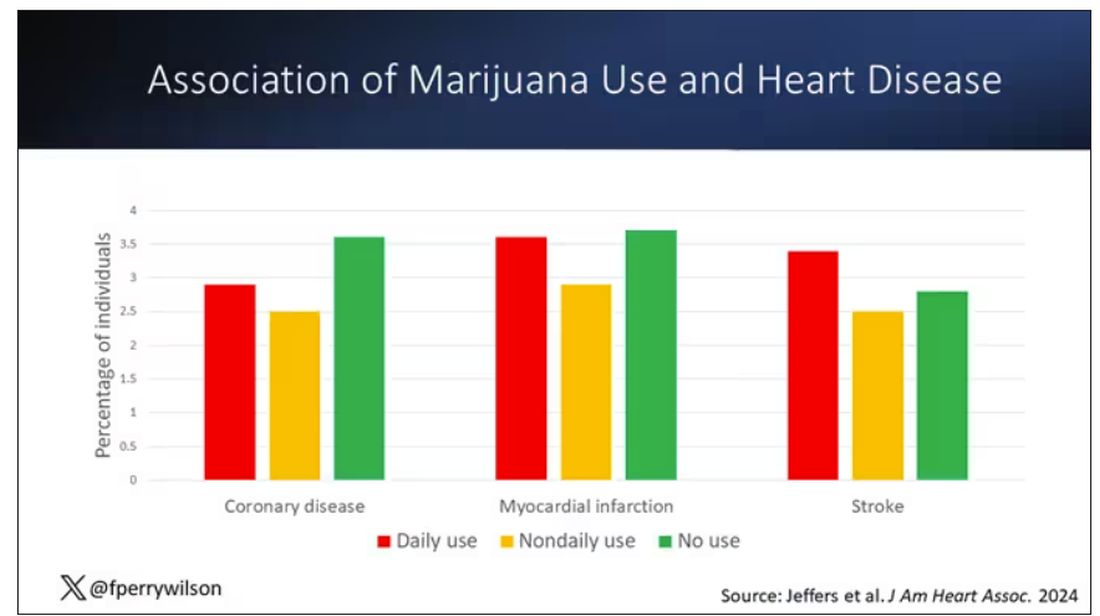

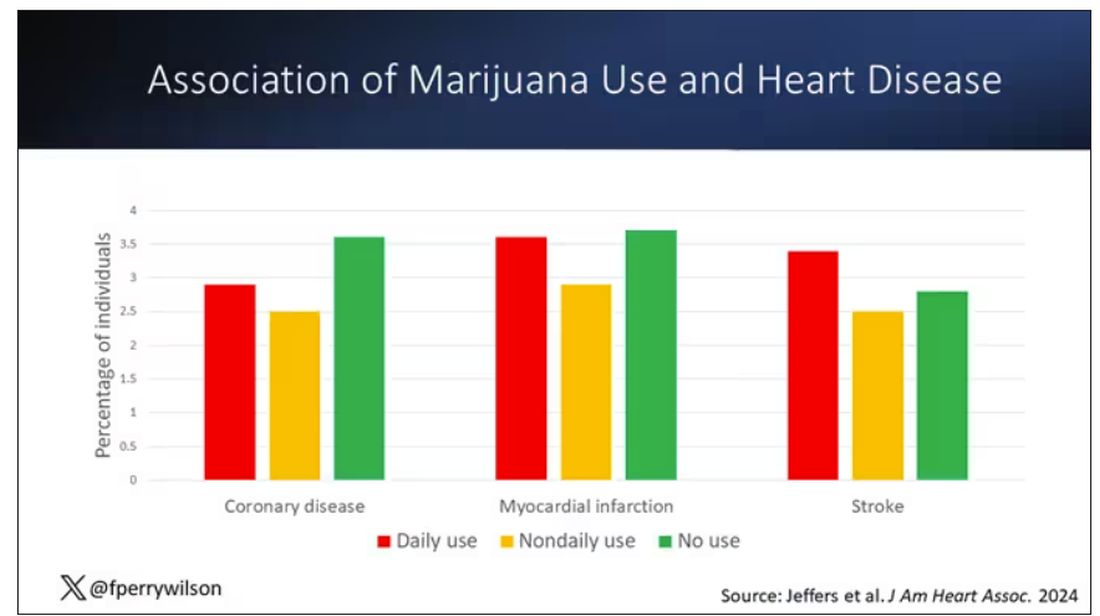

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

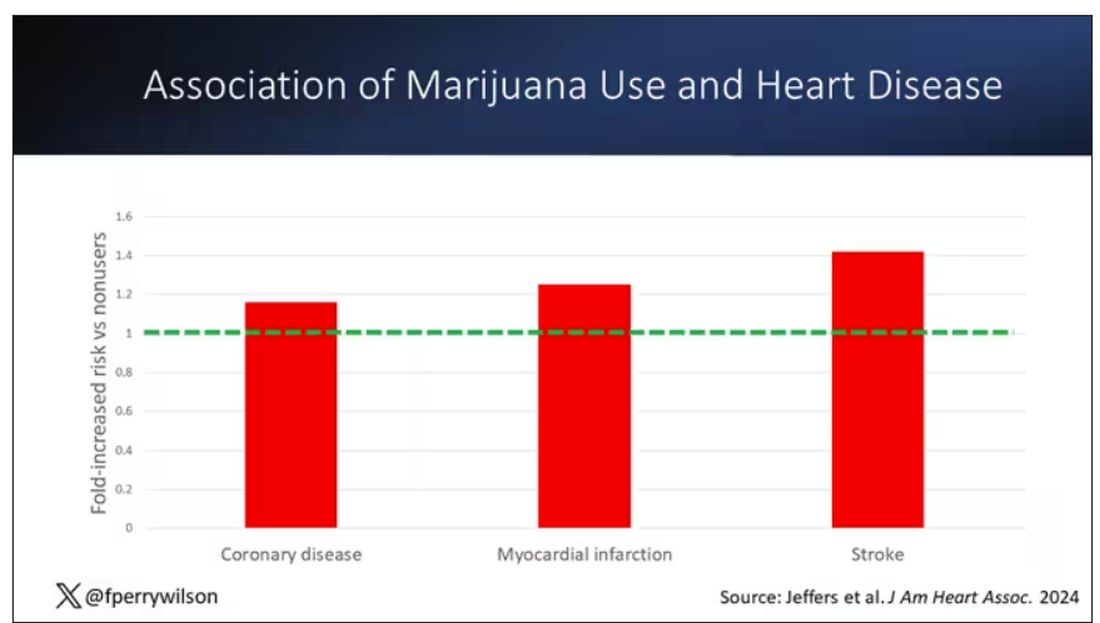

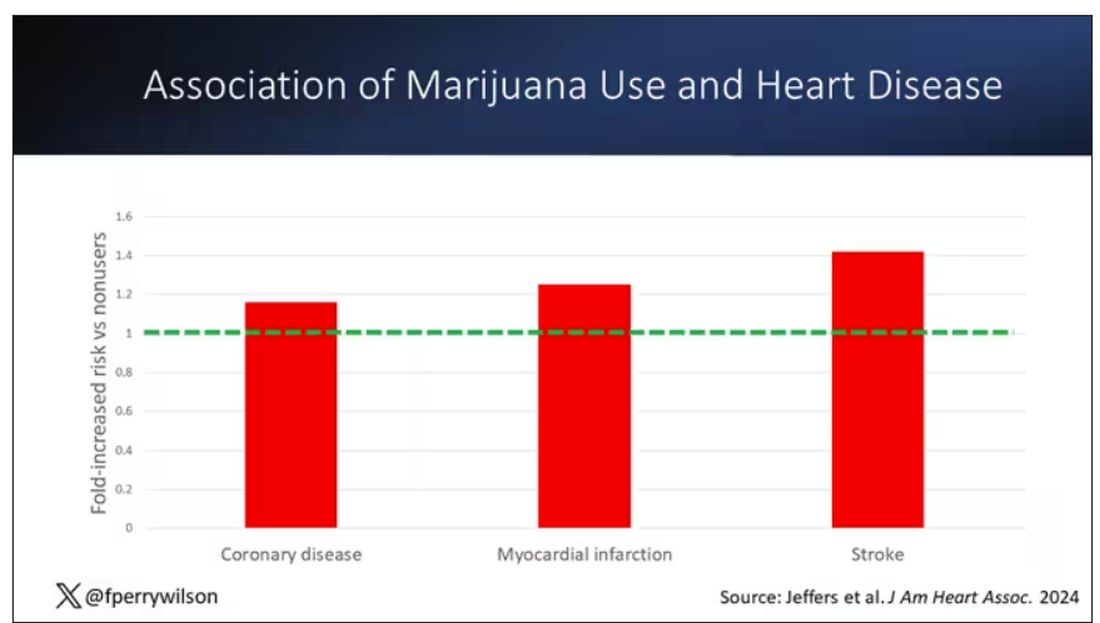

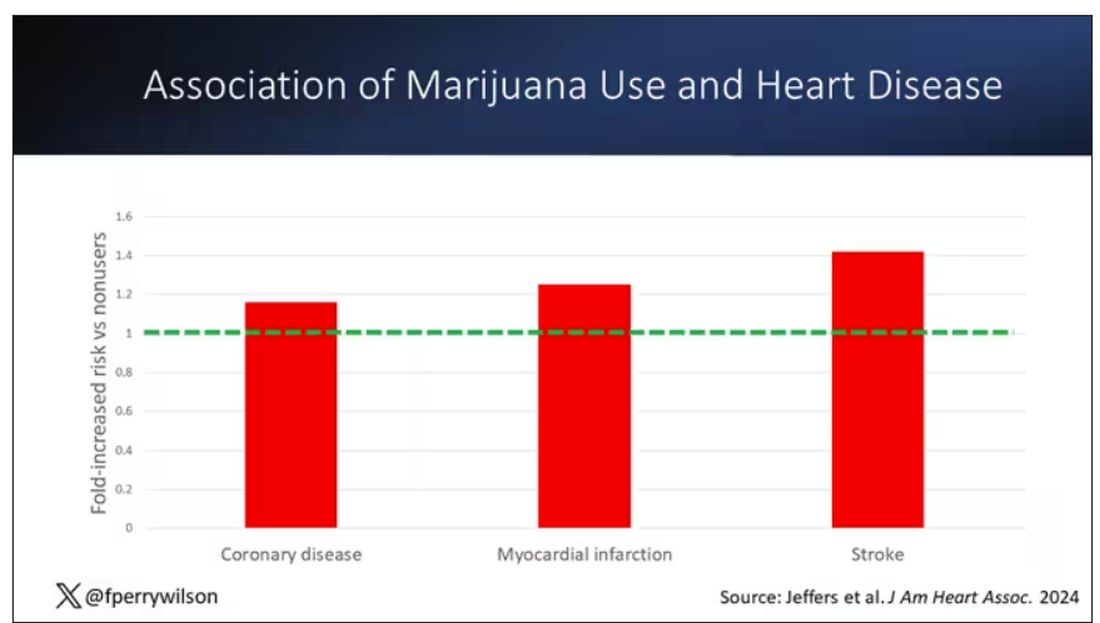

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

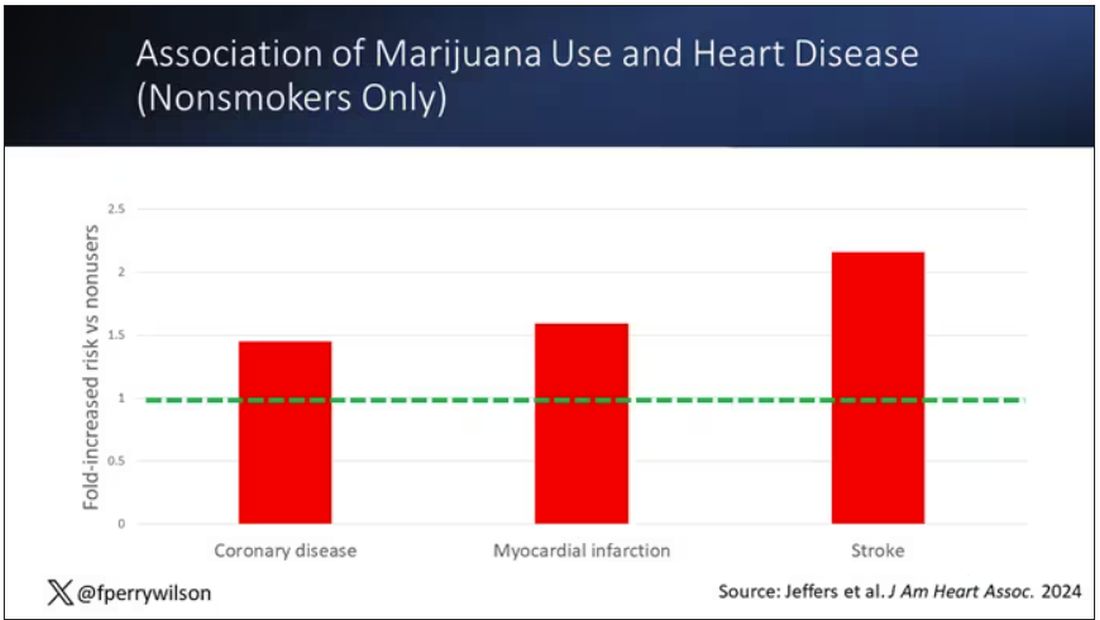

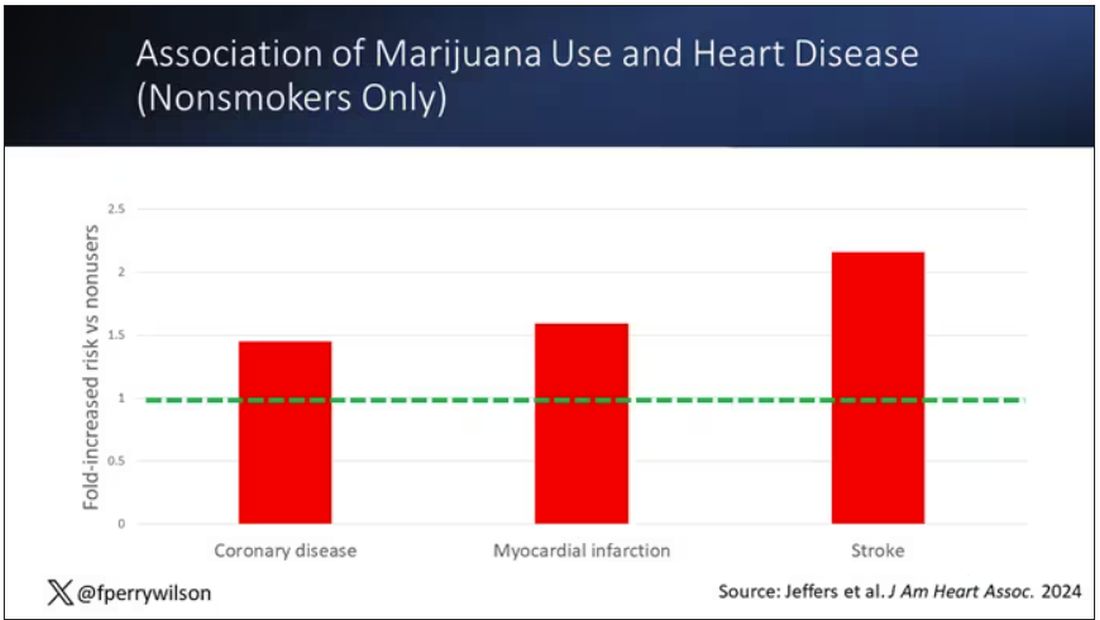

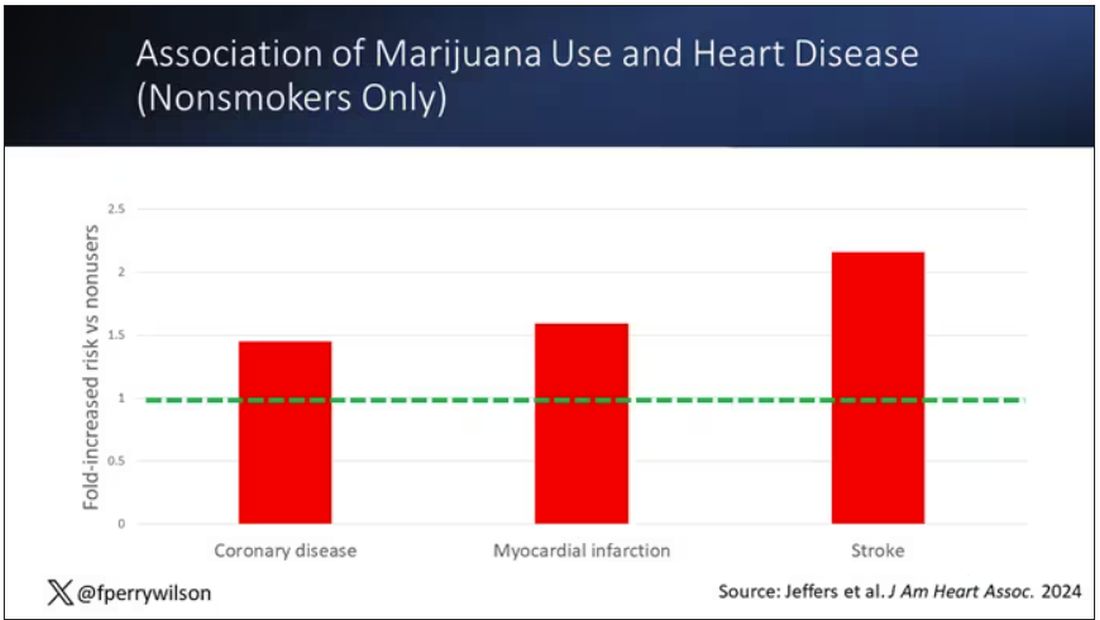

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.

The bigger problem is the fact that this is a cross-sectional design. If you really wanted to know whether marijuana led to heart disease, you’d do a longitudinal study following users and non-users for some number of decades and see who developed heart disease and who didn’t. (For the pedants out there, I suppose you’d actually want to randomize people to use marijuana or not and then see who had a heart attack, but the IRB keeps rejecting my protocol when I submit it.)

Here, though, we literally can’t tell whether people who use marijuana have more heart attacks or whether people who have heart attacks use more marijuana. The authors argue that there are no data that show that people are more likely to use marijuana after a heart attack or stroke, but at the time the survey was conducted, they had already had their heart attack or stroke.

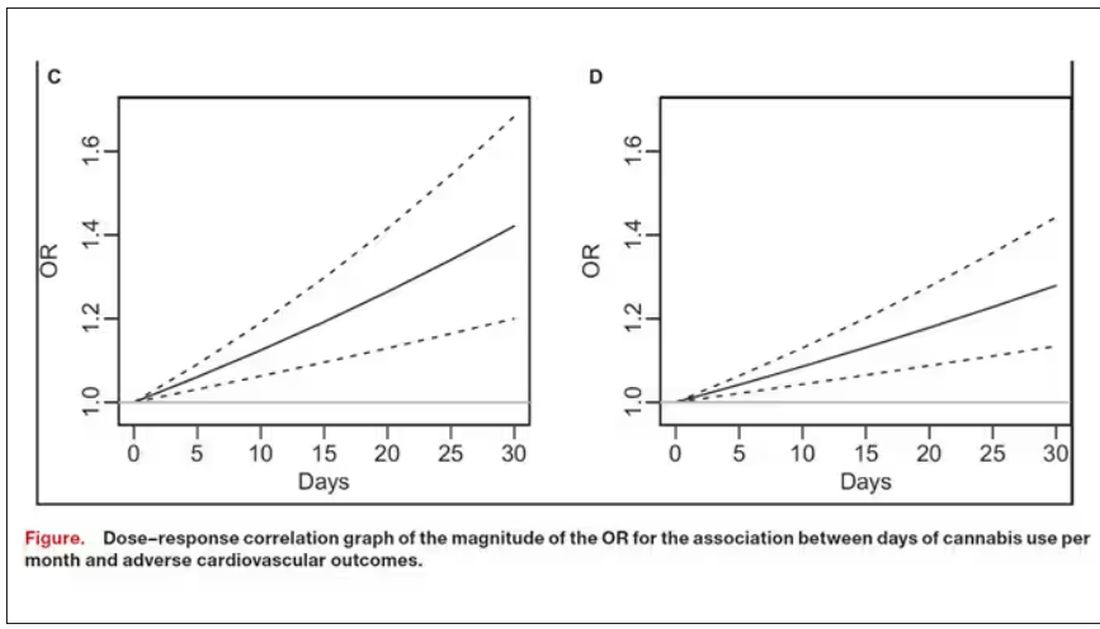

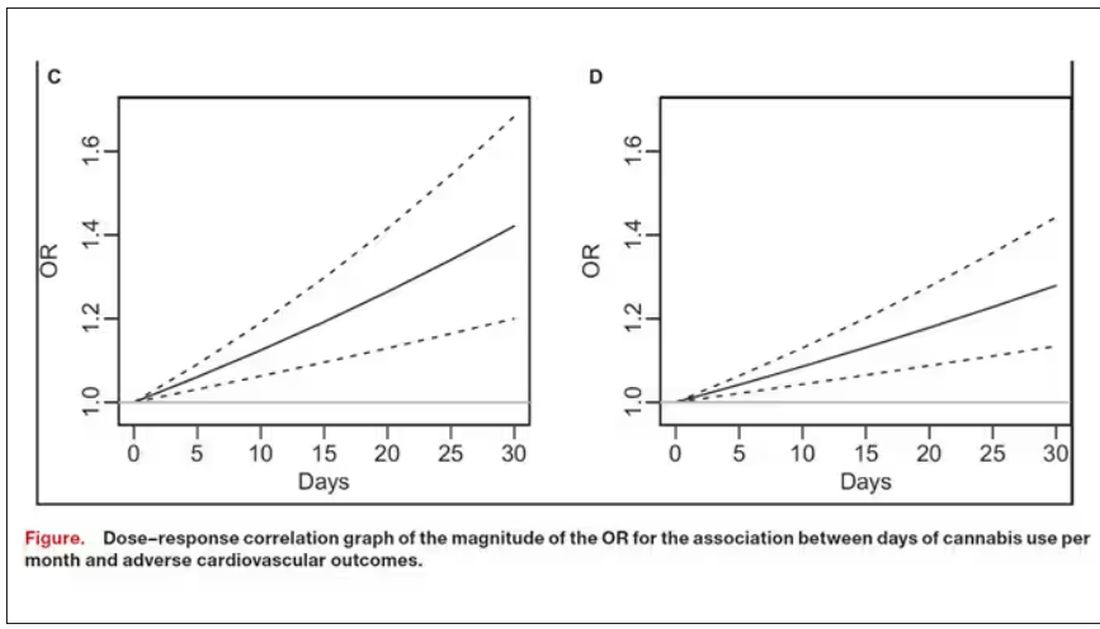

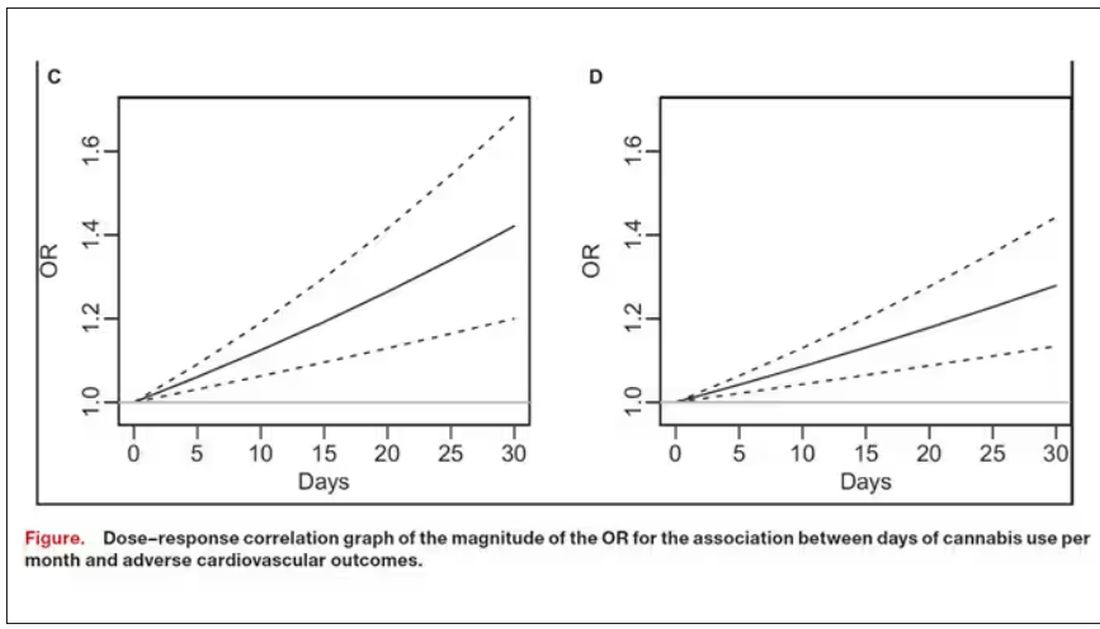

The authors also imply that they found a dose-response relationship between marijuana use and these cardiovascular outcomes. This is an important statement because dose response is one factor that we use to determine whether a risk factor may actually be causative as opposed to just correlative.

But I take issue with the dose-response language here. The model used to make these graphs classifies marijuana use as a single continuous variable ranging from 0 (no days of use in the past 30 days) to 1 (30 days of use in the past 30 days). The model is thus constrained to monotonically increase or decrease with respect to the outcome. To prove a dose response, you have to give the model the option to find something that isn’t a dose response — for example, by classifying marijuana use into discrete, independent categories rather than a single continuous number.

Am I arguing here that marijuana use is good for you? Of course not. Nor am I even arguing that it has no effect on the cardiovascular system. There are endocannabinoid receptors all over your vasculature. But a cross-sectional survey study, while a good start, is not quite the right way to answer the question. So, while the jury is still out, it’s high time for more research.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an epidemiologist trying to explore whether some exposure is a risk factor for a disease, you can run into a tough problem when your exposure of interest is highly correlated with another risk factor for the disease. For decades, this stymied investigations into the link, if any, between marijuana use and cardiovascular disease because, for decades, most people who used marijuana in some way also smoked cigarettes — which is a very clear risk factor for heart disease.

But the times they are a-changing.

Thanks to the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in many states, and even broader social trends, there is now a large population of people who use marijuana but do not use cigarettes. That means we can start to determine whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for heart disease.

And this week, we have the largest study yet to attempt to answer that question, though, as I’ll explain momentarily, the smoke hasn’t entirely cleared yet.

The centerpiece of the study we are discussing this week, “Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults,” which appeared in the Journal of the American Heart Association, is the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1984 that gathers data on all sorts of stuff that we do to ourselves: our drinking habits, our smoking habits, and, more recently, our marijuana habits.

The paper combines annual data from 2016 to 2020 representing 27 states and two US territories for a total sample size of more than 430,000 individuals. The key exposure? Marijuana use, which was coded as the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days. The key outcome? Coronary heart disease, collected through questions such as “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had a heart attack?”

Right away you might detect a couple of problems here. But let me show you the results before we worry about what they mean.

You can see the rates of the major cardiovascular outcomes here, stratified by daily use of marijuana, nondaily use, and no use. Broadly speaking, the risk was highest for daily users, lowest for occasional users, and in the middle for non-users.

Of course, non-users and users are different in lots of other ways; non-users were quite a bit older, for example. Adjusting for all those factors showed that, independent of age, smoking status, the presence of diabetes, and so on, there was an independently increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes in people who used marijuana.

Importantly, 60% of people in this study were never smokers, and the results in that group looked pretty similar to the results overall.

But I said there were a couple of problems, so let’s dig into those a bit.

First, like most survey studies, this one requires honest and accurate reporting from its subjects. There was no verification of heart disease using electronic health records or of marijuana usage based on biosamples. Broadly, miscategorization of exposure and outcomes in surveys tends to bias the results toward the null hypothesis, toward concluding that there is no link between exposure and outcome, so perhaps this is okay.